Peace in a Cup of Tea (Part 2): The Exploitation of the Tribal Tea Plantation Workers in Assam

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 17 Oct 2022

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

“While Enjoying a Cup of Tea, Reflect on Assam’s Tea Gardens, Which Are Rooted in the Abuse and Torture of Labourers Since 1834”[1]

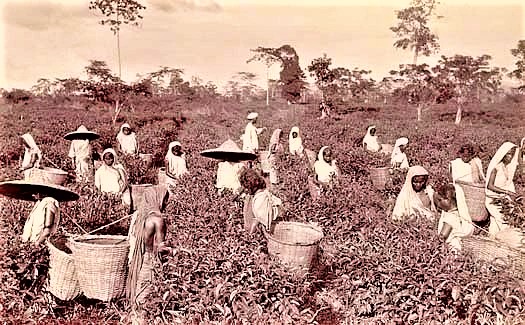

The Exploited Tribal Tea Plantation Workers in Assam in the 19th century India, Under the British Raj.[2]

15 Oct 2022 – This series of publications highlight the history of exploitation of the Tea Workers in the Gardens of Assam beginning in the 19th century with the British colonialist and prevalent to the present-day Assam where Gender Based Violence and exploitation of various types is the order of the day in Bengal and states of Assam in India by progenies of the British “His Maters Voice”

Historically and currently, Assam is the largest tea producing state in India.[3] We all sip tea early in the morning with some biscuits. It’s a part of every Indian household to drink coffee or tea first thing in the morning after brushing our teeth. It’s not just a practice but a cultural inheritance in most parts of the country. It is interesting to realise where all this tea has originated from. There are a large number of tea variants in the market to choose from. Variations in flavor, different types of brands, different compositions of tea, hybrid teas, non tea leaf teas, to confuse customers to buy the right brand of tea powder, tea leaf, tea bag or tea leaf itself, not bagged in specialised paper, in various shapes, ranging from squares, through to circular tea bags, to pyramidal entities. Some are even sealed in foil to increase shelf life and preserve their flavours.

In tea powder alone, there are different combinations like dust tea, tea powder with long leaves, short leaves and other variations. Different flavors have nearly filled the market and some of the notable ones are ginger tea, masala tea, cardamom tea, black tea, organic tea, hibiscus tea, Tulsi tea, lemon tea, iced tea, Oregon tea, and the list ever increasing and endless. Daily, new flavors are added to the range and they are ever evolving. Brands and names associated with tea can be seen in multimillion dollar advertisements on television to lure customers for buying their respective tea powders. Thus, the tea industry is am enormously larege industry and tea plantations can be found in different regions of the the world.[4]

Assam is the first largest producer of tea in India, followed by Darjeeling in west Bengal occupies the second position in generating the largest tea produce for the country. Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka and the north-eastern regions of India are also large tea producing states of the country. However, Assam is the leader in this group and produces almost 52% of the tea in India. An important point to note is that, tea is a favorite beverage in India. Most of the tea produce is consumed within the country itself, however, a significant percentage is exported to other countries. Tea is drunk in various types of cups ranging from small, cheaply mass produced, clay cups, to expensive Royal Albert, fine, bone China cups to designer, Versace cups.

Assam tea is usually associated with black color, hence famously called the black tea. The tea has a taste of malt along with a bright color and strong flavor. These are some of the unique features of the tea grown in this region that differentiate from other tea varieties grown in other parts of the India.[5]

Worldwide, Assam holds the recognition of being the second largest tea producing region in the world. The black tea of Assam first found its roots in the native region of Assam and hence the famous black tea from Assam is famous not only within the country, but is sought after worldwide. These tea gardens were transformed into huge states by the British colonials, when they realised that in these tea producing areas, the soil, as well as the climate were ideal for the growth of tea leaves on a mass scale of production. These early settlers also found the climate cool in sweltering summers, in the hilly regions, far away from the bustling cities of India. River Brahmaputra is the lifeline of the state of Assam and it is the rich basins that provide fertile lands for the cultivation of tea plantations on slopes. The tea plant is grown in the lowlands of Assam, unlike Darjeelings and Nilgiris, which are grown in the highlands. It is cultivated in the valley of the Brahmaputra River, an area of clay soil rich in the nutrients of the floodplain.[6] In addition, the state receives extremely high rainfall, as much as 300 mm, resulting in ideal conditions in the fertile lands for the growth of tea plantations. Furthermore, in summers, the temperatures rise up to as high as 36 degrees Celsius. Thus, on one hand there is good rainfall backed by good humid environments. Together they produce heat on land and this is exactly what makes tea cultivation an ideal occupation in the state of Assam. It is manufactured specifically from the plant[7] Camellia sinensis var. assamica[8] The Assam tea plant is indigenous to Assam. Initial efforts to plant the Chinese varieties in Assam soil did not succeed.[9] Assam tea is now mostly grown at or near sea level and is known for its body, briskness, malty flavour, and strong, bright colour. Assam teas, or blends containing Assam, are often sold as “breakfast” teas. For instance, Irish breakfast tea, a maltier and stronger breakfast tea, consists of small-sized Assam tea leaves.[10]

It is against this background of commercial cultivation on a massive scale, that tribal, female workers are exploited under appalling working conditions and atrocious labour practices from the very beginning of these tea plantations by the British and this exploitation, continues even in the present day, post-independence India, since 1947.

Freshly plucked tea leaves are seen in thehard working hand of a tea garden worker inside Aideobarie Tea Estate in Jorhat in Assam, India. Unrest is brewing among Assam’s so-called Tea Tribes as changing weather patterns upset the economics of the industry. Scientists say climate change is to blame for uneven rainfall that is cutting yields and lifting costs for tea firms. This results in wages not been increased in keeping with inflation and costs of living.

Picture taken April 21, 2015. REUTERS/Ahmad Masood

In the history of modern India, the Renaissance is generally considered a crucial stepping stone that led to the emergence of the modern ‘united India’ nationalism and the subsequent all-India anti-colonial struggle. This period of turmoil marked a transition in values, transformation in social sensibilities and rebirth in cultural creativity.

Its beginning was heralded by the birth of the Brahmo Samaj, the cradle of Bengal Renaissance. This movement was founded by India’s famous polymath-reformer, Raja Rammohan Roy, and its single biggest contribution was the emancipation of women in general and their education in particular.

However, while Roy who is famous for his role in this movement, few people know the story of how another great Brahmo radical of the era exposed the British exploitation of ‘coolies’. This forgotten legend was Dwarkanath Ganguli.[11] A schoolteacher in British-ruled Bengal of the late 19th century, Dwarkanath was born in April 1845 at Magurkhanda village of Bikrampur district. During his days as a student, he was deeply influenced by Akshay Kumar Datta’s thesis on the plight of Indian women that stated: “The first vital step to social regeneration is liberating woman from her bondage.”

While he was still working as a teacher, Dwarkanath started publishing a weekly magazine called Abalabandhab (Friend of Women) through which he began bringing to light concrete cases of exploitation and the extreme suffering of women. As David Kopf (noted historian and professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota) later wrote, “This journal was probably first in the world devoted solely to the liberation of women.” Apart from Abalabandhab, Dwarkanath also raised a storm within the Brahmo Samaj with his radical reformist views that were strongly opposed by the conservative members of the movement. He also served as the headmaster, teacher, maintenance man, guard and sweeper of Hindu Mahila Vidyalaya (that was later renamed Banga Mahila Vidyalaya and subsequently merged with Bethune School). Incidentally, he is also the great-grandfather of legendary Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray.

Passionate about uplifting the underprivileged, he also used his articles to publicise social issues from a humanitarian point of view. He intended to encourage their inclusion on political platforms and to get the government to address the exploitation underlying the issues. The most famous of these efforts were Dwarkanath’s series of explosive articles on the wretched conditions of indentured workers in the tea gardens of Assam. In the 1830s, the British had introduced indentured contracts to recruit cheap and dislocated Indian workforce that would grow lucrative plantation commodities such as tea, coffee, sugar and rubber. Once on plantations, state-enforced penal provisions ensured that they couldn’t leave till their contract expired, no matter the conditions. With time, these workers came to called “coolies”. When a fellow Brahmo member Ram Kumar Vidyaratna, returned from a visit to Assam with dismal tales of opium addiction, inhuman conditions and exploitation of the “coolies” by the British tea planters, Dwarkanath decided to investigate these allegations first-hand. As the white planter-dominated tea industry went to great extents to keep their labour conditions hidden, Dwarkanath knew that exposing this involved great personal risks. But he was undaunted. After an arduous and clandestine journey (that included long treks as the plantation region had neither roads nor vehicles), he finally reached “Planter’s Raj” — as the region was colloquially called, thanks to the absolute dominance of its British managers.

Dwarkanath was shocked to see British managers enjoying the luxuries provided by huge profits while leaving little for the natives as wages and virtually nothing for the development of Assam. What aggrieved him, even more, was the deplorable conditions in which the “coolies” were forced to live. The outraged writer returned to publish a succession of articles in nationalist newspapers, such as KK Mitra’s Sanjibani and Surendranath Banerjee’s Bengalee, to expose the near-slave like conditions of bonded “coolies” in Assam. Soon after, he even took the matter to the forums of the Indian National Congress, with the help of freedom fighter Bipin Chandra Pal. Effectively contesting British claims of worker emancipation, Dwarkanath’s reports told the stories of thousands of Indians who had been lured into Assam’s plantations with the false belief that they would get a living wage in salubrious conditions.

They also grimly described the brutal punishments meted out and how one of every four “coolies” died, their deaths casually dismissed by the planters as being caused by disease or failure to adjust to climatic conditions. While Britain’s influential planter lobby did all they could to prevent Dwarkanath’s reports from having much impact on public opinion, they were unable to prevent it from receiving wide publicity in nationalist circles. In fact, the impact was so great that the Indian National Congress sent its own fact-finding missions to Assam to amass evidence. By the early twentieth century, Dwarkanath’s reports on Assam “coolies” had become an important plank for nationalist agitation against colonial rule. And finally, the pressure proved too much for the British, forcing them to abolish the imperial indenture system in 1920. Today, Dwarkanath’s story has faded away from history textbooks and public memory. A school teacher who took a strong stand against injustice in every form, its time Indian gave this unacknowledged hero the respect and recognition he deserves.[12]

It is reported that Assam’s Tea Gardens flourished on the ‘Abuse and torture’ of their labourers[13] “Our ancestors migrated to these lands from the Orissa-Jharkhand region of present India. We would like to go back and see the villages where we came from.”. These were the words spoken by “Jeremiah”, a tea worker in the Tinkhuria tea estate in upper Assam. We met Jeremiah on our field visit to the tea estate last year. We had the experience of interacting with the workers who have been shedding their sweat in those tea gardens since the last three generations. Some had the longing to go back; some had only stories of their woes to share, of government and plantation managers not listening to their demands. They don’t have properly built schools or hospitals nearby; and often no electricity. They only have deprivation as their asset. One which is passed on from generation to generation ever since they set foot on these lands. Assam is today the largest tea manufacturer in India, contributing significantly to the annual produce which makes India the second largest producer of tea. But this vast empire has been built on the sorrow and sweat of millions of tea labour who had come to these distant land to earn manage a living. This is their story.

Around 1834, tea was discovered in Assam. In the beginning, large amounts of forest clearing and setting up of tea gardens were undertaken by European capitalist planters. The Charter Act of 1833 allowed Europeans to buy land in East India Company colonies. Also, the ‘Wasteland Act’ enabled the Europeans to acquire large swathes of ‘wasteland‘ at concessional rates. Very soon, these ‘wastelands’ were converted to ‘money-yielding-lands’ with the setting up of tea plantations in Upper Assam. The British were keen on ending the Chinese monopoly over tea. Availability of labour always posed a problem for the capitalist. Firstly, they brought in skilled Chinese labourers from Singapore and Penang. But they refused to do work like clearing forests (not mentioned in their contracts). The Chinese soon contracted diseases in this foreign land. Many died and the rest deserted. They turned out to be a headache for the British as they demanded improved conditions for working. By 1860, the Chinese labourers completely disappeared. The British had also recruited Nagas, who were forest dwellers. They were given the work of clearing forests while the Chinese worked in tea plantations. But they were not regular, and the planters were dissatisfied with them.

Meanwhile, the planters also started to recruit ‘Lazy natives’ whom they accused of being inherently lazy owing to their excessive intake of opium. They too turned out to be deserters and were hardly regular. They worked in the tea garden only when they needed money and then left without notice. All this added to the annoyance of British in its inability to find a compliant labour force. Next was the turn of Kachari tribals who had migrated to tea plantations from lower Assam area. Besides most of them leaving just like the local labourers and Chinese, the Kacharis also organised peasant revolt against the British, all the more reasons for the British to be disappointed with the Kacharis.

According to Richu Sanil Chemmalakuzhy[14], after these failed attempts, the British found its rightful labourers in the tribal people of central India.[15] These were “The Industrious Coolies” which fitted in with the British Race Notions. It is interesting to note that, in the first two decades of tea plantations (1840-1860) “…physical coercion and other forms of extra-legal means to control and tame workforce, did not appear to be in practice during this period.” It is because, as Rana P. Behal points out, the management was cautious about the development of tea industry and would not want to jeopardise it at any cost.[16] It was the time when the British were exploiting the regions of Chotanagpur (Central-India). They found the people in these regions more suitable to the work in the tea plantations than Kachari labourers, as they were not the kind “who succumbed to the onslaught of civilisation.“ The British considered them more industrious, diligent and docile. Soon there was significant demand for this tribe in the tea plantation business. All these ‘labour-suitable’ qualities attributed to the men and women of these regions in the colonial discourses, struck a chord with the planters as they decided to import labourers from Central India. This decision decided the lives of millions of men, women and children who migrated, sometimes forcefully or deceived by recruiters or voluntarily owing to pressures, to the ‘Slave Kingdom’ of tea plantations in Upper Assam.[17]

Anxious Tea Plantation labourers in Assam during heavy rains. Picture taken April 21, 2015. REUTERS/Ahmad Masood – RTX1BJH2

A recruitment dilemma materialised very shortly. There was a section of businessmen who took advantage of this persistent need for labour in the Assam gardens. They were the large private contractors who thrived on procuring labour and selling it to the plantations in Assam at “exorbitant” prices. In the expanding phases of the tea industry, they charged the planters Rs. 120 – Rs. 150 per labour, which was quite a significant amount at the time. These intermediaries commercialised labour recruitment. This posed a problem with the British, who were keen on getting labour at cheaper prices. A series of legislations were passed to overcome this problem; thus, the act of 1870 created an alternative system called ‘Garden Sardar’ .

Sardars are non-commercial intermediary agents of the plantations who were sent back to their villages to procure labour from their ‘close kin, community, and caste’. This was a measure intended to bring down the level of deception and coercion employed by the private contractors. Also, buying labourers from the Sardars would be way too cheaper than buying from the contractors. But later on, it was found that the Sardars worked in close alliance with the contractors and were able to exploit the internal vulnerabilities of families in the village. Thus, the contractors and Sardars both emerged as exploitative labour recruiters with the Sardars failed in their purported aim of lowering the irregularities in recruitment.

The British used the system of “Indentured Slavery”, after the abolition of slavery, as it did in the deployment of indentured labourers in South Africa, brought from India, to work on sugarcane plantations in 1860. The cruel subordination under slavery was replaced by a ‘less severe’ indentured labour system in 1833 which has been crucial to the British plantations from then on. Assam Gardens were no exception, where this system was established around 1860. Often this system shared a blurred line with slavery as the coercive methods employed in these gardens were similar to the ones practised under slavery. The indenture system bound the labourers to the plantations through a penal-contract system in which the violators who fled were given harsh punishments by the planters who had been given extra-legal authority. “It was a case of co-existence of an ‘irrational’ and inhuman labour regime producing a modern ‘rational’ corporate world.”

This indentured labour system created a structure of power hierarchy based on coercion and extra-legal authorities. The European planters became an oppressive class and the labourers became the oppressed. There was also a great demographic gap between the Europeans and labourers. The primary purpose of this intimidation was to create a sense of fear among the coolies whose populations outran the Europeans and also keep the labour force obedient. “To preserve their authority, the planters devised the indenture regime to keep their workforce docile, disciplined and intimidated, enforced by legislation from the colonial rule.”

The life of labourers under the sadistic tea planters was harsh and dismal. They got a meagre amount as wage, there was a shortage of food, there were epidemics and diseases. This was complimented by the cruelties meted out to the labourers by their European masters in the form of flogging, making them do extra work, confining them for days without food, humiliating and threatening them with trained dogs that would find those who fled and much more. Their life grew miserable by each passing day as reflected in the high mortality and desertion rate in the plantations across Assam. Figures show out of 84,915 labourers imported between May 1863 and May 1866; only 49, 750 survived, and the rest either perished or managed to escape. People called this the “New Slavery” with the coolies trapped in the predicament of ‘die-if-you-stay’ or ‘die-if-you-go.’ Nothing was done to improve the health and sanitation of the labourers.

The recruiters brought a large number of women and families to the tea plantations. This raised the question of women, who were subservient, abused in every way possible and deprived. The planters used the tactic of bringing the family as this acted as an advantage and bonded the labourer to the gardens. There was also a disparity in treatment of women in the gardens though the work done by both men and women would be the same, with reimbursement being four Indian rupees each month to women and five to the men.

The planters were ‘egalitarian’ in giving punishments. Rapes, flogging, confinement, and other brutalities were committed on the ‘coolie’ women. Women were also victims of deceit at the time of recruitment owing to the thriving flesh trade which was carried out under the smoke pretence of labour mobilisations. As Samita Sen [18]points out, “The buyers of young girls were usually older ‘prostitutes’, who ‘adopted’ and apprenticed them as a source of future income..” All this made the women’s life more pathetic and put them in perilous situations.

The British ‘Justice’ And Indian ‘Injustice’ placed the planters beyond the rule of law and justice evaded the coolies permanently. As the indentured labour system came with ‘blessing’ of extra-legal penal authority for the planters, they used this provision at their liberty. The planters considered it necessary to use flogging and other severe measures to discipline their workforce. As Elizabeth Kolsky [19]argued, “The tea planters demanded protection from law and not protection under law.” The State projected a ‘protector’ image to the coolies, but Kolksy brings to light the real image of the state – protector of the planters. She asks some important questions, “Having authorised the private use of force, could the state subject the planters to prosecution and punishment under the ordinary criminal law?” By flogging someone to death “were they (planters) transgressing or enforcing the colonial order of things?” Could you unlawfully kill a coolie who had no legal status, therefore, it not even amounting to murder?

The tea planters also used force to contain the coolies within the village so that they would not leave the estate to file complaints. Also, the police stations where, in most cases, situated far away from the estates. The European were well connected and influential while the “tea workers were poor, disenfranchised and internally divided along the lines of region and language” . They were illiterate and most often did not even know the procedures of court and other grievance reprisal systems. Even if some case were filed, the Europeans used their influence in higher echelons of Judiciary and administration to get away with light punishment, while the coolies were given severest punishment for the crimes of the same gravity. There were many cases in which planters killed the Estate managers and set them and their bungalows on fire. There were incidents of mob violence and riots. These were considered to be grave ‘injustices’ by the Europeans who turned a blind eye towards the ‘justices’ they meted out to the coolies.

These types of abuses and violations of the women plantation workers, is a global problem, not only recorded in India, or not reported at all, by the workers, for fear of severe repercussions, or even death, but globally. According to report by Alison Maloney and Sophie Jane Evans[20] when tea picker Grace, name changed to protect privacy, refused to have sex with her manager three times, she thought the worst repercussion was going to be having her wages docked. However, horrifyingly a few weeks later, in March 2019, she says he followed her to a remote part of the Malawi plantation where he threw her to the ground and raped her. The anguished cries of the mum-of-two went unheard by her fellow workers, who were too far away to help. Tragically this alleged attack, which left her pregnant and infected with HIV, was one of many reported on the Lejuri Estates, which supplies UK brands including PG Tips and Yorkshire Tea. PGI, the British owners of the Malawi estates, are now facing a law suit over the alleged sexual abuse of workers by a number of supervisors, who are accused of 31 different claims of sexual assault and harassment including ten cases of rape. Marks & Spencer, Tesco, Co-op and Sainsbury’s have stopped using Lujeri to supply their own brand teas while the alleged abuses are investigated and Waitrose is seeking assurances from the company that immediate action is being taken. hey are easy prey to the male supervisors – known as capitaos – with a 2016 Oxfam report claiming sexual exploitation was rife on Malawian plantations, saying “harsh treatment and harassment” was endemic.

The Lejuri workers bringing the lawsuit against PGI claim their wages were docked and contracts were not renewed after managers’ sexual advances were refused, with 18 saying they lost income as a direct result. The capitaos, they claim, would mark them down as absent or having not reached targets, and any time taken off after an attack went unpaid. Six, including Grace, lost their job as a direct result of abuse. The law suit, which names 36 alleged perpetrators highlights “a systemic problem of male workers at plantations abusing their positions of power” to rape, sexually assault, harass and coerce women they supervise into sex.

When Grace told her abuser she was pregnant with his child, “he just laughed”. But the single mother, with two young children, lost her job at five months and tragically gave birth to a stillborn baby in December 2019. Grace said: “People enjoying drinking tea in the UK should know that women working in the fields suffer.”

But the horrific claims are just a tiny snapshot of the wider abuse behind British favourite drink with unsanitary housing, human rights abuses and children being paid as little as 20p a day for hours of back-breaking work in terrible conditions. The British drink 165 million cups of tea a day, and the big six: PG Tips, Twinings, Tetley, Yorkshire, Typhoo, and Clipper – comprise about 70 per cent of the UK market with annual sales of around £500 million. However, the shocking truth behind our daily cuppa leaves a bitter taste.

All this had earned the tea industry the title of ‘Planter’s Raj’. The 20th century was the era of brewing tension, when the labourers Unite! Convinced that the prevailing law is entirely unjust, the labours took the law into their own hands . There were increasing instances of coolie resistance and violence in the tea plantations. The labourers acted collectively with “premeditation, organization and rational inspiration”. They mobbed the Europeans, and in some cases set them on fire along with their bungalows too. There was also tactics of refusal to work collectively that led to violent confrontations leading to many killings of workers as well as planters.

With the rise of nationalism all over the country, there was a widespread protest against the cruel indenture system, spearheaded by Mahatma Gandhi[21] and Charles Freer Andrews[22]. “Nationalist leaders and the Indian press drew frequent attention to the mortality rates and abysmal living arrangements, and slave-like working conditions on the tea gardens.” The penal contract and indentured labour ended in the Assam gardens between 1908 and 1926. As Jayeeta Sharma points out, “Over the years, high mortality and desertion rates coupled with low fertility rates had raised the real cost of labour and reduced its productivity.[23] The state was eventually forced to act to abolish indenture to ensure the long-term viability of the tea sector.”

The Bottom Line, is that the colonials who considered themselves to be racially superior used it to legitimise their violence over the poor labourers on tea plantations in India. These ‘coolies’ were deceived or coerced, beginning from the recruitment process and had to meet with grave injustices at the tea gardens. They were flogged, raped, killed, confined and denied justice at the hands of planters, who made the State dance to their tunes and exploited the labourers further. Even the collective spirit of labourers could not change much.

The spectre of rising peasants continued late into the years after Independence. There were reports of riots and protests. It is rather disheartening to know that “time has stood still in these gardens” as not much has improved here. The colonial legacy, in the form some practices certain practices of hierarchical division which diminish the status of labourers, still is being carried out. For example, “the garden culture” in which the silent servant, who has to hold the tray when guests arrive and carry out their mundane business deals; he cannot even put the tray aside as it is ‘improper‘ to do so. The colonial mindset of the planters and the fate of eternal deprivation of labourers still continues. Marching on to eternity.

While tea may be a simple beverage, it had an enormous impact on the world, at the expense of the tea plantation workers and led, even in the 21st Century, to the problems of exploitation which continues disrupting peace in these peaceful areas of India. The Peace in a Cup of Tea leaves a BITTER TASTE, as exposure of the shocking abuse behind your cup of tea, with kids as young as ten picking tea leaves for 20 pence a day and women tea plantation labourers being beaten and raped. This is apart from being regularly deprived of drinking water and healthcare, while the global community enjoys tea, and the “Tea Lords” thrive on the gains made from human exploitation and gender based violence, on a regular basis in these “Tea Gardens”, of Assam. These are neither gardens, but places akin to a sojourn in the deepest part of living hell, for women, girls and minors.

References:

[1]https://www.huffpost.com/archive/in/entry/how-assams-tea-gardens-are-rooted-in-the-abuse-and-torture-of-l_b_10001090#:~:text=Assam%27s%20Tea%20Gardens%20Are%20Rooted%20In%20The%20Abuse%20And%20Torture%20Of%20Labourers

[2] https://en-media.thebetterindia.com/uploads/2017/11/Assam_TeaPickers01_full.jpg?compress=true&quality=80&w=576&dpr=2.3

[3] https://www.studytoday.net/largest-tea-producing-state-india/#:~:text=Assam%20is%20the%20largest,parts%20of%20the%20country.

[4] https://www.studytoday.net/largest-tea-producing-state-india/#:~:text=Ever%20wondered%20where,of%20the%20country.

[5] https://www.studytoday.net/largest-tea-producing-state-india/#:~:text=Assam%20tea%20is%20usually,parts%20of%20the%20country.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assam_tea#:~:text=The%20tea%20plant%20is%20grown%20in%20the%20lowlands%20of%20Assam%2C%20unlike%20Darjeelings%20and%20Nilgiris%2C%20which%20are%20grown%20in%20the%20highlands.%20It%20is%20cultivated%20in%20the%20valley%20of%20the%20Brahmaputra%20River%2C%20an%20area%20of%20clay%20soil%20rich%20in%20the%20nutrients%20of%20the%20floodplain.

[7] https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=530946

[8] https://web.archive.org/web/20120421021544/http://www.tocklai.net/Activities/tea_class.aspx

[9] Barua, D.N., Dr. (1989). Science and Practice in Tea Culture. TRA Pub. p. 509.

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assam_tea#:~:text=Campbell%2C%20Dawn%20(1995).%20The%20Tea%20Book.%20Pelican%20Publishing.%20p.%C2%A0203.%20ISBN%C2%A09781455612796.

[11] https://www.thebetterindia.com/121647/dwarkanath-ganguli-women-emancipation-coolie-trade-british-india/

[12] https://www.thebetterindia.com/121647/dwarkanath-ganguli-women-emancipation-coolie-trade-british-india/#:~:text=By%20the%20early,recognition%20he%20deserves.

[13] https://www.youthkiawaaz.com/2016/05/slavery-in-assam-tea-gardens-india/#:~:text=How%20Assam%E2%80%99s%20Tea%20Gardens%20Flourished%20On%20The%20%E2%80%98Abuse%20And%20Torture%E2%80%99%20Of%20Their%20Labourers

[14] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=7dc9094b4cc4d959JmltdHM9MTY2NTcwNTYwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE0OA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=Richu+Sanil+Chemmalakuzhy&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cueW91dGhraWF3YWF6LmNvbS8yMDE2LzA1L2ltcGFjdC1vZi1hZHZlcnRpc2VtZW50cy1vbi1zdWJjb25zY2lvdXMv&ntb=1

[15] https://www.youthkiawaaz.com/2016/05/slavery-in-assam-tea-gardens-india/

[16] https://www.youthkiawaaz.com/2016/05/slavery-in-assam-tea-gardens-india/#:~:text=The%20Industrious%20Coolies,at%20any%20cost.

[17] https://www.youthkiawaaz.com/2016/05/slavery-in-assam-tea-gardens-india/#:~:text=It%20was%20the,in%20Upper%20Assam.

[18] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=9474eabcbf8f4441JmltdHM9MTY2NTcwNTYwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTQxOQ&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=Samita+Sen&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvU2FtaXRhX1NlbiM6fjp0ZXh0PVNhbWl0YSUyMFNlbiUyMGlzJTIwYW4lMjBJbmRpYW4lMjBoaXN0b3JpYW4lMjBhbmQlMjBhY2FkZW1pYy4sSGlzdG9yeSUyMGF0JTIwdGhlJTIwVW5pdmVyc2l0eSUyMG9mJTIwQ2FtYnJpZGdlJTIwc2luY2UlMjAyMDE4Lg&ntb=1

[19] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=323fda4cfc3a042cJmltdHM9MTY2NTcwNTYwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTIxOA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=Elizabeth+Kolsky&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuY2FtYnJpZGdlLm9yZy9jb3JlL2pvdXJuYWxzL2pvdXJuYWwtb2YtYnJpdGlzaC1zdHVkaWVzL2FydGljbGUvZWxpemFiZXRoLWtvbHNreS1jb2xvbmlhbC1qdXN0aWNlLWluLWJyaXRpc2gtaW5kaWEtd2hpdGUtdmlvbGVuY2UtYW5kLXRoZS1ydWxlLW9mLWxhdy1jYW1icmlkZ2Utc3R1ZGllcy1pbi1pbmRpYW4taGlzdG9yeS1hbmQtc29jaWV0eS1jYW1icmlkZ2UtY2FtYnJpZGdlLXVuaXZlcnNpdHktcHJlc3MtMjAxMC1wcC0yNTItOTUwMC1jbG90aC80MzEyRjM3Q0I2NkI0MjVERDE3M0EwRDdBMzNBQjM5OQ&ntb=1

[20] https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/14479682/abuse-tea-child-labour-rape-slavery/

[21] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=e091b96dcde3439fJmltdHM9MTY2NTcwNTYwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTIwOQ&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=gandhi+mahatma&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvTWFoYXRtYV9HYW5kaGk&ntb=1

[22] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=887008e93346ad9eJmltdHM9MTY2NTcwNTYwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE5OQ&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=C.F.+Andrews&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvQ2hhcmxlc19GcmVlcl9BbmRyZXdz&ntb=1

[23] https://www.youthkiawaaz.com/2016/05/slavery-in-assam-tea-gardens-india/#:~:text=The%20spectre%20of,fate%20of%20eternal

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: British Colonialism, British empire, Colonization, English Colonialism, Exploitation, India, Racism, Slave labor

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 17 Oct 2022.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Peace in a Cup of Tea (Part 2): The Exploitation of the Tribal Tea Plantation Workers in Assam, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.