How to Live in Light: A Blind Hero of the French Resistance on Seeing the Heart of Life and Contacting the Oneness of Being

INSPIRATIONAL, 18 Sep 2023

Maria Popova | The Marginalian – TRANSCEND Media Service

“To see takes time, like to have a friend takes time,” Georgia O’Keeffe wrote as she contemplated the art of seeing just before the Little Prince sighed his timeless sigh: “What is essential is invisible to the eye.”

“To see takes time, like to have a friend takes time,” Georgia O’Keeffe wrote as she contemplated the art of seeing just before the Little Prince sighed his timeless sigh: “What is essential is invisible to the eye.”

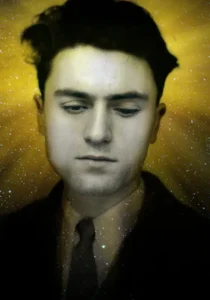

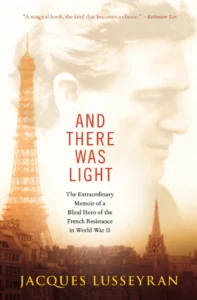

No one has written about what it takes to see — and how to do the looking — more poignantly than Jacques Lusseyran (September 19, 1924–July 27, 1971) in his stirring memoir And There Was Light (public library).

Looking back on his blissful early childhood, Lusseyran recounts his formative enchantment with the world:

Light cast a spell over me. I saw it everywhere I went and watched it by the hour… flowing over the surface of the houses in front of me and through the tunnel of the street to right and left. This light was not like the flow of water, but something more fleeting and numberless, for its source was everywhere. I liked seeing that the light came from nowhere in particular, but was an element just like air. We never ask ourselves where air comes from, for it is there and we are alive. With the sun it is the same thing.

There was no use my seeing the sun high up in the sky in its place in space at noon, since I was always searching for it elsewhere. I looked for it in the flickering of its beams, in the echo which, as a rule, we attribute only to sound, but which belongs to light in the same measure. Radiance multiplied, reflected itself from one window to the next, from a fragment of wall to cloud above. It entered into me, became part of me. I was eating sun.

Nightfall didn’t end the spell of the light, for he felt it in the very fabric of being:

Darkness, for me, was still light, but in a new form and a new rhythm. It was light at a slower pace. In other words, nothing in the world, not even what I saw inside myself with closed eyelids, was outside this great miracle of light.

And then, one May morning when he was seven, the light of the world went out — a classroom scuffle ended in a violent fall onto the corner of the teacher’s desk, leaving Lusseyran completely blind.

Somehow, he adapted, guided by the light within and by the discovery that the light without is a kind of vibration can we feel whenever we assume “the attitude of tender attention” — a vibration that reveals the world, its materiality and its mystery:

Objects do not stand at a given point, fixed there, confined in one form. They are alive, even the stones. What is more they vibrate and tremble. My fingers felt the pulsation distinctly, and if they failed to answer with a pulsation of their own, the fingers immediately became helpless and lost their sense of touch. But when they went toward things, in sympathetic vibration with them, they recognized them right away… Being blind I thought I should have to go out to meet things, but I found that they came to meet me instead.

In a passage evocative of Virginia Woolf’s transcendent epiphany about the oneness of the world, he adds:

If my fingers pressed the roundness of an apple, each one with a different weight, very soon I could not tell whether it was the apple or my fingers which were heavy. I didn’t even know whether I was touching it or it was touching me. As I became part of the apple, the apple became part of me. And that was how I came to understand the existence of things.

[…]

The reality — the oneness of the world — left me in the lurch, incapable of explaining it, because it seemed obvious. I could only repeat: “There is only one world. Things outside only exist if you go to meet them with everything you carry in yourself. As to the things inside, you will never see them well unless you allow those outside to enter in.”

Lusseyran was still a teenager when, unnerved by Hitler’s rise to power, he set out to teach himself German in order to understand the menacing radio broadcasts. In 1941, shortly after the Nazi invasion of France, he formed a resistance group and began publishing an underground newspaper that soon became the voice of the French freedom fighters. He was seventeen.

Two months before his nineteenth birthday, Lusseyran was betrayed by a member of the resistance, arrested by the Gestapo, and sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp. For six months, he was kept in “a space four feet long and three feet wide, with walls like a medieval fortress, door three fingers thick with a peephole through which the jailers watched day and night, and a sealed window.” But his bright spirit remained undimmed — devoted to stirring the spirit of resistance among the thousands of inmates, he came to see the place not as a prison but as “a church underground.” He would recount:

The mechanism of hope in our hearts must have a thousand springs, almost all of them unknown to us.

When liberation finally came two years later, Lusseyran was one of thirty inmates to leave the camp alive. Looking back on how he survived the unsurvivable, he returns to the lifeline of the light and the radiance of what the poet Muriel Rukeyser called “the living moment… in which we touch life and all the energy of the past and future.” Aliveness, he intimates, is a matter of our receptivity to light, which is the quality of attention we pay the world — no matter our circumstance:

When a ray of sunshine comes, open out, absorb it to the depths of your being. Never think that an hour earlier you were cold and that an hour later you will be cold again. Just enjoy. Latch on to the passing minute. Shut off the workings of memory and hope… Take away from suffering its double drumbeat of resonance, memory and fear. Suffering may persist, but already it is relieved by half. Throw yourself into each moment as if it were the only one that really existed.

And There Was Light is a remarkable read in its entirety. Complement it with Viktor Frankl, shortly after his release from the concentration camps, on life’s deepest source of meaning, then revisit Rebecca Elson’s poetic love letter to the light of the universe.

_______________________________________

My name is Maria Popova — a reader, a wonderer, and a lover of reality who makes sense of the world and herself through the essential inner dialogue that is the act of writing. The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first 15 years) is my one-woman labor of love, exploring what it means to live a decent, inspired, substantive life of purpose and gladness. Founded in 2006 as a weekly email to seven friends, eventually brought online and now included in the Library of Congress permanent web archive, it is a record of my own becoming as a person — intellectually, creatively, spiritually, poetically — drawn from my extended marginalia on the search for meaning across literature, science, art, philosophy, and the various other tendrils of human thought and feeling. A private inquiry irradiated by the ultimate question, the great quickening of wonderment that binds us all: What is all this? (More…)

My name is Maria Popova — a reader, a wonderer, and a lover of reality who makes sense of the world and herself through the essential inner dialogue that is the act of writing. The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first 15 years) is my one-woman labor of love, exploring what it means to live a decent, inspired, substantive life of purpose and gladness. Founded in 2006 as a weekly email to seven friends, eventually brought online and now included in the Library of Congress permanent web archive, it is a record of my own becoming as a person — intellectually, creatively, spiritually, poetically — drawn from my extended marginalia on the search for meaning across literature, science, art, philosophy, and the various other tendrils of human thought and feeling. A private inquiry irradiated by the ultimate question, the great quickening of wonderment that binds us all: What is all this? (More…)

Go to Original – themarginalian.org

Tags: Inspirational, Life, Philosophy, The Little Prince, Wisdom

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.