The Doctrine of ‘Just War’

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 28 Aug 2023

Prof. Johan Galtung – TRANSCEND Media Service

There is no scarcity of literature in this field, much of it permutations around the basic core of “I am of course against war, but – -”. So let it be clear from the outset that the present author is against war, there being no “but”. War as an institution to resolve conflict is an abomination, like slavery and colonialism as institutions. Occasional war, slavery and colonialism are probably hard to eliminate. But the key word is institution, legitimized by social norms and mores. A doctrine of just war is designed to do exactly that, offer a legitimation, for instance by seeing the evil of war as something that can be outweighed by possible positive consequences. But all human activity carries in its wake something good and something bad, weighing one against the other we can justify anything, like justifying Hitler with the Autobahnen. The just war doctrine is may be doing precisely that. The question is what kind of war, if any, that doctrine, reasonably applied, rules out as “unjust”?

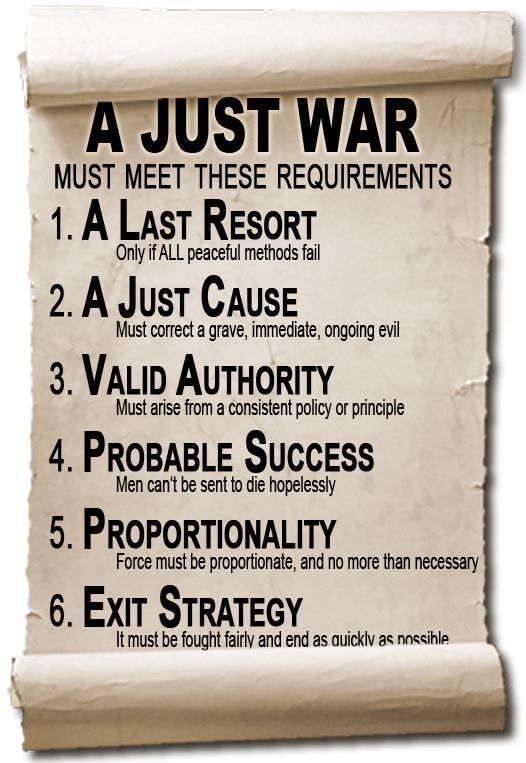

Let us first restate the six or seven principles, depending on how the classical Augustinian doctrine has been (re)stated:

- the authority launching the war must be legitimate;

- the war must be for a clearly just cause;

- all peaceful means of solving the problem have been tried;

- the good end must outweigh the bad means (war and aftermath);

- there must be a reasonable expectation of victory;

- the intention must be right, with no ulterior motives; and

- the methods of war must be legitimate.

All seven criteria are necessary conditions, none is sufficient.

There is much thinking behind the doctrine, giving it the air of something watertight. Only a very just war can possibly slip under a door so well designed to lock out all applicants lining up with their unjust war proposals. No doubt, there might be ways of applying the doctrine that would serve to eliminate most, if not all, wars. And it is not designed to eliminate all wars; the assumption is that the set of just wars is non-empty.

The seven rules can be divided into two groups: those that depend on the subjective judgment of the party about to launch the just war, and those that do not. Nos. [5] and [6] fall in the first category. The candidate can always claim that he expects victory; in fact it would be rather foolish not to do so. He can also claim that his motives are pure; again it would be rather foolish if he did not. And who are others to judge motives? Are their motives in doing so less impure than the impurity they are trying to uncover? A lie detector test, is that what is needed? But imagine that the just war candidate postulating for the international tribunal with his credentials is neither an impostor, nor a hypocrite nor a liar, but so self- righteous that he is not even capable of conceiving of himself as having anything than pure motives? In that case, and we might assume that to be a frequent case among candidates for positions as “just war”-wagers, there would be no way of verifying that the criterion is satisfied nor any way of falsifying the thesis. And the same goes for the highly subjective judgment of war outcomes. Such expectations may be challenged, but just war candidate may claim new weapons and tactics they cannot reveal lest the evil- doer gets to know. Besides, the challenger may be challenged: if you do not trust me, whose side are you on? Good or evil?

We are then down to five criteria, assuming that these two cannot be relied upon to eliminate anything. Let us no divide these five criteria into those that invoke legitimate authority and the others. Nos. [1] and [7] fall in the first category, the others in the second. In [1] there is reference to legitimate authority to undertake the war, in [7] to legitimate ways of waging the war. Iustus bellum; ad bello, in bellum.

The immediate problem is the legitimacy of the legitimate. To start with the legitimate means of waging the war: what is said is that a just war does not differ from other wars since all wars, including those that do not pass the other six tests, in principle have to be waged with legitimate means, in bellum, not only ad bello. A war not satisfying this principle is ruled out whether it is just or not; consequently satisfaction of the rule does not make the war more just. And the same applies to the legitimate authority: a war is a serious matter, one would assume under any circumstance wars to be undertaken only by authorities, and authorities normally do not see themselves as illegitimate.

But other may see them as illegitimate, and that would make the war objectively unjust even if the criterion does not work subjectively. Let us assume that only authorities can judge the legitimacy of authorities, not opposition groups. The legitimate authorities we talk about today are governments accountable to the people they serve, and the key organization of governments, the United Nations, accountable to governments it serves. Most governments, and the UN, envisage war-making as legitimate activity under some circumstances. Could it then be that the rules that make governments legitimate are biased in favor of belligerent activity by the strong rather than the weak?

An argument of that type would have to rest on high correlations between being strong and legitimate=democratic, or legitimate=veto power in the Security Council (since security matters are under the Security Council). If we combine economic and military strength the strongest countries in the world tend to be democratic=legitimate. For the Security Council the correlation is low, 3 out of 5 being democracies today. We do not need any theory for these correlations (maybe Protestantism was both entrepreneurial, aggressive and individualism?).

The point is that the criteria for legitimacy makes democracies that at the same time are capitalist and aggressive legitimate, meaning that when a war has to be evaluated they pass that criterion, their nondemocratic adversaries not, and given the structure of the world these two groups will often be in conflict. Saddam Hussein would probably base his legitimacy not on voting but being some incarnation of the Arab nation; a “criterion” not impressing democracies that in addition have veto power. Legitimacy becomes a needle’s eye only very big camels can get through, designed to keep out the smaller ones. And the same goes for the legitimacy in bellum, ruling out methods used by the weak (terrorism), but not methods used by the strong (state terrorism).

Conclusion: these two principles not only do not serve to exclude unjust wars but may even tilt the category of just war in favor of wars waged by the strong with the weapons of the strong. But it is hard to believe that justice tends to be on the side of the strong with random distribution of just causes and even harder to believe if we assume that both distributive and structural justice should tend to favor the weak and poor more than the strong and rich, on the average.

Let us then divide the remaining three rules in two categories: one rule, [3], that refers to facts (that all peaceful means shall have been exhausted), and [2] and [4] that refer to values; just cause and the means-end balance. At the first glance [3] looks like a very strong principle that can be used to exclude all wars, making the category of just wars empty. To demand that all peaceful measures should have been tried is to demand a lot since the set of “all peaceful measures” is unlimited. It is finite in a finite world (finite space, and we assume also finite time), but it is open; new candidates for inclusion as peaceful measures coming all the time. A pacifist predisposed against using violence would use this rule to say, “hey, wait a little, here is something else you can try – -”.

And the bellicist predisposed to use violence counters, “all possible methods were tried”, and bolsters this with four arguments very hard to falsify, meaning that the rule does not serve to rule out wars, just or non-just.

- First, he can deny that there are other peaceful measures to be undertaken, for instance by concealing negotiation offers from the other side, or ruling them out as “uninteresting”.

- Second, when challenged with a concrete non-belligerent proposal he can destroy the alternative through a generally hostile and threatening posture.

- Third, if the peaceful alternative nevertheless gets under way he can claim, often with some reason, that even peaceful methods, like economic sanctions work too slowly relative to the speed of the injustice.

- And finally, even if it does work he might claim that what is brought about by the peaceful means is not justice but its caricature, and that the evil forces behind the injustice are still there, and will recreate the injustice given a chance.

In short, there are enough ways of ruling out the negation of [3] as argument against launching the war. How about the last two, [2] and [4]? The problem is the same for both of them: we are dealing with utilities hard to quantify intersubjectively. But the relation between the two rules already carry the key to how to get around them. No. [2] defines the good in [4] as having unlimited positive utility, otherwise it would not have been an undoubted right, like the occupation of Kuwait. However, in that case the evils to be used in the war or produced by the war will also have to be unlimited to outweigh the right infringed. The pacifist would argue that this is the case. But the bellicist, and he is the only interesting one for the candidates will by definition have to be bellicists, would not.

Again the bellicist has many possibilities.

- First, he can operate militarily as if he is minimizing the damage, hitting only military and military targets, then using that as a cloak for much more extensive operations.

- Second, shorten the time perspective by looking only at short term negative consequences.

- Third, shorten the space perspective to consequences only at the point where he is operating.

- Fourth, shorten the functional perspective by comparing only military aspects, for instance weighing occupation against a war, not considering the total consequences, also political, for the civilian population.

In short, there are very many ways of maximizing the end utility and minimizing the means utility to arrive at the conclusion wanted: the cost-benefit analysis yields a positive difference, it is a Go! Including the technique of rejecting cost-benefit analysis, invoking the idea that “freedom is not to be bargained with; no sacrifice is too high”.

The reader acquainted with Gulf War history will recognize all these methods from the justification process. However, I would not use that as an argument against the “US-led coalition”, nor against Iraq/Saddam /Hussein using similar argumentation, the end with unlimited positive utility being the honor and self- respect of the Arab Nation. The basic problem is not whether the wars of 2 August 1990 and 17 January 1991 satisfied the rules, but whether the Augustinian code can serve as a guide at all or is only one more way of defining wars, almost any war, as an iustus bellum. Possibly there is such a thing. To operationalize it criteria are needed. But if these criteria exclude nothing as long as [2] is satisfied, and that is the only interesting case, then how can this be a guide? And if not, what does it mean, just war?

What it means in practice are a number of men, because the people doing such things with very serious faces and very trained minds, examining the “case”, are generally men, concluding [2]. Being part of [1] they then start engaging in [3] till will or imagination is exhausted, whatever comes first. Having done that they satisfy [5] by putting together invincible forces, then purify their minds and shorten the distance to divine forces by visiting churches, mosques and temples with chosen clergy so that [6] is satisfied and launch a war in such a way that they think [7] is satisfied.

How about [4], demanding some kind of proportionality? It is too imprecise, and too easily reduced to no criterion at all invoking the absolute nature of the right to be vindicated. What this means in practice is going ahead when the rest is satisfied, assuming that the proportionality then takes care of itself.

In short, and that is a crucial point: under the legitimacy given by conceiving of the war as just they become more, not less oblivious to the consequences. In practice this means that we are dealing with an ethic of intentions rather than of consequences, and that they would have done the same whether the number of casualties is 40, 400, 4000, 40.000 or 400.000 (possibly a close estimate) or 4.000.000 (only twice the Vietnam war casualties). This means that the logic is consequence-free; the conclusion is so robust that it survives any consequence. A single minded focus on intentions only is needed to make this an ethical conclusion.

In fact, it is reminiscent of the Inquisition. The same men with serious faces and impeccable deductive arguments from first principles and an undisputed evil: heresy. Then they went ahead, torturing and executing. In their mind there was no doubt that they were vindicating an undoubted right since the only true faith was threatened. Their credentials were impeccable and their methods entirely legitimate given the extreme threat. To attribute ulterior motives to such people was in itself a sign of heresy. From all pulpits would-be heretics had been given all warnings, “all peaceful means” had been tried. Given this they were entirely justified in using “all necessary means”, partly to restore the heretic to the true faith, partly to warn others.

Given this exercise the reader will have no difficulty constructing doctrines for “just slavery” and for “just colonialism”; all that is needed is an undisputed value threatened by the abolitionists, such as a nature-given master- servant relation between superior and inferior people(s). And this is what they did. Their successors were at work in the Gulf War. Applauded, like slavers and colonizers. Once upon a time.

__________________________________________

Johan Galtung, a professor of peace studies, dr hc mult, is founder of TRANSCEND International and rector of TRANSCEND Peace University. He was awarded among others the 1987 Right Livelihood Award, known as the Alternative Nobel Peace Prize. Galtung has mediated in over 150 conflicts in more than 150 countries, and written more than 170 books on peace and related issues, 96 as the sole author. More than 40 have been translated to other languages, including 50 Years-100 Peace and Conflict Perspectives published by TRANSCEND University Press. His book, Transcend and Transform, was translated to 25 languages. He has published more than 1700 articles and book chapters and over 500 Editorials for TRANSCEND Media Service. More information about Prof. Galtung and all of his publications can be found at transcend.org/galtung.

Johan Galtung, a professor of peace studies, dr hc mult, is founder of TRANSCEND International and rector of TRANSCEND Peace University. He was awarded among others the 1987 Right Livelihood Award, known as the Alternative Nobel Peace Prize. Galtung has mediated in over 150 conflicts in more than 150 countries, and written more than 170 books on peace and related issues, 96 as the sole author. More than 40 have been translated to other languages, including 50 Years-100 Peace and Conflict Perspectives published by TRANSCEND University Press. His book, Transcend and Transform, was translated to 25 languages. He has published more than 1700 articles and book chapters and over 500 Editorials for TRANSCEND Media Service. More information about Prof. Galtung and all of his publications can be found at transcend.org/galtung.

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER REMAINS POSTED FOR 2 WEEKS

Tags: Johan Galtung, Just War, Peace Research, St. Thomas Aquinas, Structural violence, Warfare

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 28 Aug 2023.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Doctrine of ‘Just War’, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

One Response to “The Doctrine of ‘Just War’”

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER:

The origins of the phrase are of course a kind of perversion — and certainly enabling of perversion. The same can be argued with respecct to “Just Suffering” — and the implied existence of a “Just Suffering Theory” yet to be explicitly articulated (https://www.laetusinpraesens.org/docs20s/dieoff.php#just)