Peace Disruptors–The Conversion and Repurposing of Places of Worship (Part 1): The Great Mosque at Cordoba

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 14 Nov 2022

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

“Religion has been the main cause of Peace Disruption through the centuries.”[1]

12 Nov 2022 – This Part 1 in the series of publications on conversions of existing places of worship into buildings for the remembrance and supplication of God of other religions, following a conquest, highlights the emergence of numerous cathedrals-mosques, demonstrating an interesting fusion of not only Islamo-Gothic architecture, but also syncretism of the age-old traditions, as well as culture of the residents of the area, globally.

These architectural conversions, of places of worship, have taken place in Europe, especially in the Andalusia region of Spain, initially occupied by Christian Kings, who built magnificent cathedrals. then the Islamic invasion of these cities, where grand mosques of unimaginable opulence were constructed, and finally following a reconquest of the Islamic governed cities by the Catholic Kings and Queen of Spain, the grandeur of the Islamic Mosques, were converted into huge cathedrals. Similar “Peace Disruptors” were abound in Constantinople, the former capital of the Eastern Byzantine Empire, presently, Istanbul. Such conversions took place also in India with the Sultanate and Mughal invasions of the predominantly Hindu country, resulted in destruction of temples, as well as mosques, depending who is in power.

This recurrent tragedy of Peace Disruption, is the ongoing cause of inter religious sectarianism, even today, globally as well as in the Indian Peninsula. This has caused the massacres of millions of ordinary citizens over the centuries, the dismantling of glorious empires and kingdoms as well as destruction of superb architectural and religiously significant massive temples, mosques, synagogues, cathedrals and other religious places of worship, where the remembrance of God, occurs on a daily basis, no matter which religious community the physical structure belongs to, designating a certain religion.

The peace disruption originates from various sources. When the author visited the museum city of Toledo in Spain, the tour took him to the ancient Toledo Cathedral. The La Catedral Primada Santa María de Toledo, Primate Cathedral of Saint Mary of Toledo, also known as ‘Dives Toletana’, the Rich Toledan), is considered to be the most spectacular piece of Islamo-Spanish-Gothic architecture, and one of the most important examples of High Gothic structures in Spain. It is located in the heart of the city of Toledo, which as of 1986 is considered by the UNESCO a World Heritage Site. Apart from its architectonic value, it contains several works of art by Baroque painter, El Greco, and a notable Baroque high altarpiece. Many other fine artworks can be visited at the cathedral.

This cathedral is a place of unique historic relevance, and nearly every detail within it, including the treasures, artwork, sculptures, woodwork, and other religious artefacts is exquisitely built. The cathedral is unanimously considered the magnum opus of High Gothic style in Spain. Construction began in 1226 and went on for more than 250 years, it was built over the remains of a Visigothic church which was later used as a mosque. The Gothic style was tastefully combined with Mudéjar elements, an Arab style developed by Muslims who stayed in Spain after the Spanish Reconquista. This trait makes the cathedral a one-of-a-kind building. This architecture is a clear example of syncretism. The Gothic features of the cathedral have a clear French influence. It consists of five naves, held by 88 columns. The construction was begun by Maestro Martin and ended in 1493 when the last vault was finally concluded. The altarpiece, upper choir, and fencing were constructed in the 16th century.

Primate Cathedral of Saint Mary of Toledo in Spain[3]. Note the Islamic architecture fused with the Gothic Spire.

The tower features both a Gothic and an Islamic, Mudéjar style, as the rest of the cathedral. It sits in the Northwest corner of the church. It is made up of five levels. The second level used to serve as a residence for the Ringer and the third level was used as a prison. The tower can be visited and climbed during the church’s visiting hours. It is from the third level prison, where the arrested, Moors, the Islamic prisoners were taken out after the main Sunday service in the church and heard toward the side roof of the main nave, for slow executions, upon the specific orders of King Ferdinand II[4] and Queen Isabella I[5] the ruler of the two kingdoms of Spain and Aragon, the powerful Catholic monarchy in the 15th century, when they regained the city, lost to the Moors from North Africa. According to the tour guide, the fresh batch of Islamic prisoners were manacled to the 45o sloping roof.

The rusted iron manacles can still be seen fastened to the side of the roof. The prisoners were then left to slowly become dehydrated and expire over the next few days, in the scorching summer heat, or freezing winter conditions, experienced in the region. Some, hardy Moors took a week to die, upon which the regional vultures, first feasted on their eyeballs, as a delicacy and then the rest of the flesh. Eventually, the bony elements slid off the roof, following heavy rains, into a deep trough on the side of the building and mixed with the elements, therein, fulfilling the prophesy of Jehovah: “Dust to Dust and Ashes to Ashes”. Such were the atrocities committed at the time. outside this, very Cathedral, visited by thousands of tourists, as the centerpiece of Toledo.

The cathedral of Toledo is one of the three 13th century, High Gothic cathedrals in Spain and is considered, in the opinion of some authorities, to be the magnum opus[6] of the Gothic style in Spain. It was begun in 1226 under the rule of Ferdinand III, and the last Gothic contributions were made in the 15th century when, in 1493, the vaults of the central nave were finished during the time of the Catholic Monarchs. It was modeled after the Bourges Cathedral, although its five naves plan is a consequence of the constructors’ intention to cover all of the sacred space of the former city mosque with the cathedral, and of the former sahn with the cloister. It also combines some characteristics of the Mudéjar style, mainly in the cloister, with the presence of multifoiled arches in the triforium. The spectacular incorporation of light and the structural achievements of the ambulatory vaults are some of its more remarkable aspects. It is built with white limestone from the quarries of Olihuelas, near Toledo.

The city had been the episcopal seat of Visigothic Spain. The numerous Councils of Toledo attest to its important ecclesiastical past. Also, the abjuration of Arianism on the part of Reccared occurred there. The Muslim invasion did not immediately eliminate the Christian presence and the bishopric remained established in the church of Saint Mary of Alfizén.

The Visigothic church was demolished and the main mosque of the city of Toledo was erected in its place. Some investigators point out that the prayer hall of the mosque corresponds with the layout of the five naves of the current cathedral; the sahn would coincide with part of the current cloister and the chapel of Saint Peter and the minaret with the bell tower. Using certain archeological data it is possible to discern an Islamic column mounted inside the chapel of Saint Lucy; the marble shafts that decorate the exterior of the choir are an improvement of an old Muslim construction, and the intertwined arches of caliphate style in the triforium of the main chapel and of the ambulatory coincide with the Muslim construction tradition of Cordova.

The city of Toledo was reconquered by Alfonso VI, King of León and Castile, in 1085. One of the points of the Muslim capitulation that made possible the transfer of the city without bloodshed was the king’s promise to conserve and respect their institutions of higher learning, as well as the customs and religion of the Muslim population which had coexisted with the larger Mozarabic population. Naturally, the preservation of the main mosque was integral to this compromise. Shortly thereafter, the king had to depart on matters of state, leaving the city in charge of his wife Constance and the abbot of the monastery of Sahagún, Bernard of Sedirac (or Bernard of Cluny), who had been elevated to the rank of archbishop of Toledo. These two, in mutual accord and taking advantage of the absence of the king, undertook an unfortunate action which, as told by the priest Mariana in his General History of Spain, almost provoked a Muslim uprising and consequent ruin of the recently conquered city.

On 25th October 1087, the archbishop in cooperation with Queen Constance sent an armed contingent to seize the mosque by force. They proceeded to install a provisional altar and hung a bell in the minaret, following Christian custom to ‘cast out the filthiness of the law of Mohammed’.[7] The priest Mariana writes that king Alfonso VI was so irritated by these events that neither the archbishop nor the queen were able to prevent him from ordering the execution of all the active participants. Legend tells that the local Muslim populace itself helped restore peace, with its chief negotiator, faqih Abu Walid, requesting the king to show mercy, and imploring his fellow townsmen to accept the Christian usurpation as legitimate. In gratitude for this gesture, the Cathedral Chapter dedicated a homage to Walid and ordered his effigy to be placed on one of the pillars in the main chapel, in this way perpetuating his memory.[8] Thus the conversion of the Toledan mosque was upheld and it remained consecrated as a Christian cathedral.

The building plans of the former mosque have not been preserved, nor is the appearance of the structure known, but considering the preserved vestiges of mosques in other Spanish cities; Seville, Jaén, Granada, Málaga, and including the Mosque of Cordova, it may be supposed that it was a columnary building, with horseshoe arcades based on Islamic architecture, on top of columns in revision of earlier Roman and Visigothic construction. It is possible that it appeared very much like the Church of the Savior of Toledo, previously a mosque.

King Alfonso VI made important donations to the new church. On 18th December 1086, the cathedral was placed under the advocacy of María and it was granted villas, hamlets, mills and one third of the revenues of all the rest of the churches of the city. The first royal privilege that is preserved is a prayer in Latin, beginning: I, Alfonsus, Emperor of Hesperia by the disposition of God, grant to the metropolitan See, that is, the church of Saint Mary in the city of Toledo, the complete honour that she should have the pontifical see according to what before was constituted by the holy fathers…[9]

The Cathedral of Toledo was built much later than the Grand Mosque of Cordova. The Great Mosque was built in the context of the new Umayyad Emirate in Al-Andalus which Abd ar-Rahman I founded in 756. Abd ar-Rahman was a fugitive and one of the last remaining members of the Umayyad royal family, which had previously ruled the first hereditary caliphate based in Damascus, Syria. This Umayyad Caliphate was overthrown during the Abbasid Revolution in 750 and the ruling family were nearly all killed or executed in the process. Abd ar-Rahman survived by fleeing to North Africa and, after securing political and military support, took control of the Muslim administration in the Iberian Peninsula from its governor, Yusuf ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri. Cordoba was already the capital of the Muslim province and Abd ar-Rahman continued to use it as the capital of his independent emirate.[10],[11]

Construction of the mosque began in 785–786 (169 AH) and finished a year later in 786–787 (170 AH).[12] This relatively short period of construction was aided by the reuse of existing Roman and Visigothic materials in the area, especially columns and capitals.[13]: 40 Syrian (Umayyad), Visigothic, and Roman influences have been noted in the building’s design, but the architect is not known. The craftsmen working on the project probably included local Iberians as well as people of Syrian origin. According to tradition and historical written sources, Abd ar-Rahman involved himself personally and heavily in the project, but the extent of his personal influence in the mosque’s design is debated.[14]

The Great Mosque of Córdoba held a place of importance amongst the Islamic community of al-Andalus for centuries. In Córdoba, the Umayyad capital, the Mosque was seen as the heart and central focus of the city.[15] Muhammad Iqbal described its interior as having “countless pillars like rows of palm trees in the oases of Syria”.[16] To the people of al-Andalus “the beauty of the mosque was so dazzling that it defied any description.”[17],[18]

After all of its historical expansions, the mosque-cathedral covers an area of 590 by 425 feet (180 m × 130 m).[19] The building’s original floor plan follows the overall form of some of the earliest mosques built from the very beginning of Islam.[20] Some of its features had precedents in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, which was an important model built before it.[21] It had a rectangular prayer hall with aisles arranged perpendicular to the qibla, the Kaaba in Mecca, the direction towards which Muslims pray.[22] It has thick outer walls with a somewhat fortress-like appearance. To the north is a spacious courtyard (the former sahn), surrounded by an arcaded gallery, with gates on the north, west, and east sides, and fountains that replace the former mosque fountains used for ablutions. A bridge or elevated passage (the sabat) once existed on the west side of the mosque which connected the prayer hall directly with the Caliph’s palace across the street.[23] Al-Razi, an Arab writer, speaks of the valuable wine-coloured marble, obtained from the mountains of the district, which was much used in embellishing the naves of the mosque.

The Christian-era additions (after 1236) included many small chapels throughout the building and various relatively cosmetic changes. The most substantial and visible additions are the cruciform nave and transept of the Capilla Mayor, the main chapel where Mass is held today, which were begun in the 16th century and inserted into the middle of the former mosque’s prayer hall, as well as the remodelling of the former minaret into a Renaissance-style bell tower.[24]

The mosque-cathedral’s hypostyle hall dates from the original mosque construction and originally served as its main prayer space for Muslims. The main hall of the mosque was used for a variety of purposes. It served as a central prayer hall for personal devotion, for the five daily Muslim prayers and the special Friday prayers accompanied by a sermon. It also would have served as a hall for teaching and for Sharia law cases during the rule of Abd al-Rahman I and his successors.[25]

The hall was large and flat, with timber ceilings held up by rows of double-tiered arches (arcades) resting on columns.[26] These rows of arches divided the original building into 11 aisles or “naves” running from north to south, later increased to 19 by Al-Mansur’s expansion, while in turn forming perpendicular aisles running east–west between the columns.[27] The approximately 850 columns were made of jasper, onyx, marble, granite and porphyry.[2] In the original mosque, all of the columns and capitals were reused from earlier Roman and Visigothic buildings, but subsequent expansions, starting with Abd al-Rahman II, saw the incorporation of new Moorish-made capitals that evolved from earlier Roman models.[13]: 44–45 [14]: 14 [91] The nave that leads to the mihrab – which was originally the central nave of the mosque until Al-Mansur’s lateral expansion of the building altered its symmetry – is slightly wider than the other naves, demonstrating a subtle hierarchy in the mosque’s floor plan.[13]: 40 [16]: 20

The double-tiered arches were an innovation that permitted higher ceilings than would otherwise be possible with relatively low columns. They consist of a lower tier of horseshoe arches and an upper tier of semi-circular arches.[16]: 20 The voussoirs of the arches alternate between red brick and white stone. Colour alternations like this were common in Umayyad architecture in the Levant and in pre-Islamic architecture on the Iberian Peninsula.[13]: 42 According to Anwar G. Chejne, the arches were inspired by those in the Dome of the Rock.[28] Horseshoe arches were known in the Iberian Peninsula in the Visigothic period (e.g. the 7th-century Church of San Juan de Baños), and to a lesser extent in Byzantine and Umayyad regions of the Middle East; however, the traditional “Moorish” arch developed into its own distinctive and slightly more sophisticated version.

The mosque’s architectural system of repeating double-tiered arches, with otherwise little surface decoration, is considered one of its most innovative characteristics and has been the subject of much commentary.[29] The hypostyle hall has been variously described as resembling a “forest of columns”[30] and having an effect similar to a “hall of mirrors”.[31] Scholar Jerrilynn Dodds has further summarized the visual effect of the hypostyle hall with the following:[32]

“Interest in the mosque’s interior is created, then, not by the application of a skin of decoration to a separately conceived building but by the transformation of the morphemes of the architecture itself: the arches and voussoirs. Because we share the belief that architectural components must by definition behave logically, their conversion into agents of chaos fuels a basic subversion of our expectations concerning the nature of architecture. The tensions that grow from these subverted expectations create an intellectual dialogue between building and viewer that will characterize the evolving design of the Great Mosque of Cordoba for over two hundred years.”

The mosque’s original flat wooden ceiling was made of wooden planks and beams with carved and painted decoration.[33] Preserved fragments of the original ceiling, some of which are now on display in the Courtyard of the Oranges, were discovered in the 19th century and have allowed modern restorers to reconstruct the ceilings of some of the western sections of the mosque according to their original style.[34] The eastern naves of the hall, in al-Mansur’s expansion, by contrast, are now covered by high Gothic vaults which were added in the 16th century by Hernan Ruiz I.[35] On the exterior, the building has gabled roofs covered in tiles.

The prayer hall also has a richly-decorated mihrab, an enclave symbolising the direction of prayer for all Muslims, surrounded by an architecturally-defined maqsura, an area reserved for the emir or caliph during prayer, which dates from the expansion of Caliph Al-Hakam II after 965. This maqsura area covers three bays along the southern qibla wall in front of the mihrab, and was marked off from the rest of the mosque by an elaborate screen of intersecting horseshoe and polylobed arches; a feature which would go on to be highly influential in the subsequent development of Moorish architecture.[36]

The mihrab opens in the wall at the middle of this maqsura, while two doors flank it on either side. The door on the right, Bab al-Sabat (“door of the sabat”), gave access to a passage which originally led to the sabat, an elevated passage over the street which connected the mosque to the caliph’s palace. The door on the left, Bab Bayt al-Mal (“door of the treasury”), led to a treasury located behind the qibla wall, presently, partly occupied by the cathedral’s treasury.

The mihrab consists of a horseshoe arch leading to a small heptagonal chamber covered by a shell-shaped cupola above a ring of polylobed blind arches and carvings. This is the earliest known mihrab that consists of an actual room rather than just a niche in the wall. Under the horseshoe arch are two pairs of short marble columns with capitals, each pair featuring one red column and one dark green column, which are believed to have been reused from the mihrab of Abd al-Rahman II’s earlier expansion of the mosque.[37] The mihrab is, in turn, surrounded by a typical arrangement of radiating arch decoration and a rectangular framing or alfiz, which is also seen in the design of the earlier western mosque gate of Bab al-Wuzara, the Puerta de San Esteban today and was likely also present in the design of the mosque’s first mihrab.[38]

Above this alfiz is another decorative blind arcade of polylobed arches. The lower walls on either side of the mihrab are panelled with marble carved with intricate arabesque vegetal motifs, while the spandrels above the arch are likewise filled with carved arabesques. The voussoirs of the arch, however, as well as the rectangular alfiz frame and the blind arcade above it, are all filled with gold and glass mosaics. Those in the voussoirs and the blind arcade form vegetal and floral motifs, while those in the alfiz and in smaller bands at the springs of the arch contain Arabic inscriptions in Kufic script. The two doors on either side of the mihrab section are also framed by similar, but less elaborate, mosaic decoration.

The three bays of the maqsura area (the space in front of the mihrab and the spaces in front of the two side doors) are each covered by ornate ribbed domes. The use of intersecting arches in this area also solved the problem of creating additional support to bear the weight and thrust of these domes. The domes themselves are built with eight intersecting stone ribs. Rather than meeting in the center of the dome, the ribs intersect one another off-center, forming an eight-pointed star with an octagonal “scalloped” cupola in the center. The middle dome, in front of the mihrab, is especially elaborate and is also covered by mosaic decoration, including an inscription around the base of the central cupola containing verses from the Qur’an (Surah 22: 77–78).[39] The translation reads:

O ye who believe! Bow down, prostrate yourselves, and adore your Lord; and do good; that ye may prosper. And strive in His cause as ye ought to strive, (with sincerity and under discipline). He has chosen you, and has imposed no difficulties on you in religion; it is the culture of your father Abraham. It is He Who has named you Muslims, both before and in this (Revelation); that the Apostle may be a witness for you, and ye be witnesses for mankind![40]

Scholars have affirmed that the style of the mosaics in this part of the mosque is heavily influenced by Byzantine mosaics, which corroborates historical accounts of the Caliph requesting expert mosaicists from the Byzantine emperor at the time, who agreed and sent him a master craftsman.[41] Scholars have argued that this use of Byzantine mosaics is also part of a general desire – whether conscious or not – by the Cordoban Umayyads to evoke connections to the early Umayyad Caliphate in the Middle East, in particular to the Great Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, where Byzantine mosaics were a prominent element of the decoration.[42]

The Arabic inscriptions in the mihrab’s mosaics are the first example of a major series of political-religious inscriptions inserted into Umayyad Andalusi architecture. They contain selected excerpts from the Qur’an as well as foundation inscriptions praising the patron (Caliph Al-Hakam II) and the people who assisted in the construction project.[43] The largest inscription of the alfiz (rectangular frame) around the mihrab, in gold Kufic characters on a dark background, begins with two excerpts from the Qur’an (Surah 32:6 and Surah 40:65), translated as:

Such is He, the Knower of all things, hidden and open, the Exalted, the Merciful. He is the Living, there is no God but He; call upon Him, giving Him sincere devotion, praise be to God the Lord of the worlds.

This is followed by a text commemorating al-Hakam’s expansion:

Thanks be to God Lord of the worlds who chose the Imam al-Mustansir Billah, ‘Abd allah al-Hakam amir al-mu’minin, may God preserve him in righteousness, for this venerable construction and who was his aid in [effecting] his eternal structure, for the goal of making it more spacious for his followers…in fulfillment of his and their wishes, and as an expression of his grace them.[44]

Immediately inside this rectangular inscription frame is another inscription in a horizontal band above the mihrab, in dark letters against a gold background, which quotes Surah 59:23, translated as:

God is He, than Whom there is no other god. The Sovereign, the Holy One, the Source of Peace (and Perfection), the Guardian of Faith; the Preserver of Safety, the Exalted in Might, the Irresistible, the Supreme. Glory be to God! (High is He) above the partners they attribute to Him.[45]

Nuha N. N. Khoury, a scholar of Islamic architecture, has interpreted these inscriptions, in combination with the other foundation inscriptions in this part of the mosque, as an attempt to present the mosque as a “universal Islamic shrine”, similar to the mosques of Mecca and Medina, and to portray Caliph al-Hakam II as the instrument through which God built this shrine. This framed the official history of the Umayyad dynasty in prophetic terms, promoting the idea of the new Umayyad caliphs in Cordoba as having a universal prerogative in the Islamic world.[46]

In the nave or aisle of the hypostyle hall which leads to the mihrab, at the spot which marks the beginning of Al-Hakam’s 10th century extension, is a monumental ribbed dome with ornate decoration. The ribs of this dome have a different configuration than those of the domes in front of the mihrab. Their intersection creates a square space in the center with an octagonal scalloped cupola added over this. In total, this intersection of ribs creates 17 vaulted compartments of square or triangular shape, in different sizes, each further decorated with a variety of miniature ribbed domes, star-shaped mini-domes, and scalloped shapes. The space under this dome was surrounded on three sides by elaborate screens of interlacing arches, similar to those of the maqsura but even more intricate.

This architectural ensemble apparently marked the transition from the old mosque to Al-Hakam II’s expansion, which some scholars see as having a status similar to a “mosque-within-a-mosque”.[47] The dome is now part of the Villaviciosa Chapel, while two of the three intersecting arch screens are still present, the western one has disappeared and been replaced by the 15th century Gothic nave added to the chapel. Like the ornate decorative arches, this dome and the other ribbed domes of the maqsura were highly influential in subsequent Moorish architecture of the period, appearing also in simpler but imaginative forms in the small Bab al-Mardum Mosque in Toledo and giving rise to other ornamental derivations like the much later stucco domes of the Great Mosque of Tlemcen and the Great Mosque of Taza.[48]

The courtyard is known today as the Patio de los Naranjos or “Courtyard of the Orange Trees”.[49] Until the 11th century, the mosque courtyard (also known as a sahn) was unpaved earth with citrus and palm trees irrigated at first by rainwater cisterns and later by aqueduct. Excavation indicates the trees were planted in a pattern, with surface irrigation channels. The stone channels visible today are not original.[50] As in most mosque courtyards, it had fountains or water basins to help Muslims perform ritual ablutions before prayer. The arches that marked the transition from the courtyard to the interior of the prayer hall were originally open and allowed natural light to penetrate the interior, but most of these arches were walled up during the Christian period (after 1236) as chapels were built along the northern edge of the hall.[51]

The courtyard of the original mosque of Abd ar-Rahman I had no surrounding gallery or portico, but it is believed that one was added by Abd ar-Rahman III between 951 and 958.[52] The current gallery, however, was rebuilt with a similar design by architect Hernán Ruiz I under Bishop Martín Fernández de Angulo between 1510 and 1516.[53]The current layout of the gardens and trees is the result of work carried out under Bishop Francisco Reinoso between 1597 and 1601. Today the courtyard is planted with rows of orange trees, cypresses, and palm trees.[54]

Abd al-Rahman III added the mosque’s first minaret, tower used by the muezzin for the call to prayer, in the mid-10th century. The minaret has since disappeared after it was partly demolished and encased in the Renaissance bell tower that is visible today, which was designed by Hernán Ruiz III and built between 1593 and 1617.[55] The minaret’s original appearance, however, was reconstructed by modern Spanish scholar Félix Hernández Giménez with the help archeological evidence as well as historical texts and representations. For example, the two coat-of-arms on the present-day cathedral’s Puerta de Santa Catalina depict the tower as it appeared before its later reconstruction.[56]

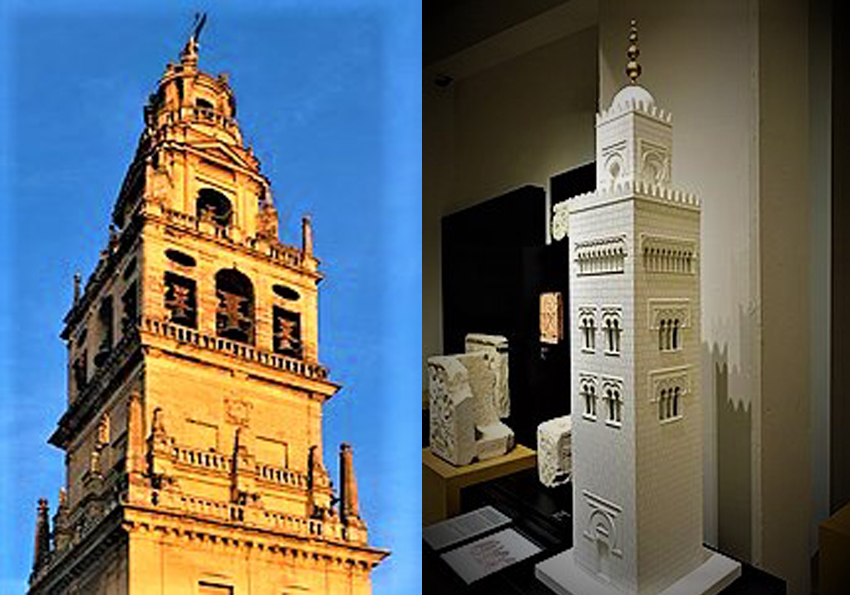

The Mosque-Cathedral at Cordoba: The Present and the Past. The Ringing of the Bells or the Call of the Muezzin, both calling the Devotees to pray to God.

Left: The Cathedral at Cordoba Belfry Tower

Right: Model of the reconstructed minaret of Abd ar-Rahman III at the

Archeological Museum of Cordoba

The original minaret was 47 meters high and had a square base measuring 8.5 meters per side.[57] Like other Andalusi and North African minarets after it, it was composed of main shaft and a smaller secondary tower or “lantern”, also with a square base) which surmounted it. The lantern tower was in turn surmounted by a dome and topped by a finial in the shape of a metal rod with two golden spheres and one silver sphere, often referred to as “apples”, decreasing in size towards the top. The main tower contained two staircases, which were built for the separate ascent and descent of the tower. About half-way up, the stairways were lit by sets of horseshoe-arch windows whose arches were decorated with voussoirs of alternating colours which were in turn surrounded by a rectangular alfiz frame, similar to the decoration seen around the arches of the mosque’s outer gates.

On two of the tower’s façades there were three of these windows side by side, while on the two other façades the windows were arranged in two pairs. These double pairs or triplets of windows were repeated on the level above. Above these, just below the summit of the main shaft on each façade, was a row of nine smaller windows of equivalent shape and decoration. The top edge of the main shaft was crowned with a balustrade of sawtooth-shaped merlons, similar to those commonly found in Morocco. The lantern tower was decorated by another horseshoe archway on each of its four facades, again featuring an arch of alternating voussoirs framed within an alfiz.[58]

Construction of a new cathedral bell tower to encase the old minaret began in 1593[59] and, after some delays, was finished in 1617.[60] It was designed by architect Hernan Ruiz III, the grandson of Hernan Ruiz I, who built the tower up to the bells level but died before its completion. His plans were followed by Juan Sequero de Matilla who finished the tower after him. The bell tower is 54 meters tall and is the tallest structure in the city. It consists of a solid square shaft up the level of the bells, where serliana-style openings feature on all four sides. Above this is a lantern structure which in turn is surmounted by a cupola. The dome at the summit is topped by a sculpture of Saint Raphael which was added in 1664 by architect Gaspar de la Peña, who had been hired to perform other repairs and fix structural problems. The sculpture was made by Pedro de la Paz and Bernabé Gómez del Río.[61] Next to the base of the tower is the Puerta del Perdón (“Door of Forgiveness”), one of the two northern gates of the building.[62]

The Grand Mosque was converted into a Christian cathedral in the 13th century. The original structure was built by the Umayyad ruler ʿAbd ar-Raḥmān I in 784–786. The groundbreaking was in 795. with extensions in the 9th and 10th centuries that doubled its size, ultimately making it one of the largest sacred buildings in the Islamic world. Since 1236 the former mosque has served as a Christian cathedral, and its Moorish character was altered in the 16th century with the erection in the interior of a central high altar and cruciform choir, numerous chapels along the sides of the vast quadrangle, and a belfry 300 feet (90 metres) high in place of the old minaret. The mosque was converted to a cathedral in 1236 when Córdoba was captured by the Christian forces of Castile during the Reconquista.[63]

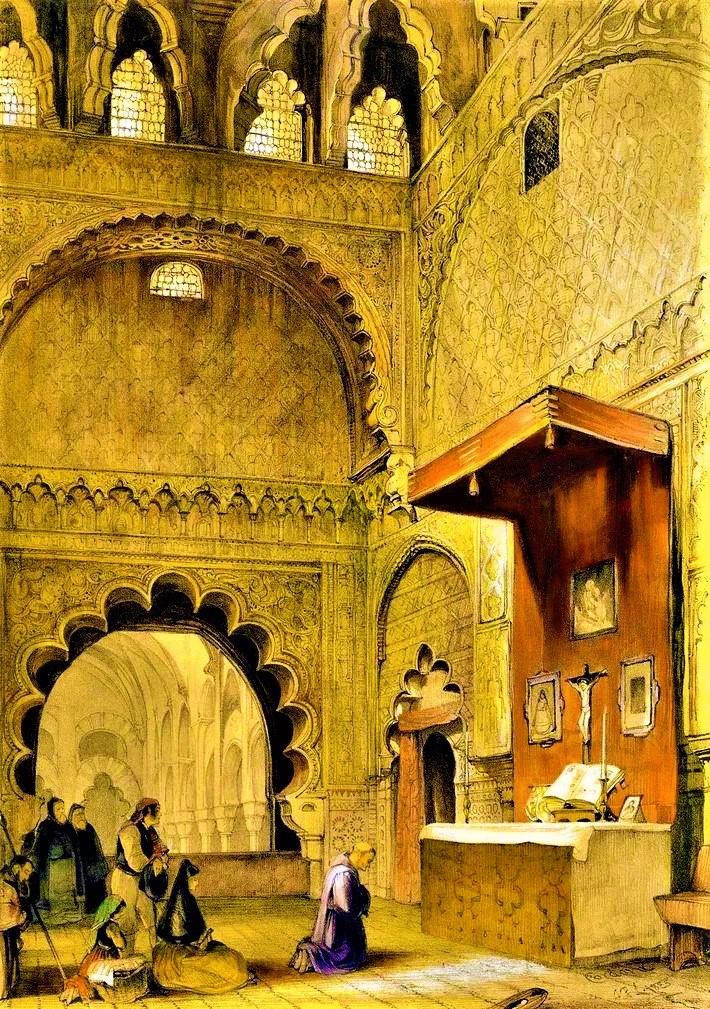

People kneel in prayer at the Royal Chapel of the mosque-cathedral in Córdoba, Spain, in this 1836 engraving by Charles Joseph Hullmandel

The Bottom Line, is that on 30th June 1236, King Ferdinand III of Castile entered the city of Córdoba, putting an end to the five-month siege that his troops had staged around the square. The Spanish Reconquista of Islamic Andalusia was advancing, and Córdoba, capital of the Umayyad caliphate in the 10th century, was the latest to fall. It had once been the brightest and most populous city in Al Andalus. It was also home to one of the world’s marvels of architecture: the Aljama Mosque. [64]

A day before the king entered Córdoba, after the Muslims had already abandoned it, a group of Castilians left the place where they were encamped, entered the walled city through the Algeciras Gate, and went to the Great Mosque. They placed a cross and a flag of Castile atop the minaret. A few hours later, the bishop of Osma sanctified the building and celebrated a dedication mass after consecrating the altar. In a few moments, the magnificent Aljama Mosque had become a Christian cathedral. Today, nearly 13 hundred years later, there is a new battle over the Córdoba Mosque-Cathedral and Spanish Identity[65] According to a report by Malia Politzer of 30th May 2015[66]. “the first time I saw the Córdoba Mosque-Cathedral was during a vacation to Spain.

I remember walking into the building, and feeling a sense of awe as I stared up at the rows of striped arches, dimly lit by elegant brass lamps. Nestled in the heart of the mosque is a cathedral bathed in natural sunlight, with vaulted ceilings carved from stone, creating a unique architectural fusion of Catholic and Muslim, East and West.” However, “My friend Jasmine, a Sudanese Muslim from the United Kingdom, had a very different experience. When she visited the mosque last winter, she too was awed by the arches, the historical significance of the monument, and the golden Mihrab.

But unlike me, she was unable to lose herself in the experience of the mosque-cathedral. A petite woman with dark chocolate skin and a headscarf, she is conspicuously Muslim, and the moment she stepped through the door, she felt watched. A guard in a crisp white shirt, hired by the church to ensure the Christian holy space was respected, was staring at her. She noticed he was always nearby, and wondered if he was following her. Finally, as she neared the Mihrab, he tapped on her shoulder, startling her. Gesturing at her headscarf he told her sternly that Muslims are not permitted to pray inside of the Cathedral. She left shortly after, feeling angry, sad, and unwelcome.”

Essentially, as a Muslim, the cannot perform her Islamic prayer in a building which once was a glorious mosque and she was abruptly reminded by te security to ensure that the Christian cathedral is not desecrated. This stance creates friction, which could ultimately escalate into a major peace disruption. According to Isabel Romero, a Spanish Muslim convert and the director of the Córdoba-based company, Halal tourism, many visiting Muslims have reported similar experiences in recent years. “The Mosque-Cathedral is supposed to belong to all of us. For Muslims, it is one of the most important religious sites, next to Mecca, representing a golden age of Islamic civilization” she explained. “But the Catholic Church is trying to deny that heritage, and claim the site as theirs.”

The Cathedral-Mosque of Córdoba has been called the most important Muslim heritage site in the Western World, drawing 1.5 million visitors each year. Also known as the “Great Mosque of Cordoba,” the site was built on Visigoth ruins in 785, signalling the beginning of seven centuries of Muslim rule of Spain and Portugal. Soon after, Córdoba would become the capital of the Umayyad caliphate, which spanned from Syria, to much of North Africa. As the religious centre of the Caliphate, the mosque would come represent a golden age of Islamic Spain, and contribute to Córdoba’s image as a centre of culture and learning, replete with libraries that boasted more books than the Vatican, universities that attracted scientists and scholars from around the world, and running water. It is also remembered as a time of “Convivencia”, when followers of the three great religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, lived together in peace and harmony, side by side, in Spain. Each of the common group of the Abrahamic faiths were tolerant and not only accommodated, but more importantly respected the faith of their common religious ancestry.

Now, the mosque has become the site of a fierce conflict, pitting local activists against the Catholic Church. The former accuse the Catholic church of erasing the structure’s Muslim past. Today, “mosque” is omitted from the literature distributed on the site, and the audio-guides (produced by the church) treat the seven decades of Muslim rule as an “intervention.” Exploiting a loophole in Spanish property law, the Church is also attempting to claim official ownership of the monument — and, unless challenged by the local government, will become the sole proprietor by 2016.

For Romero, however, the struggle for control over the image and ownership of the mosque goes directly to the question of Spanish identity. “Right now there are two Spains, divided by two visions of what it means to be Spanish,” she explains. “One sees Spanish identity as fundamentally Catholic, tracing our roots back to the reconquest by the Catholic monarchs. The other vision of Spain is essentially multicultural, celebrating our diversity, and the history of convivencia, where we recognize and incorporate the influences of Romans, Celts, Jews and Muslim as a fundamental part of what it means to be Spanish, and give it equal importance to our Catholic heritage.”

Romero pauses, as though looking for the right words. “This second vision is threatening to the Catholic church. The Great Mosque is one of the greatest symbol of Spain’s multicultural past and one that the Church wants to erase.” he conflict over the name of the mosque-cathedral became world news last fall when the monument temporarily disappeared from Google maps. One day, the title “Mosque-Cathedral” was prominently displayed for all to see. The next day, the word “mosque” had disappeared, leaving “Cordoba Cathedral” in its place.

The change provoked immediate and resounding protest. A group of Spanish citizens, outraged by the omission, mounted an online petition on change.org demanding that the word “mosque” be reinstated. The petition notes that “since 2006, when the Church matriculated the monument, we have witnessed an attempt of judicial, economic, and symbolic appropriation of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba by the Bishop of Córdoba. Part of this strategy was to revoke the term ‘mosque’ for the sole word ‘Cathedral,’ erasing with one pen stroke a fundamental part of its history.”[i] Within weeks, the petition had accumulated more than 50,000 signatures, and today has close to 500,000. Last November, Google reinstated the previous name “Mosque-Cathedral,” which had been used since the 1980’s.

Miguel Santiago is a Córdoba native, and the co-founder of the Plataforma para la Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba, patrimonio de todos (Platform for the Mosque-Cathedral, heritage for all) the organization behind the petition. A short, middle-aged man who likes to talk with his hands, Santiago is a local schoolteacher. Though a DEVOUT Catholic, I recently met him in his house, a traditional Córdoba courtyard home.

Though a Catholic, Santiago has become one of the Church’s greatest critics. According to Santiago, last year’s brief Google omission was not a one-off event, but part of a steady campaign by the Church to establish control of the monument over the past 30 years. Removing a heavy binder from a shelf behind him, he flips to a brochure of the monument, published by the Church in 1981. “Here you can see that its Islamic heritage is emphasized,” he said, pointing to the title “Mosque Cathedral,” a term that recognizes its shared heritage. In the description printed in the brochure, the first sentence reads, “The Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba, according to F. Chueca is the first monument of all the western Islam and one of the most impressive of the world.”

The remaining text provides nearly equal weight to its Muslim and Christian heritage. The next brochure, published in 1998, calls the site “Santa Iglesia Cathedral,” and in much smaller letters “former mosque,” which is described in the text as “primitive,” with no further elaboration on what was “primitive” about it. The brochure emphasizes the Roman and Visigoth influences to the architecture of the mosque, which was “built over the Christian Visigoth basilica.” By 2010, according to the brochure, the site is referred to simply as “Córdoba Cathedral;” the 700 years of Muslim rule are an “intervention.” However, the Christian forces captured the Umayyad capital in 1236, but left its glorious house of worship largely untouched when converting it to a cathedral.[67]

Interestingly, the 16th August 2022 issue of National Geographic has an article, titled “Cordoba’s Stunning Mosque-Cathedral showcases Spain’s Muslim Heritage[68], with excellent graphics. This is a reassuring sign, that both the warring parties are catered for, in this reputable journal.

References:

[1] Personal quote by the author, November 2022.

[2] https://image.slidesharecdn.com/plan4003slidesweek02-130128171642-phpapp01/95/urban-form-and-design-key-concepts-historical-precedents-6-638.jpg?cb=1504201840

[3] https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.shutterstock.com%2Fimage-photo%2Fcathedral-toledo-spain-105765104&psig=AOvVaw3r7RohgNd9dWWBWqCrDZf_&ust=1668327412829000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAwQjRxqFwoTCIDnjIiaqPsCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAE

[4] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ferdinand-II-king-of-Spain

[5] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Isabella-I-queen-of-Spain#:~:text=Isabella%20I%2C%20byname%20Isabella%20the,husband%2C%20Ferdinand%20II%20of%20Aragon%20(

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toledo_Cathedral#:~:text=Rosario%20D%C3%ADez%20del%20Corral%20Garnica%20(1987).%20Arquitectura%20y%20mecenazgo%3A%20la%20imagen%20de%20Toledo%20en%20el%20Renacimiento.%20Alianza.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D84%2D206%2D7066%2D9.

[7] https://www.google.com/search?rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&si=AC1wQDBgv4q3A2ojf086TvVgL6tTfKEZW2vrlR3V2uQ-r4wcbln8fPjhZl6SSjw8YWb0xBFTr7qHIjWUDAbB1EQkuX4ofEhMF-yB1URfEg2HG1mjusP-NcQVpottcvalOhzFa9O46ItNi_w4ujhjaEhq4mr6NbPom_M7YC_hSH657vP-b9MnBBwWEOis4YU3_fXhDolxW5Lyrid2VMvXrhrgfxidl00N1xSxrMOH7y58uAQZCoVh53ASQky2mUnhUpDaNYB1OS4RUOpZ7S0JVDPe5t_KFMPv3XSafNFXvJVfbIBwvOh4mus1JSoTLNeHCKOLQvbVPfVK_ewRNElFXQ5SBMxBZ1IRySJJvvCRxvvvXOtzc9rJma4%3D&q=Principles+of+Mahomedan+law+Dinshah+Fardunji+Mulla&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjDzsLv7qj7AhXQhFwKHfW0C4wQs9oBKAB6BAhXEAI

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toledo_Cathedral#:~:text=Angus%20Macnab%2C%20%22The%20Moslim%20Saint%20in%20Toledo%20Cathedral%22%2C%20in%3A%20Studies%20in%20Comparative%20Religion%2C%20Vol.%202%2C%20No.%202.%20(Spring%2C%201968)%20%5B1%5D

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toledo_Cathedral#:~:text=I%2C%20Alfonsus%2C%20Emperor%20of%20Hesperia%20by%20the%20disposition%20of%20God%2C%20grant%20to%20the%20metropolitan%20See%2C%20that%20is%2C%20the%20church%20of%20Saint%20Mary%20in%20the%20city%20of%20Toledo%2C%20the%20complete%20honour%20that%20she%20should%20have%20the%20pontifical%20see%20according%20to%20what%20before%20was%20constituted%20by%20the%20holy%20fathers%E2%80%A6

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Bloom%2C%20Jonathan%20M.%20(2020).%20Architecture%20of%20the%20Islamic%20West%3A%20North%20Africa%20and%20the%20Iberian%20Peninsula%2C%20700%2D1800.%20Yale%20University%20Press.%20ISBN%C2%A09780300218701.

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Kennedy%2C%20Hugh%20(1996).%20Muslim%20Spain%20and%20Portugal%3A%20A%20Political%20History%20of%20al%2DAndalus.%20Routledge.%20ISBN%C2%A09781317870418.

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Bloom%2C%20Jonathan%20M.%3B%20Blair%2C%20Sheila%20S.%2C%20eds.%20(2009).%20%22C%C3%B3rdoba%22.%20The%20Grove%20Encyclopedia%20of%20Islamic%20Art%20and%20Architecture.%20Oxford%20University%20Press.%20pp.%C2%A0505%E2%80%93508.%20ISBN%C2%A09780195309911.

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Barrucand%2C%20Marianne%3B%20Bednorz%2C%20Achim%20(1992).%20Moorish%20architecture%20in%20Andalusia.%20Taschen.%20ISBN%C2%A03822896322.

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Calvert%2C%20Albert%20Frederick%3B%20Gallichan%2C%20Walter%20Matthew%20(1907).%20Cordova%2C%20a%20City%20of%20the%20Moors%20(Public%20domain%C2%A0ed.).%20J.%20Lane.%20pp.%C2%A042%E2%80%93.

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Jayyusi%2C%20Salma%20Khadra%2C%20ed.%20The%20Legacy%20of%20Muslim%20Spain%2C%202%20Vols..%20Leiden%3A%20Brill%2C%20p.599.

[16] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w_99hl6ykpc

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Jayyusi%2C%20Salma%20Khadra%2C%20ed.%20The%20Legacy%20of%20Muslim%20Spain%2C%202%20Vols..%20Leiden%3A%20Brill%2C%20p.599

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Anwar%2C%20G.%20Chejne%2C%20Muslim%20Spain%3A%20Its%20History%20and%20Culture%2C%20MINNE%20ed.%20Minnesota%3A%20University%20Of%20Minnesota%20Press%2C%20p.364.

[19] https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/137398/Mosque-Cathedral-of-Cordoba

[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Jayyusi%2C%20Salma%20Khadra%2C%20ed.%20The%20Legacy%20of%20Muslim%20Spain%2C%202%20Vols..%20Leiden%3A%20Brill%2C%20p.599

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=The%20Literature%20of%20Al%2DAndalus%20(The%20Cambridge%20History%20of%20Arabic%20Literature).%20New%20Ed%20ed.%20New%20York%3A%20Cambridge%20University%20Press%2C%20161.

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=The%20Literature%20of%20Al%2DAndalus%2C%20p.159

[23] The Literature of Al-Andalus (The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature). New Ed ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 161.

[24] Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). “Córdoba”. The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. pp. 505–508. ISBN 9780195309911.

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Jan%2C%20Read.%20The%20Moors%20in%20Spain%20and%20Portugal.%20London%3A%20Rowman%20%26%20Littlefield%20Pub%20Inc%2C%20p.56.

[26] Jayyusi, Salma Khadra, ed. The Legacy of Muslim Spain, 2 Vols.. Leiden: Brill, p.599.

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=S%C3%A1nchez%20Llorente%2C%20Margarita.%20%22Great%20Mosque%20of%20C%C3%B3rdoba%22.%20Discover%20Islamic%20Art%2C%20Museum%20With%20No%20Frontiers.%20Retrieved%206%20December%202020.

[29] https://www.qantara-med.org/public/show_document.php?do_id=168&lang=en

[30] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Barrucand%2C%20Marianne%3B%20Bednorz%2C%20Achim%20(1992).%20Moorish%20architecture%20in%20Andalusia.%20Taschen.%20ISBN%C2%A03822896322.

[31] https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Al_Andalus_The_Art_of_Islamic_Spain

[32] Jerrilynn D. (1992). “The Great Mosque of Córdoba”. In Dodds, Jerrilynn D. (ed.). Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 11–26. ISBN 0870996371.

[33] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=M.%20Bloom%2C%20Jonathan%3B%20S.%20Blair%2C%20Sheila%2C%20eds.%20(2009).%20%22Woodwork%22.%20The%20Grove%20Encyclopedia%20of%20Islamic%20Art%20and%20Architecture.%20Oxford%20University%20Press.%20pp.%C2%A0419%E2%80%93439.%20ISBN%C2%A09780195309911.

[34] https://cvc.cervantes.es/actcult/mezquita_cordoba/fichas/mezquita_c/techumbre.htm

[35] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=%22Los%20Hern%C3%A1n%20Ruiz%2C%20saga%20de%20arquitectos%3A%20Hern%C3%A1n%20Ruiz%20I%2C%20el%20Viejo%22.%20Arte%20en%20C%C3%B3rdoba%20(in%20European%20Spanish).%2015%20June%202015.%20Retrieved%204%20December%202020.

[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=j%20k%20l-,Mar%C3%A7ais%2C%20Georges%20(1954).%20L%27architecture%20musulmane%20d%27Occident.%20Paris%3A%20Arts%20et%20m%C3%A9tiers%20graphiques.,-%5E

[37] https://books.google.com/books?id=IRHbDwAAQBAJ&q=Islamic+Palace+Architecture+in+the+Western+Mediterranean&pg=PP1

[38] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Barrucand%2C%20Marianne%3B%20Bednorz%2C%20Achim%20(1992).%20Moorish%20architecture%20in%20Andalusia.%20Taschen.%20ISBN%C2%A03822896322.

[39] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Bloom%2C%20Jonathan%20M.%20(2020).%20Architecture%20of%20the%20Islamic%20West%3A%20North%20Africa%20and%20the%20Iberian%20Peninsula%2C%20700%2D1800.%20Yale%20University%20Press.%20ISBN%C2%A09780300218701.

[40] https://books.google.com/books?id=K2CBzgEACAAJ

[41] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Stern%2C%20Henri%20(1976).%20Les%20mosa%C3%AFques%20de%20la%20Grande%20Mosqu%C3%A9e%20de%20Cordoue.%20Berlin%3A%20Walter%20de%20Gruyter.

[42] https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Al_Andalus_The_Art_of_Islamic_Spain

[43] Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300218701.

[44] Nuha N. N. Khoury (1996). “The Meaning of the Great Mosque of Cordoba in the Tenth Century”. Muqarnas. 13: 80–98. doi:10.2307/1523253. JSTOR 1523253.

[45] Rosser-Owen, Mariam (2021). “Appendix 3A: Qur’ānic Inscriptions inside the Cordoba Mosque”. Articulating the Ḥijāba: Cultural Patronage and Political Legitimacy in Al-Andalus, the Amirid Regency C. 970-1010 AD. Brill. pp. 404–414. ISBN 978-90-04-46913-6.

[46] Nuha N. N. Khoury (1996). “The Meaning of the Great Mosque of Cordoba in the Tenth Century”. Muqarnas. 13: 80–98. doi:10.2307/1523253. JSTOR 1523253.

[47] https://www.jstor.org/stable/1523329

[48] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=j%20k%20l-,Mar%C3%A7ais%2C%20Georges%20(1954).%20L%27architecture%20musulmane%20d%27Occident.%20Paris%3A%20Arts%20et%20m%C3%A9tiers%20graphiques.,-%5E

[49] https://www.lonelyplanet.com/spain/andalucia/cordoba/attractions/mezquita/a/poi-sig/1189075/360732

[50] https://archive.org/details/islamicgardensla0000rugg/page/152

[51] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=%22Patio%20de%20los%20Naranjos%20%7C%20Web%20Oficial%20%2D%20Mezquita%2DCatedral%20de%20C%C3%B3rdoba%22.%20Patio%20de%20los%20Naranjos%20%7C%20Web%20Oficial%20%2D%20Mezquita%2DCatedral%20de%20C%C3%B3rdoba.%20Retrieved%207%20December%202020.

[52] https://books.google.com/books?id=7giwCQAAQBAJ&dq=charles+v+cordoba+destroyed+something+unique&pg=PA309

[53] “Patio de los Naranjos | Web Oficial – Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba”. Patio de los Naranjos | Web Oficial – Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba.

[54] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=%22Patio%20de%20los%20Naranjos%20%7C%20Web%20Oficial%20%2D%20Mezquita%2DCatedral%20de%20C%C3%B3rdoba%22.%20Patio%20de%20los%20Naranjos%20%7C%20Web%20Oficial%20%2D%20Mezquita%2DCatedral%20de%20C%C3%B3rdoba.%20Retrieved%207%20December%202020.

[55] http://mezquita-catedraldecordoba.es/en/descubre-el-monumento/el-edificio/torre-campanario/

[56] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Hern%C3%A1ndez%20Gim%C3%A9nez%2C%20F%C3%A9lix%20(1975).%20Alminar%20de%20Abd%2Dal%2DRahman%20III%20en%20la%20Mezquita%20Mayor%20de%20C%C3%B3rdoba%3A%20genesis%20y%20repercusiones.%20Granada%3A%20Patronato%20de%20la%20Alhambra.%20ISBN%C2%A084%2D85133%2D05%2D6.

[57] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/9780300218701

[58] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=Hern%C3%A1ndez%20Gim%C3%A9nez%2C%20F%C3%A9lix%20(1975).%20El%20alminar%20de%20%CA%BBAbd%20al%2DRa%E1%B8%A5m%C4%81n%20III%20en%20la%20Mezquita%20Mayor%20de%20Cordoba%3A%20Genesis%20y%20repercusiones.%20Granada%3A%20Patronato%20de%20la%20Alhambra.%20ISBN%C2%A09788485133055.

[59] http://mezquita-catedraldecordoba.es/en/descubre-el-monumento/la-historia/

[60] https://www.artencordoba.com/en/mosque-cordoba/belfry-tower/

[61] “Bell Tower | Web Oficial – Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba”. Bell Tower | Web Oficial – Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba.

[62] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosque%E2%80%93Cathedral_of_C%C3%B3rdoba#:~:text=%22Belfry%20Tower%20of%20the%20Mosque%2DCathedral%20of%20C%C3%B3rdoba%22.%20Arte%20en%20C%C3%B3rdoba.%2022%20July%202020.%20Retrieved%203%20December%202020.

[63] https://www.google.com/search?q=was+there+any+war+when+the+cordoba+mosque+was+changed+to+a+cathedral&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&oq=was+there+any+war+when+the+cordoba+mosque+was+changed+to+a+cathedral&aqs=chrome..69i57.25244j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#:~:text=The%20mosque%20was%20converted%20to%20a%20cathedral%20in%201236%20when%20C%C3%B3rdoba%20was%20captured%20by%20the%20Christian%20forces%20of%20Castile%20during%20the%20Reconquista.

[64] https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/history-and-civilisation/2022/08/cordobas-stunning-mosque-cathedral-showcases-spains-muslim-heritage

[65] https://www.icwa.org/the-battle-over-the-cordoba-mosque-cathedral-and-spanish-identity/

[66] https://www.icwa.org/author/mpolitzer

[67] https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/history-and-civilisation/2022/08/cordobas-stunning-mosque-cathedral-showcases-spains-muslim-heritage#:~:text=Christian%20forces%20captured%20the%20Umayyad%20capital%20in%201236%2C%20but%20left%20its%20glorious%20house%20of%20worship%20largely%20untouched%20when%20converting%20it%20to%20a%20cathedral.

[68] https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/history-magazine/article/cordobas-mosque-cathedral-showcases-spains-muslim-heritage

[69] https://www.icwa.org/the-battle-over-the-cordoba-mosque-cathedral-and-spanish-identity/#:~:text=sad%2C%20and%20unwelcome.-,Mosque%20of%20Cordoba%2C%20credit%20Tomas%20Conde%20Kemme,-According%20to%20Isabel

______________________________________________

READ: PART 2 – PART 3 – PART 4

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Catholic Church, Christianity, Conflict, History, Islam, Religion, Spain

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 14 Nov 2022.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Peace Disruptors–The Conversion and Repurposing of Places of Worship (Part 1): The Great Mosque at Cordoba, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.