To Meet EV Demand, Industry Turns to Technology Long Deemed Hazardous

ENVIRONMENT, 22 May 2023

Rebecca Tan, Dera Menra Sijabat and Joshua Irwandi | The Washington Post - TRANSCEND Media Service

Indonesia is richly endowed with nickel, but refining this crucial mineral poses a daunting environmental challenge.

Dust and smoke rise from the Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park’s nickel-mining facility on Halmahera island, in Indonesia’s North Maluku province.

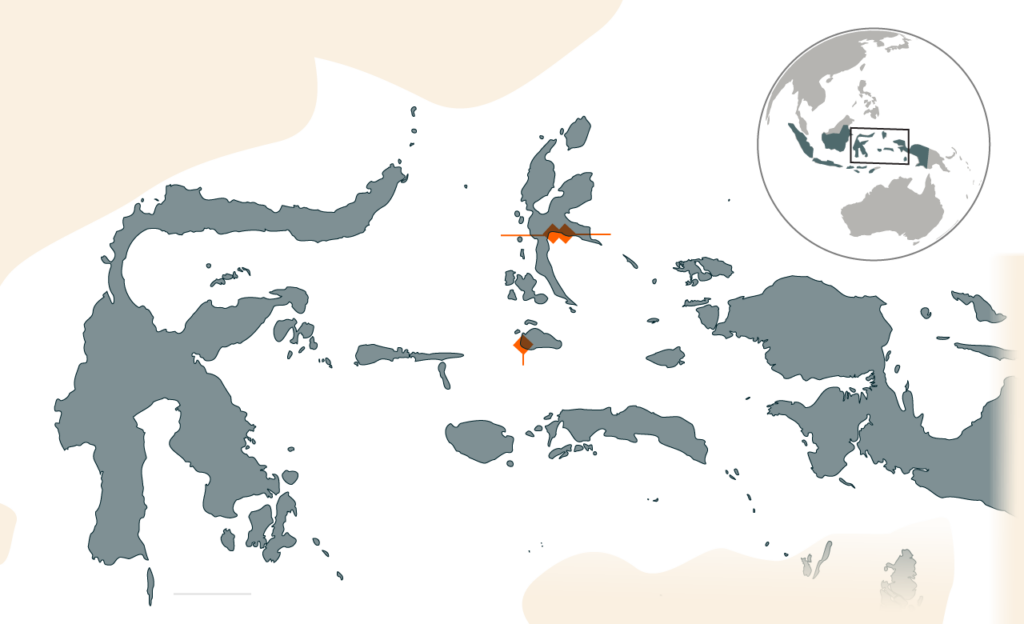

10 May 2023 – On a remote island close to where the Pacific meets the Indian Ocean sits one of the first refineries built specifically to support the world’s transition away from fossil fuels.

Rocks unearthed here contain traces of nickel, a key ingredient in electric vehicle batteries. Extracting it, refining it and readying it for export is a gargantuan task.

More than $1 billion has been sunk into the processing facility, the first in Indonesia to use an acid-leaching technology to convert low-grade laterite nickel ore — which the country has in abundance — into a higher-grade material suitable for batteries. Foreign investors and lenders cite the project as evidence of their commitment to fighting climate change.

But the sprawling facility, bordered on one side by forest and on the other by blue seas, faces a major challenge: what to do with the roughly 4 million metric tons of toxic waste produced every year — enough, approximately, to fill 1,667 Olympic-size swimming pools.

In 2020, the companies behind the project told the government they had a solution: They would pump the waste into the ocean. They ultimately backtracked in the face of public pressure. But it’s not clear that the on-land storage alternative they’ve offered instead is significantly safer.

Indonesia is the world’s top producer of nickel by a wide margin, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Along with Australia, the country has the largest nickel reserves left on Earth.

And as global demand for nickel surges, company executives and Indonesian government leaders are turning to a refining technology long considered too risky to embrace, too perilous for the environment and for local communities.

This technology, using acid under conditions of intense heat and pressure to remove nickel from raw ore, has never been tested before in Indonesia, where the frequency of earthquakes, heavy rainfall and landslides can make it especially treacherous to transport and store hazardous waste. The process poses steep environmental costs that have yet to be reckoned with, according to interviews with more than 40 people familiar with the country’s nickel industry, visits to six largely isolated mining villages in eastern Indonesia and visual analyses by mining experts.

Indonesian officials say this new refining technology is needed to harness these nickel resources, which they hope will transform the country’s future as oil did for Saudi Arabia. At least 10 other projects using this same technology are already under development, according to the Indonesian Nickel Mining Association.

A facility in a nickel-mining complex in the village of Kawasi on Obira island. Mining runoff has turned the waterway behind it a reddish brown.

Officials have made it a priority to build a nickel supply chain, banning the export of raw nickel ore for processing abroad and approving the development of acid-based refining facilities as well as additional conventional nickel smelters at a rate unparalleled elsewhere. Despite official pledges to reduce carbon emissions, the government has approved the construction of coal-fired power plants specifically to support the processing of nickel for the EV industry.

Much of the nickel in EV batteries used by automakers such as Tesla, Hyundai and Ford is already sourced from Indonesia by way of battery manufacturers in China. And by 2030, when global nickel demand is forecast to be 52 percent higher than in 2020, Indonesia will probably churn out more than two-thirds of the supply, according to estimates from Macquarie Group, an Australian financial services group with expertise in the mining sector.

The surging interest in nickel is part of the global boom in demand for a range of metals used in making EVs, which typically require six times the mineral inputs of their fossil-fuel burning counterparts to make them run. But while the transition to EVs is widely considered essential in addressing climate change, there has often been little recognition of the toll that extraction and processing of these raw materials — including technologies now urgently needed to produce the quantity and quality of minerals required — will take on the lives and livelihoods of local communities and the surrounding environment.

Laterite nickel ore comes in two forms, and until recently there was no need to use the acid-leaching technology in part because Indonesia was mining the kind known as saprolite, which can be processed partly by using traditional smelters. But Indonesia — and the world — is running out of saprolite ore. What will be left is lower-grade limonite ore, which consists of less than 1.5 percent nickel, making processing by traditional means nearly impossible.

The decline in saprolite ore has occurred just as the demand for battery-grade nickel has spiked. Most nickel mined in Indonesia has previously gone into products like stainless steel, which can use a lower-grade mineral. But batteries require a higher standard, which has placed an unprecedented premium on the acid-leaching process.

TO CONTINUE READING Go to Original – washingtonpost.com

Tags: Chemical waste, Ecology, Electric Energy, Energy, Environment, Indonesia, Mining, Nickel, Pollution

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.