Global Symbols of Peace (Part 2): The Peace Flame in Hiroshima

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 17 Apr 2023

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

The Mega Scale of Death and Destruction Humans Have Inflicted on Fellow Humanoids throughout History Knows No Bounds [i]

The eternally burning Peace Flame in front of the Peace Arch in Hiroshima emphasising the “Never Again” philosophy. The specially designed stone lantern is called the Flame of Peace. The lantern is inscribed with the words “Let all the souls here rest in peace, for we shall not repeat the evil.”

17 Apr 2023 – This publication, in the series on the Global Symbols of Peace, is aimed at creating “Peace Awareness” and infuse a miniscule dose of anti-peace disruption reminder to erring humanoids who are constantly transgressing the limits of humanity especially since the beginning of this decade. We, the over eight billion humanoids, as a collective representative of Homo sapiens, sapiens[1], are eternally repeating the same mistakes in our pursuit of material and territorial gains, irrespective of the human cost of our international belligerence. We have ignored to learn from the gross mistakes based on national mis-propaganda and have created intolerable suffering on our fellow humanoids. This is exemplified by the unfounded basis and fruitless war on Terror waged against Iraq by the George W. Bush[2] administration. This destabilised the country of Iraq and eradicated the regime of Saddam Hussein[3], only to be replaced with ISIL[4] terror, which caused mass destruction of humanity, especially involving the Yazidis[5] and massive internal displacement of humanoids. United States is repeating the same misjudgment on its involvement In the Ukraine War[6], with archival philosophies of the war in Vietnam [7]in the 1970’s, all in the name and rationale of preventing the spread of communism, to no avail. Furthermore, the recently leaked, Pentagon Documents[8], “eloquently demonstrates” the hypocrisy of United States in global affairs. It would be a long list of the recurrent belligerent anecdotes, in recent history and a futile reminder, hence the author uses the backdrop of the deployment of the fist atom bomb in history, in a war scenario, to reiterate the elusive pursuit of global peace in the present era, with multiple, global, trouble, hot spots, with the potential of being escalated into full scale world war. The active role players being the West and Non-West. The present international foreign policies of most nations are based on aggression and oppression, forgetting the historical basis for these territorial disputes which are ongoing. In the midst of such disruption of peace, it is refreshing to note that amicability has been restored between Yemeni Houthis [9]and The Royal Kingdom of Saudi Arabia[10], while at the same time it is a new beacon of hope to note the rapidly increasing membership of the BRICS[11] conglomeration, to counteract the dollar based economic dominance of the west in the future. Based on this threat to the West’s materially motivated existence and pursuits, the author is of an opinion that the Pentagon Leaks might be a government orchestrated endeavor, to use the leaks as a justification of and rationale for their extended and ongoing belligerence, with proxy wars, not only in Ukraine, but other covert operations in Africa, Far East, Middle East, as well as in the Latin American countries.

This publication is therefore dedicated to the over one million Japanese, collectively, decimated by the deployment of the two nuclear devices, in 1945, on Japan. The Peace Flame at Hiroshima[12] is a symbol of hope and remembrance for the victims of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, during World War II. The flame is located in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, near the hypocenter of the atomic bomb blast, and burns continuously as a reminder of the devastating consequences of nuclear war. The idea for the Peace Flame was proposed by a group of schoolchildren from Tokyo in 1946, who wanted to create a permanent reminder of the tragedy that had befallen Hiroshima. The flame was first lit on August 1, 1964, during the opening ceremony of the Tokyo Olympic Games[13], and was brought to Hiroshima the following year, where it has burned ever since. The flame is fueled by natural gas and burns in a specially designed stone lantern called the Flame of Peace. The lantern is inscribed with the words “Let all the souls here rest in peace, for we shall not repeat the evil” [14]in both Japanese and English, and is surrounded by a reflecting pool and a cenotaph that lists the names of the victims of the bombing. Every year on August 06th, the anniversary of the bombing, a ceremony is held at the Peace Memorial Park to remember the victims and pray for peace. As part of the ceremony, the Flame of Peace is used to light a torch, which is carried by a relay of runners to the city of Nagasaki,[15] which was also bombed by the United States on 09th August, 1945. The torch is used to light the Peace Flame at Nagasaki, creating a symbolic link between the two cities and a commitment to peace and nuclear disarmament. The Peace Flame has become an important symbol of peace and reconciliation, not only in Japan but around the world. It serves as a reminder of the devastating consequences of war and the importance of working towards a more peaceful and just world. The Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation is a public institution established by the city of Hiroshima in 1965 with the aim of promoting peace and culture both domestically and internationally. The foundation operates various programs and facilities related to peace, including the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, and the International Conference Center Hiroshima. One of the primary objectives of the foundation is to spread awareness about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and to promote the importance of nuclear disarmament. To achieve this goal, the foundation supports research and education related to peace and nuclear disarmament, and hosts various events and activities to promote peace and understanding among different cultures and nations. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, operated by the foundation, is a museum dedicated to preserving the memory of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and educating visitors about the dangers of nuclear weapons. The museum houses a collection of artifacts and exhibits related to the bombing, including personal belongings of the victims, photographs, and documents. It also provides information about the history of Hiroshima before and after the bombing, as well as the city’s efforts towards peace and reconstruction. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park[16], also operated by the foundation, is a large park located in the center of Hiroshima that serves as a memorial to the victims of the atomic bombing. The park contains various monuments and memorials, including the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, the Peace Flame, and the Children’s Peace Monument. Through its various programs and initiatives, the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation continues to promote the message of peace and nuclear disarmament, with the hope of preventing future tragedies like the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

It’s the most recognizable building in Hiroshima, described by TIME as “Hiroshima‘s Eiffel Tower, its Statue of Liberty.” [17] The Genbaku Dome was once an exhibition hall, functioning as the city’s convention center. After the atomic bombing of 06th August, 1945, it was the only major building left standing near the explosion site. “Where the dome rose, only the supporting beams remain, a giant hairnet capping four floors of vacant gray walls, much of their outer skin peeled away, exposing patches of brick,” TIME later explained. “The interior floors are also gone, making the entire structure an accidental atrium. A front doorway leads to nowhere. A metal spiral staircase ascends to nothing. A pillar lies on its side, wires springing like wild hairs.”

The building was originally constructed in 1915 as the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, [18]and was used for various purposes over the years, including as a museum and exhibition space. On August 6, 1945, the building was located just 160 meters from the hypocenter of the atomic bomb blast, and was one of the few buildings in the area to survive the explosion. It is to be noted that the Atomic Bomb Dome was not the drop off point for the nuclear bomb on August 6, 1945. The hypocenter of the atomic bomb explosion was located approximately 160 meters (525 feet) southeast of the dome, over the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome) in Hiroshima, Japan.

Today, the Dome is a UNESCO World Heritage[19] site and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, where it serves as a physical a reminder of the horrific destruction of atomic power and humanity’s power to rebuild. The Atomic Bomb Dome, also known as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, is a preserved ruin of a building that was partially destroyed by the atomic bomb blast on August 6, 1945. Today, the dome serves as a powerful reminder of the devastating consequences of nuclear war and as a symbol of hope for a peaceful future.

The inside of the Atomic Bomb Dome is not open to the public as it is considered a dangerous site due to the instability of the structure. However, visitors can view the dome from the outside and can see the remnants of the building’s interior, such as the exposed steel framework, concrete walls, and broken windows. Near the Atomic Bomb Dome, there is a museum called the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum that contains exhibits and artifacts related to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, including personal items belonging to the victims, photographs, and documents. The museum also has a section dedicated to the history of the Atomic Bomb Dome and its preservation. Visitors to the museum can learn more about the history and significance of the Atomic Bomb Dome and the impact of the atomic bombing on Hiroshima and its people.

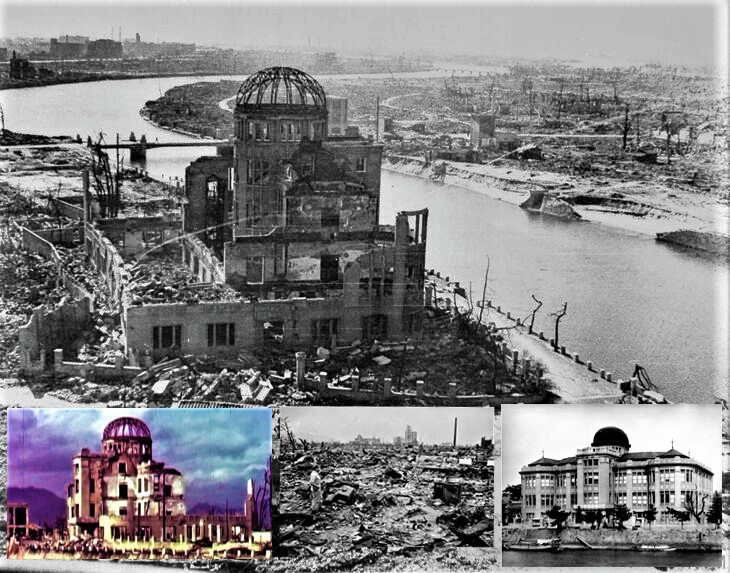

Main Picture The Remains of the Genbaku Dome after the A Bomb.

Inset Right Bottom: The Genbaku Dome complex before the destruction caused by the A Bomb. The Genbaku Dome, also known as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, is a building in Hiroshima, Japan that was one of the few structures to remain standing near the hypocenter of the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945. The building was originally the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, but it was designated the Hiroshima Peace Memorial after the bombing and preserved as a reminder of the devastation caused by nuclear weapons. The Genbaku Dome is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a symbol of the importance of working towards peace and nuclear disarmament. It is located in Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park, which also contains a museum and other memorials dedicated to the victims of the atomic bombing.

Inset Centre Bottom The scale of the massive destruction around the hyopcentre in Hiroshima. Devastation caused by the atomic bomb seen in Hiroshima, Japan. The radius of total destruction was reportedly 1.6 km. “The impact of the bomb was so terrific that practically all living things — human and animal — were literally seared to death by the tremendous heat and pressure set up by the blast,” Tokyo radio said in the aftermath of the explosion, according to a report by The Guardian in August 1945. “All the dead and injured were burned beyond recognition. Those who were outdoors were incinerated to death, while those indoors were killed by the indescribable pressure and heat.” Photograph: War Department/US National Archives/Reuters

Inset Left Bottom: The Remains of the Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima is seen in this color photo taken by the U.S. Army in 1945 Credit: U.S. Army via the Asahi Shimbun.

The question which needs to be raised is how did this mass annihilation of humanoids materialise. The answer lies in a top-secret project, code named The Manhattan Project[20], which was a research and development program during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. The project was initiated in 1939 after the United States received intelligence that Germany was pursuing atomic weapons technology. Led by the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer[21], the project involved many of the top scientists of the time, including Albert Einstein. The project was named after the Manhattan Engineer District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which was responsible for the development of the atomic bomb. The project’s main goal was to create a nuclear weapon that could be used against Germany, although the war in Europe ended before the weapon was ready for use. This shows that the United States government would have deployed the nuclear bomb on Germany, if the device was functional before the end of the war in Europe. In July 1945, the Manhattan Project successfully detonated the first atomic bomb during a test in Alamogordo, New Mexico. Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert [22]about 35 miles (56 km) southeast of Socorro, New Mexico, on what was then the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range, now part of White Sands Missile Range. The only structures originally in the vicinity were the McDonald Ranch House and its ancillary buildings, which scientists used as a laboratory for testing bomb components. A base camp was constructed, and there were 425 people present on the weekend of the test. The code name “Trinity” was assigned by J. Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, inspired by the poetry of John Donne. The test was of an implosion-design plutonium device, informally nicknamed “The Gadget”, of the same design as the Fat Man bomb later detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945. The complexity of the design required a major effort from the Los Alamos Laboratory[23], and concerns about whether it would work led to a decision to conduct the first nuclear test. The test was planned and directed by Kenneth Bainbridge.[24]

Fears of a fizzle did lead to the construction of a steel containment vessel called Jumbo that could contain the plutonium, allowing it to be recovered, although ultimately this was not used in the test. A rehearsal was held on May 7, 1945, in which 108 short tons (98 t) of high explosive spiked with radioactive isotopes were detonated. The Gadget’s detonation released the explosive energy of about 25 kilotons of TNT (100 TJ). Observers included Vannevar Bush, James Chadwick, James Conant, Thomas Farrell, Enrico Fermi, Hans Bethe, Richard Feynman, Leslie Groves, Robert Oppenheimer, Frank Oppenheimer, Geoffrey Taylor, Richard Tolman, Edward Teller, and John von Neumann. The test site was declared a National Historic Landmark district in 1965[25], and listed on the National Register of Historic Places the following year.

Later that year, on August 6 and August 9, 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, leading to the end of World War II.

The Manhattan Project was a highly secret and classified operation, and the full extent of its activities and research was not known to the public until after the war. The project had significant impact on the development of nuclear energy and weapons, as well as on the course of world history. It also raised ethical and moral questions about the use of nuclear weapons and the potential consequences of nuclear war. It is also correct that several German scientists, including Wernher von Braun[26], who had worked on rocket technology for Nazi Germany, were brought to the United States after World War II as part of the Operation Paperclip program to work on various projects, including the Manhattan Project. Von Braun was a leading rocket scientist in Nazi Germany and was responsible for developing the V-2 rocket[27], which was used against Allied targets during the war. After the war, von Braun and a team of other German scientists were brought to the United States to work on rocket technology for the U.S. Army. While von Braun did not work directly on the Manhattan Project, his expertise in rocket technology was crucial to the development of the U.S. space program. He played a key role in the development of the Saturn V rocket that was used in the Apollo moon landings[28].

It is worth noting that the recruitment of German scientists through Operation Paperclip [29]was controversial, as some of these scientists had been involved in war crimes during the war. However, the U.S. government believed that their expertise was too valuable to ignore and decided to bring them to the United States to work on various projects. The plan to bomb Hiroshima was developed by U.S. military leaders, including General Leslie Groves [30]and physicist Robert Oppenheimer, as part of a strategy to force Japan’s surrender and bring an end to the war. Hiroshima was chosen as the target because it was a major military center and had not been heavily bombed during the war, making it an ideal location to test the effects of an atomic bomb. It is reported in annals of history, that the bombing was preceded by a leaflet drop warning Japanese civilians to evacuate the city, but many did not heed the warning. At 8:15 a.m., the bomb was dropped from the Enola Gay, a B-29 bomber, and detonated about 2,000 feet above the city. The explosion released a tremendous amount of energy in the form of heat, blast, and radiation, causing widespread destruction and loss of life. The initial blast killed an estimated 70,000 people, and tens of thousands more died in the following weeks and months due to injuries and radiation sickness. The bombing of Hiroshima was followed by another atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki three days later, leading to Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II. The actual decision to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima was made by the President of the United States at the time, Harry S. Truman[31]. Truman had become President in April 1945, following the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt[32]. At the time, the United States was engaged in a bitter conflict with Japan in the Pacific theater of World War II, and Truman faced a difficult decision about how to end the war quickly and decisively.

Truman was briefed on the Manhattan Project, the top-secret U.S. research program to develop atomic bombs, shortly after taking office. He was informed of the potential power of the bombs and the devastating effects they could have if used in warfare. Truman ultimately decided to use the bombs against Japan as a way to force a surrender and bring an end to the war, rather than launching a full-scale invasion of the Japanese mainland, which was expected to result in massive casualties on both sides.

Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bomb remains controversial, with some arguing that it was necessary to end the war and others contending that it was an unnecessary and immoral act of mass destruction. The decision to use atomic weapons against Japan remains a controversial and heavily debated topic, with some arguing that the bombings were necessary to end the war and others arguing that they were unnecessary and immoral acts of mass destruction.

Main Picture: B29 Super Fortress Bomber Enola Gay which carried the Atom Bomb from Tinian Island and dropped it on Hiroshima on 06th August 1945 just after 0815 am.

Inset Top Left: “The Lucifer of Death”, The Little Boy bomb in the bomb pit, ready for loading into the Enola Gay. The bombs arrived on the island by plane and were kept under extremely heavy guard. The final assembly of the bombs took place on Tinian Island. The men stationed on the island needed to build a separate building for the assembly of the bombs and that every part of that building needed to be grounded against lightning strikes.

Inset Middle: Colonel Paul Tibbets who commandeered the Enola Gay, waving just before his departure with his deadly payload. Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. (23 February 1915 – 1 November 2007) was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force. He is best known as the aircraft captain who flew the B-29 Superfortress known as the Enola Gay (named after his mother) when it dropped a Little Boy, the first of two atomic bombs. He waves from his cockpit before take-off from Tinian Island in Northern Marianas, August 6, 1945. After serving in Europe and North Africa earlier in the war, Tibbets was assigned to the atomic bomb project in 1944 and was put in charge of flight tests before he dropped the bomb on Hiroshima.

Inset Top Right: The Mushroom Cloud over Hiroshima taken just after the Explosion by the US Airforce Photographing Plane.

“Little Boy” Specifications”[33]

Length: 120.0 inches (10 feet / 3.0 meters)

Diameter: 28.0 inches (71.1 cm)

Weight: 9,700 lbs (4,400 kg)

Yield: 15 kiltons (+/- 20%)[34]

The Enola Gay [36]was accompanied by two other B-29 bombers, the Great Artiste and the Necessary Evil, which were tasked with observing the effects of the atomic bomb and gathering data. The Enola Gay and its accompanying planes flew over the Japanese city of Hiroshima at around 8:15 a.m. local time, and the atomic bomb was dropped from the Enola Gay about a minute later. After dropping the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the Enola Gay and its accompanying planes, the Great Artiste and the Necessary Evil, returned to the North Field airbase on the island of Tinian in the Northern Mariana Islands[37]. The Enola Gay and its crew landed safely at around 2:58 p.m. on August 6, 1945, completing a round-trip flight of approximately 12 hours. The crew was met with great excitement and celebration upon their return, as news of the successful mission quickly spread throughout the base and around the world.

Following the end of World War II, the Enola Gay was flown to the United States and became part of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s [38]collection in 1949. It has been on display at the museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia[39] since 2003, where it remains a significant artifact of both World War II and the development of nuclear weapons.

Colonel Paul W. Tibbets Jr[40]., born on February 23, 1915, was a United States Air Force pilot who played a significant role in the development and deployment of the atomic bomb during World War II. Tibbets was the pilot of the Boeing B-29 bomber named Enola Gay, which dropped the atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.

Tibbets began his military career as an enlisted flying cadet in 1937 and quickly rose through the ranks, becoming a captain in 1942. In 1944, he was selected to head the 509th Composite Group, a special unit of the U.S. Army Air Forces that was tasked with developing and deploying atomic bombs.

As the head of the 509th Composite Group, Tibbets oversaw the training and preparation of the crew that would fly the Enola Gay on its mission to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. He was also responsible for selecting the target and coordinating with other military leaders to ensure the success of the mission.

After the war, Tibbets continued to serve in the Air Force, eventually retiring as a brigadier general in 1966. He remained a controversial figure for the rest of his life, with some hailing him as a hero for his role in ending the war and others criticizing him for his part in the devastation caused by the atomic bomb.

Tibbets passed away on November 1, 2007, at the age of 92. Despite the controversy surrounding his legacy, he remains an important historical figure who played a pivotal role in the development and use of nuclear weapons during World War II.

The crew of the Enola Gay, the B-29 bomber that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, did not suffer from radiation sickness as a result of carrying the bomb. The atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki did cause significant vibrations and shockwaves, which could have been felt by the Enola Gay and its crew. However, the plane was flying at a safe distance from the point of detonation, and the vibrations and shockwaves were not strong enough to damage the aircraft. The Enola Gay was specifically designed and modified for the mission to drop the atomic bomb, with reinforced floors and other structural enhancements to withstand the shock of the bomb’s explosion. The crew members also wore earplugs and were instructed to brace themselves during the detonation in order to minimize any potential impact on their hearing or physical well-being. While the Enola Gay likely experienced some degree of vibrations and shockwaves from the atomic bomb explosions, it did not suffer any significant damage as a result.

The bomb, known as “Little Boy[41],” was a uranium-based bomb that used a gun-type design to create a chain reaction and release its destructive energy. It did not produce a significant amount of radioactive fallout, as it exploded at an altitude of approximately 1,900 feet above ground level, which limited the spread of radioactive materials. However, the crew did take precautions to protect themselves from potential radiation exposure. They wore special clothing and used protective shielding on the aircraft to minimize their exposure to radiation. The crew also underwent medical examinations after the mission to ensure they had not been exposed to dangerous levels of radiation. The other military personnel who were involved in the aftermath of the bombing, such as those who participated in the cleanup of the radioactive debris and those who were exposed to radiation during subsequent atomic bomb tests, did suffer from radiation sickness and other health problems. The atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were detonated automatically using a barometric trigger mechanism, also known as an altimeter or air pressure switch. The bombs were designed to detonate at a predetermined altitude above the ground in order to maximize their destructive power. The exact altitude at which the bombs were detonated varied, but in both cases, it was several hundred meters above the ground. The barometric trigger mechanism worked by measuring changes in air pressure as the bomb fell through the atmosphere. When the bomb reached the predetermined altitude, the air pressure triggered an electrical switch that initiated the detonation sequence. The use of automatic detonation mechanisms was critical to the success of the atomic bombings, as it allowed the bombs to be dropped from a safe distance and minimized the risk of premature detonation or failure to detonate.

The target was the city center, specifically the T-shaped Aioi Bridge, which served as a navigation point for the bomber crew. The bomb exploded about 600 meters above the ground, unleashing a massive blast and fire that destroyed much of the city, including the surrounding buildings, homes, and infrastructure. The decision to drop the first atomic bomb on Japan was made by President Harry S. Truman and his advisors, who weighed various factors in choosing the target. One key consideration was the strategic importance of the target. The United States was in the midst of a war with Japan, and the military leadership believed that a demonstration of the bomb’s destructive power would help bring about a quicker end to the conflict. They identified several potential targets in Japan, including Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and Nagasaki, based on factors such as their military and industrial importance and their relative vulnerability to attack. Hiroshima was ultimately chosen as the first target, based on its importance as a transportation hub and military center, as well as its relatively flat terrain, which would allow for a more accurate targeting of the bomb. The decision was made despite the fact that the city had not been heavily bombed up to that point, which would allow for a clearer assessment of the bomb’s impact. Another factor in the decision was the urgency of the situation. The United States was racing against the clock to develop and deploy the bomb before Japan could mount a successful defense or surrender. The decision to drop the bomb was made quickly, without consulting Japan or seeking international approval. The decision to drop the first atomic bomb on Japan was a complex and controversial one, with many ethical and strategic considerations, which were possibly not considered at the critical decision-making, final stage.

The decision to drop the second atomic bomb on Japan was made by President Harry S. Truman and his advisors, following the successful test of a plutonium-based bomb known as “Fat Man[42].”

While some members of Japan’s military leadership were willing to surrender, others remained committed to continuing the war effort, and the Japanese government did not respond to calls for surrender. In the days following the bombing of Hiroshima, the United States demanded that Japan surrender unconditionally, or face “prompt and utter destruction.” When Japan did not respond, the decision was made to drop a second atomic bomb on a different target.

On August 9, 1945, the second atomic bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people and causing widespread destruction. The bombing, combined with the earlier bombing of Hiroshima, convinced Japan’s leadership that the United States possessed a devastating new weapon[43], and they agreed to surrender on August 15, 1945.

The decision to drop the second atomic bomb remains controversial, with some arguing that it was unnecessary and constituted a war crime, while others maintain that it was a necessary measure to bring about an end to the war and save lives that would have been lost in a potential invasion of Japan.

The actual point of drop off of the Nagasaki bomb, known as “Fat Man,” was over the city of Nagasaki, Japan. The bomb was dropped from a B-29 bomber named Bockscar, piloted by Major Charles W. Sweeney. The bombing occurred on August 9, 1945, at approximately 11:02 am local time. The bomb exploded at an altitude of approximately 1,650 feet above ground level, with a yield equivalent to approximately 21,000 tons of TNT.

The target for the bombing was the city of Kokura, but due to cloud cover and smoke from previous bombing runs, Bockscar was forced to divert to its secondary target, Nagasaki. The city was a major center for industry and transportation, and was home to a large number of military personnel. The bombing of Nagasaki killed an estimated 40,000 people and caused widespread destruction, leading to Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II.

There is also a memorial in Nagasaki, Japan, dedicated to the victims of the atomic bombing that occurred there on August 9, 1945.

The memorial, called the Nagasaki Peace Park, is located in the city’s Urakami district, near the hypocenter of the bombing. The park includes a number of monuments, including the Peace Statue, which depicts a figure with an outstretched arm pointing to the sky, symbolizing both the atomic bomb and a desire for peace. There is also a Peace Flame, similar to the one in Hiroshima, which has been burning continuously since it was lit in 1968. The flame is meant to symbolize the hope for peace and the prevention of nuclear war. The Nagasaki National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims is also located within the Peace Park. The hall is dedicated to the memory of the victims of the bombing, and includes exhibits and information about the bombing and its aftermath. In addition to the Peace Park, there are several other memorials and museums in Nagasaki dedicated to the atomic bombing, including the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum and the Nagasaki National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims.

The Agonising End to Humanity in Hiroshima – Police pour cooking oil over junior high school children to soothe their burns. Photo was taken on the Miyuki Bridge between 11 a.m. and 11:30 a.m. about 1.4 miles from the hypocenter, Hiroshima, Japan, Aug. 6, 1945.

Yoshito Matsushige / Chugoku Shimbun

The immediate cause of death for most people who were killed in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was the intense heat and blast effects of the explosions. The firestorms and pressure waves created by the explosions completely destroyed buildings and other structures, and caused widespread devastation and death.

However, in the days, weeks, and months following the bombings, many more people died or suffered long-term health effects as a result of radiation exposure. The intense radiation released by the bombs caused widespread acute and chronic radiation sickness[44], which can cause a range of symptoms including nausea, vomiting, skin burns, hair loss, and decreased organ function. In some cases, radiation sickness can be fatal.

So while the immediate cause of death for most people was the heat and blast effects of the explosions, the long-term health effects of radiation exposure also contributed to the overall death toll and suffering caused by the bombings. The intense heat produced by the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was caused by the energy released from the nuclear fission reactions at the center of the explosions.

The atomic bombs [45]used in these attacks were designed to release a tremendous amount of energy in a very short period of time. When the bomb was detonated, a small amount of uranium or plutonium was rapidly split apart, or “fissioned”, releasing an enormous amount of energy in the form of heat and radiation. This energy was initially released in the form of a bright flash of light, which caused the temperature in the area immediately surrounding the explosion to rise to several million degrees Celsius within a fraction of a second. This intense heat generated a fireball, which expanded rapidly outward, incinerating everything in its path and causing widespread destruction and death. In addition to the direct heat effects of the explosion, the fireball also generated intense thermal radiation, which could cause severe burns and other injuries even at significant distances from the blast site. many of the people who died in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were cremated by the intense heat generated by the explosions. The temperatures near the hypocenters of the explosions were estimated to have reached over 3,000 degrees Celsius (5,400 degrees Fahrenheit), which was more than enough to ignite flammable materials like wood and paper, as well as to vaporize human tissue. This meant that many of the victims were burned beyond recognition, and in some cases their remains were reduced to ashes. The destruction caused by the bombs also made it difficult to identify many of the victims, and in some cases entire families were killed, leaving no surviving relatives to identify them. In the aftermath of the bombings, workers were tasked with collecting and sorting through the remains of the dead, many of which were unidentifiable due to the extent of the burns and other injuries.

The profound level of suffering of the Japanese was captured by a newspaper photographer. On the morning of 06th August, 1945, a photographer roamed through the rubble of Hiroshima, Japan. His images were the only ones known to have been taken that day of people who had been exposed to the atomic blast. While at the time, these photographs remained unknown. However, half a century later, Yoshito Matsushige told his story to Max McCoy[46], a reporter visiting Japan from Kansas. McCoy speaks with The World’s host Marco Werman about the photographer who captured the devastation across the city on film that day. Marco Werman, was asked “Can you set the scene for us that day, when Yoshito Matsushige took his camera out?” Max McCoy: responded that Yoshito Matsushige [47]didn’t take any photographs for quite a while. He could not bring himself to do it. Finally, he did take some photographs at a place called the Miyuki Bridge. At this location, there was a policeman at a table writing out relief certificates for rice for the survivors. The policeman was heavily bandaged. There was a group of junior high school students clustered on the bridge seeking relief. The only thing that the police could think to do for them was to put cooking oil on their wounds. His most reproduced photographs were on the bridge. And looking at them, you might think that the junior high school students, that their clothes are in tatters and hanging down. But what you’re really seeing is their skin, that the bomb flayed them and their skin is hanging down. And so it’s quite moving and quite horrifying. After Matsushige finished the photographs on the bridge and it took him several minutes on the bridge to work up the courage to trip the shutter, he could not take anymore and he just went home.

“It is so horrifying and speaks of the immeasurable destruction of nuclear weapons. So you knew the Matsushige story when you went to Hiroshima in 1986. What was it like to be in that city meeting Matsushige face-to-face?”

“Well, I did have a powerful sense of history. I knew the story. I knew that he had taken the only photographs on the ground. I wanted to walk with him into the city, the route that he traced. So I did, along with an interpreter, who was explaining what he was saying, and I was taking photographs at the same time.

What did he tell you on that walk about his own memories of that day, beyond the photos?

He told me that he was confused about what had happened, that it was beyond belief. This is a phrase that was repeated to me by the survivors. He said that he remembered passing swimming pools that were choked with bodies, people sought water after the bomb, and they ended up dying in swimming pools or ponds or jumping into the river. I recall that he told me about streetcars that were packed with corpses and he could not bring himself to take photographs there. There are so many scenes that he was just unable to photograph, as well. I mean, that he couldn’t push the shutter because the site was so pathetic. It says everything. What did you see in him the day that you met him? What did you see in him that suggested how present August 6 was for many decades later? Was he still living it?

He was when we went to the bridge and he seemed to be seeing those images in his mind. Matsushige was a very reserved individual a snappy dresser, chain smoker, a dedicated newspaper photographer. I recognized a lot of me in him in terms of approach to work, etc. But when we got to the bridge, time seemed to fall away. And what he was describing seemed to be happening before him. And I took one photograph of him in which he’s gesturing and he brought his camera, his modern Nikon with him at the time, but he’s gesturing and you can see it in his face that he has been transported back to 1945.

Max, you’ve written that a photograph is forever a slice of time capturing a testament of the eternal now. So, how are those images from August 6, 1945 Matsushige’s images, how do they inhabit our minds today and the world we live in right now?

I think you have to make room for them. They seem so alien to us and I believe that you have to be able to recognize how awful we can be to each other. And I’ve heard lots of criticism over the years and people saying, “well, you know, the Japanese brought it on themselves, and this is what they get.” This misses the point. This is not about punishment. This is not about retribution. This is about the survival of humanity. And I think the testimony of those who were on the ground when the bomb was dropped is properly the way we should view it. And I also felt badly for Matsushige, because he was, I think, forever remembering these moments and I think he thought he failed.

“In what way?”

Well, he was ashamed of having taken the photographs, a sense of shame about revealing his neighbors in such a distressed state. On the other hand, he also felt that he didn’t take enough. He had a full roll of film in his camera and he only took the five. But in the end, of course, he succeeded, because these are the only photographs taken on the ground. This is the glimpse of the first atomic bombing. And they only suggest the horror. So that’s the power of photographs. What about just meeting Mr. Matsushige? How did that change you and your own understanding of what happened on August 6, or just war generally?

It has stuck with me and it has changed me in ways that I had not expected. The more I think about his personality and his reserve, his calm and how he approached that experience, [it] has taught me to deal with some of the more difficult challenges in journalism. I should say, Matsushige was transformed. After the bombing, he made a specialty of photographing children in the peace park in Hiroshima. And so, he made a conscious effort to, in his word[s], to say this is why it’s important. This is why photographs are important. This is what we should concentrate on. Since that time, I have become resigned, that you will never change some people’s minds about this, but also more convinced that it is important to try.[48]

Bottom Line is that the impact of the The Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) is the only structure left standing near the hypocenter of the first atomic bomb which exploded on 6 August 1945, and it remains in the condition right after the explosion. Through the efforts of many people, including those of the city of Hiroshima, this ruin has been preserved in the same state as immediately after the bombing. Not only is it a stark and powerful symbol of the most destructive force ever created by humankind, it also expresses the hope for world peace and the ultimate elimination of all nuclear weapons. The inscribed property covers 0.40 ha in the urban centre of Hiroshima and consists of the surviving Genbaku Dome (“Genbaku” means atomic bomb in Japanese) within the ruins of the building. The 42.7 ha buffer zone that surrounds the property includes the Peace Memorial Park.

The most important meaning of the surviving structure of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial is in what it symbolises, rather than just its aesthetic and architectural values. This silent structure is the skeletal form of the surviving remains of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall. It symbolises the tremendous destructive power, which humankind can invent on the one hand; on the other hand, it also reminds us of the hope for world permanent peace.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) is a stark and powerful symbol of the achievement of world peace for more than half a century following the unleashing of the most destructive force ever created by humankind.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) has been preserved as a ruin. It is all that remains of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall ‘Hiroshima-ken Sangyo Shoreikan’ after the 1945 nuclear bomb blast. Inside the property, all the structural elements of the building remain in the same state as immediately after the bombing, and are well preserved. The property can be observed from the outside of the periphery fences and its external and internal integrity is well maintained. The buffer zone, including Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, is defined both as a place for prayer for the atomic bomb victims as well as for permanent world peace.

In the last three conservation projects (1967, 1989-1990 and 2002-2003), minimum reinforcement with steel and synthetic resin was used in order to preserve the condition of the dome as it was after the atomic bomb attack. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) stands in its original location and its form, design, materials, substance, and setting are all completely authentic. It also maintains its functional and spiritual authenticity as a place for prayer for world peace and the ultimate elimination of all nuclear weapons.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial is designated as a historic site under Japanese 1950 Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties[49], and is managed by Hiroshima City under the guidance by the Hiroshima Prefectural Government and the Government of Japan. Financial and technical support is available from the Government of Japan. The park management office of Hiroshima City is located inside the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, and daily maintenance is conducted in cooperation with the division in charge of protecting cultural properties. Hiroshima City also conducts a detailed survey of its condition once every three years. A city beautification plan was developed by Hiroshima City that calls for this area to remain an attractive space appropriate to a symbol of the International Peace Culture City. Based on this beautification plan, landscape management standards seek to implement consultation for building height and alignment, as well as wall colours, materials and advertisement boards in the vicinity of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park included within the buffer zone. The protection of Peace Memorial Park was enhanced in 2007 with its designation as a Place for Scenic Beauty under the 1950 Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties.

In 1945, students in the second-year west class of Hiroshima Prefectural Second Girls’ High School suffered from the atomic bombing at a site where they had been mobilized to work.

“I am sorry, miss,” one of the students is recorded as saying in her dying words. “I failed to take the final roll call properly.” The words are attributed to the president of the west class, who is remembered as having a strong sense of responsibility. She and her classmates, who would have been second-year junior high school students by today’s standards, were working only 1.1 kilometers from ground zero. All but one of the 39 students at the site died within two weeks of the bombing. The last moments of the individual students are documented in “Hiroshima Daini Kenjo Ninen Nishi-Gumi” (Hiroshima Prefectural Second Girls’ High School, Second-Year West Class), a book by Chieko Seki.

The students joined hands when they ran for safety, only to get separated because their skin was slipping off from burns. They were taken to a hospital, where they were denied medicine because, in the words of officials, they were beyond help.

Seki, the author, was also a student in the west class, but she escaped death because she stayed home sick from school that day. She writes in her book that she was told she was “lucky” to survive, but then asks: Does that mean that those who were killed in the atomic bombings were just “unlucky”? Three-quarters of a century have passed since the atomic bombs took 140,000 and 70,000guiltless lives in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively. Nuclear weapons continue to exist in the world, where they remain on standby for use.

Perhaps all of us contemporaries of the atomic age are only narrowly surviving.

Nuclear war has come within an inch of erupting on several occasions due to misinformation that a missile attack was launched by an adversary country, a former U.S. secretary of defense told The Asahi Shimbun during an interview.

That kindness is revealed in a story he told me about the day after the bomb was dropped. He came across a little boy who asked only for a glass of water. So he helped him. He went for water but when he returned the little boy had died.

And who knows, perhaps on the 100th anniversary of that death-filled day, when my son, Max, is 33, he’ll visit Hiroshima with his son, tell him of his first visit with his parents and say aloud, for all of us, “Never again.”[50]

Today, the Atomic Bomb Dome stands as a powerful symbol of the human toll of war and the importance of working towards peace and nuclear disarmament. It is located in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, along with other memorials and monuments dedicated to the victims of the atomic bombing. The dome serves as a reminder of the catastrophic consequences of nuclear war and the need to prevent such a tragedy from ever happening again.

Main Picture: A battered sculpture of a Buddha, praying for humanity, stands witness on a hill above a burn-razed valley in Nagasaki. A second bomb, ‘Fat Man,’ dropped over Nagasaki on 9th August 1945, exploded with the force of 21 kilotons of TNT, killing another 70,000 people and finally prompting Japan’s surrender. The bomb flattened buildings within a one-mile radius of the blast, more destruction being prevented by the geographical boundary of the valley, as captured in the colourised photo. Note the Shinto, partly damaged, proudly stands in the background, with hope for humanity.

Inset Photo: The Iconic Hiroshima Peace Arch visited by the then Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and then-U.S. President Barack Obama take part in a wreath-laying ceremony at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial on May 27, 2016.

It is to be noted that Obama never formally apologised, at the ceremony, for deploying two weapons of mass destruction on the Japanese people. DOUG MILLS / THE NEW YORK TIMESTop of Form

Note the preserved remnant shell and dome of the Genbaku Dome in the background, as a fitting backdrop to sustained, Global Peace.

References:

[i] Personal quote by the author April 2023

[1] https://www.britannica.com/topic/Homo-sapiens

[2] https://www.britannica.com/event/Iraq-War

[3] https://www.bing.com/search?q=saddam+hussein&filters=dtbk:%22MCFvdmVydmlldyFvdmVydmlldyEyZjVjNDM4ZC05YTM1LTM1NzctYTc5My0zMGYwOTlhODkxNjI%3d%22+sid:%222f5c438d-9a35-3577-a793-30f099a89162%22+tphint:%22f%22&FORM=DEPNAV

[4] https://www.history.com/topics/21st-century/isis

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yazidism

[6] https://www.aljazeera.com/tag/ukraine-russia-crisis/

[7] https://www.britannica.com/event/Vietnam-War

[8] https://www.cnn.com/2023/04/10/politics/classified-documents-leak-explainer/index.html

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Houthi_movement

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saudi_Arabia

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiroshima_Peace_Memorial_Park

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1964_Summer_Olympics

[14] https://peace-tourism.com/en/spot/entry-46.html

[15] https://www.city.nagasaki.lg.jp/

[16] https://www.bing.com/search?q=hiroshima+peace+memorial+park&filters=dtbk:%22MCFjZ192NV9mYWN0cyFvdmVydmlldyFjOThjMzdlMS0zZTBlLWE3NWMtZWMyYS0wZWUxMmUyNWMzMzc%3d%22+sid:%22c98c37e1-3e0e-a75c-ec2a-0ee12e25c337%22+tphint:%22f%22&FORM=DEPNAV

[17] https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=TIME+as+%e2%80%9cHiroshima%e2%80%98s+Eiffel+Tower%2c+its+Statue+of+Liberty.%e2%80%9d&qpvt=TIME+as+%e2%80%9cHiroshima%e2%80%98s+Eiffel+Tower%2c+its+Statue+of+Liberty.%e2%80%9d+&FORM=VDRE

[18] https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/hiroshima-prefectural-industrial-promotion-hall-now-called-the-a-bomb-dome/4AFVcEbGifeZGQ

[19] https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/775

[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manhattan_Project

[21] https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=j.+robert+oppenheimer&cbn=KnowledgeCard&stid=b2f5fe81-058e-ceac-db32-1a7a8d002c50&FORM=KCHIMM

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jornada_del_Muerto

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Los_Alamos_National_Laboratory

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trinity_(nuclear_test)

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_U.S._National_Historic_Landmarks_by_state

[26] https://www.bing.com/search?q=wernher+von+braun&filters=dtbk:%22MCFvdmVydmlldyFvdmVydmlldyFlMjJiMzM5ZC01ZTZhLTA3ZGMtNGVlYi1jZTEwZTg2Zjk0Njc%3d%22+sid:%22e22b339d-5e6a-07dc-4eeb-ce10e86f9467%22+tphint:%22f%22&FORM=DEPNAV

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V-2_rocket

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Apollo_missions

[29] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Paperclip

[30] https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/profile/leslie-r-groves/

[31] https://www.bing.com/search?q=harry+s.+truman&filters=dtbk:%22MCFvdmVydmlldyFvdmVydmlldyE4MGRhN2ViMi04OWJiLTA2ZTAtMDRhYy0wZWEyYzE0ZDkxODY%3d%22+sid:%2280da7eb2-89bb-06e0-04ac-0ea2c14d9186%22+tphint:%22f%22&FORM=DEPNAV

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franklin_D._Roosevelt

[33] https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2020/08/06/little-boy-the-first-atomic-bomb/

[34] https://www.atomicarchive.com/media/photographs/little-boy_fat-man/little-boy-2.html

[35] https://www.bing.com/search?q=boeing+b-29+superfortress&filters=dtbk:%22MCFvdmVydmlldyFvdmVydmlldyE1YmU3ZTY2MS1iNTM2LTIzZDQtMWEyNy1mNTdlNTQ0Njg2YjM%3d%22+sid:%225be7e661-b536-23d4-1a27-f57e544686b3%22+tphint:%22f%22&FORM=DEPNAV

[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enola_Gay

[37] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tinian

[38] https://airandspace.si.edu/

[39] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steven_F._Udvar-Hazy_Center

[40] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Tibbets

[41] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Boy

[42] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fat_Man

[43] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Sweeney

[44] https://www.bing.com/search?q=acute+radiation+syndrome&filters=dtbk:%22MCFrZ192NF9zeW1wdG9tcyFvdmVydmlldyEyYzRjZTBhNS0xYzg0LTM3MTUtZWI5ZS1iMzhjNzUyZTVlODQ%3d%22+sid:%222c4ce0a5-1c84-3715-eb9e-b38c752e5e84%22+tphint:%22f%22&FORM=DEPNAV

[45] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atomic_bombings_of_Hiroshima_and_Nagasakishinto

[46] https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-opinion-hiroshima-wwii-nuclear-weapons-ukraine-photojournalism-20220805-lhcbq43gcrfsjbvus3qi3ponta-story.html

[47] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoshito_Matsushige

[48] https://theworld.org/stories/2021-08-06/only-photos-hiroshima-taken-august-6-1945

[49] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Property_(Japan)

[50] https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2022/08/05/commentary/japan-commentary/hiroshima-bombing-anniversary/

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Culture of Peace, Peace, Peace Culture

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 17 Apr 2023.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Global Symbols of Peace (Part 2): The Peace Flame in Hiroshima, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.