Jailhouse Rock had just come out and then rising star Elvis Presley was performing downtown. But he had not travelled there for rock music nor a typical birthday celebration. He had gone to give a speech at this elite event – campaigning for what was boldly described as a new, global ‘Capitalist Magna Carta’ to enshrine and protect worldwide ‘rights’ for private investors.

At a swanky hotel near the iconic Golden Gate Bridge, Abs presented his plan to more than 500 of the world’s most prominent bankers, businessmen and politicians gathering for what was called the International Industrial Development Conference.

He denounced “the well-known attitude of some less developed countries, according to which the Western world is actually obliged to pay for the advancement of their economies”. He instead proposed a new international legal system for the “effective and enforceable rule of law for private foreign investment”.

The context was the Cold War and rising independence movements in the South and labour movements in the North. Foreign firms who had profited under colonial regimes were feeling the earth shift beneath their feet.

Across Africa there were industries that could be nationalised by newly-freed nations, there were special concessions and vast landholdings that could be expropriated.

Foreign firms who had profited under colonial regimes were feeling the earth shift beneath their feet.

Abs said his proposed system could help respond to, or even prevent, such threats. It could also deal with what he called “indirect interferences with the rights of private foreign capital” – including states refusing to give up “essential raw materials” or grant companies required licences, and even “excessive taxation” (from the investors’ perspective).

What is now called the investor-state dispute settlement (or ISDS) is a powerful yet obscure global legal system through which multinational corporations can sue entire countries directly at shadowy international tribunals.

A similarly obscure branch of the World Bank called the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) has overseen the bulk of such cases —- almost 1,000 in total as of September 2023, with almost 300 still pending.

Challenging policies

Some of these disputes have been worth billions of dollars – and have challenged laws and policies including environmental regulations, as well as post-apartheid black economic empowerment policies in South Africa.

Widespread popular opposition to this system’s inclusion in the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), proposed between the US and the European Union, helped lead to the treaty’s downfall in 2016.

Yet few of the cases that have gone through this system have been covered, let alone investigated, by journalists. They have had, and are still have, significant impacts on taxpayers, voters and residents of countries around the world – largely in the shadows.

Shortly after we began as fellows at the Centre for Investigative Journalism in London, in 2014, we received an unexpected phone call that sent us to El Salvador and into this ISDS system.

From the frontlines of local struggles against mining in that country to the archives of the World Bank’s ICSID centre in Washington DC, we traced how this system has been used by multinational corporations and foreign investors to challenge environmental regulations and people’s movements around the world – and how it was set up for such purposes.

Rather than a system initially created with good intentions, historical documents showed us how it was set up anti-democratically, against concerns from developing countries.

“The World Bank was concerned that different strands of resistance would unite.”

ICSID was established in 1966. Ahead of that, the World Bank held regional meetings about it – summary notes from which showed how some developing countries had objected to the proposal’s substance and form, from the start.

It would give foreign investors a “privileged position, in violation of the principle of full equality”, warned a Brazilian delegate. An Indian representative at another meeting said that it would give “investors additional rights of unspecified scope”, without saying anything about their obligations – and that draft proposals should “be considered in a wider forum” before being adopted.

According to British academic Taylor St John, who also studied this period, there was an extensive Bank strategy “to avoid opposition uniting”. She said: “The Bank was concerned that different strands of resistance would unite”, particularly after previous attempts to set up such a system through the OECD or UN had ended in stalemates. She described how it adopted a range of tactics to prevent this, including not circulating notes from consultations on its proposals.

However other historic documents showed that other people had pitched the idea, and welcomed it – including years before the World Bank took it up. Rather than representing the people, they came from the transnational corporate elite.

San Francisco, 1957

We found another extraordinary window into the creation of the ISDS system in TIME magazine’s archives. In the late 1950s, Henry Luce, the American magazine magnate, and publisher of Time, Life, and Fortune, started funding what was called the International Industrial Development Conference (IIDC).

The 1957 edition was held in San Francisco – where Hermann Abs made his pitch for what TIME dubbed a “Capitalist Magna Carta” and described as “the most widely applauded concrete proposal of the conference”.

The TIME-LIFE International media group co-sponsored that event and TIME published an illustrated, eight-page supplement to it, entitled “The Capitalist Challenge”. Its colourful articles described attendees as “an international Who’s Who of high finance and high office”.

It said: “From London came financiers whose firms had bankrolled the Industrial Revolution; from Berlin the brisk businessmen who have built Europe’s sturdiest economy from the rubble of war”. The Italian car giant Fiat’s managing director was there. But the biggest delegation was a “202-man phalanx of US executives” including from Ritz Crackers and RCA electronics.

The context – of corporate elites’ fears that people’s movements could threaten them – is also clearly presented in these articles. One described how “Westerners emphasised the need to protect investors in new lands seething with nationalism.”

Another on ‘The Anti-Capitalist Attitude’ said “one of the biggest barriers in the way of foreign investment in the world’s underdeveloped countries” lies in the “minds and emotions of those who need foreign investment most…because they often tend to equate it with 19th century-style colonialism, they are reluctant to accept it”.

“Westerners emphasised the need to protect investors in new lands seething with nationalism.”

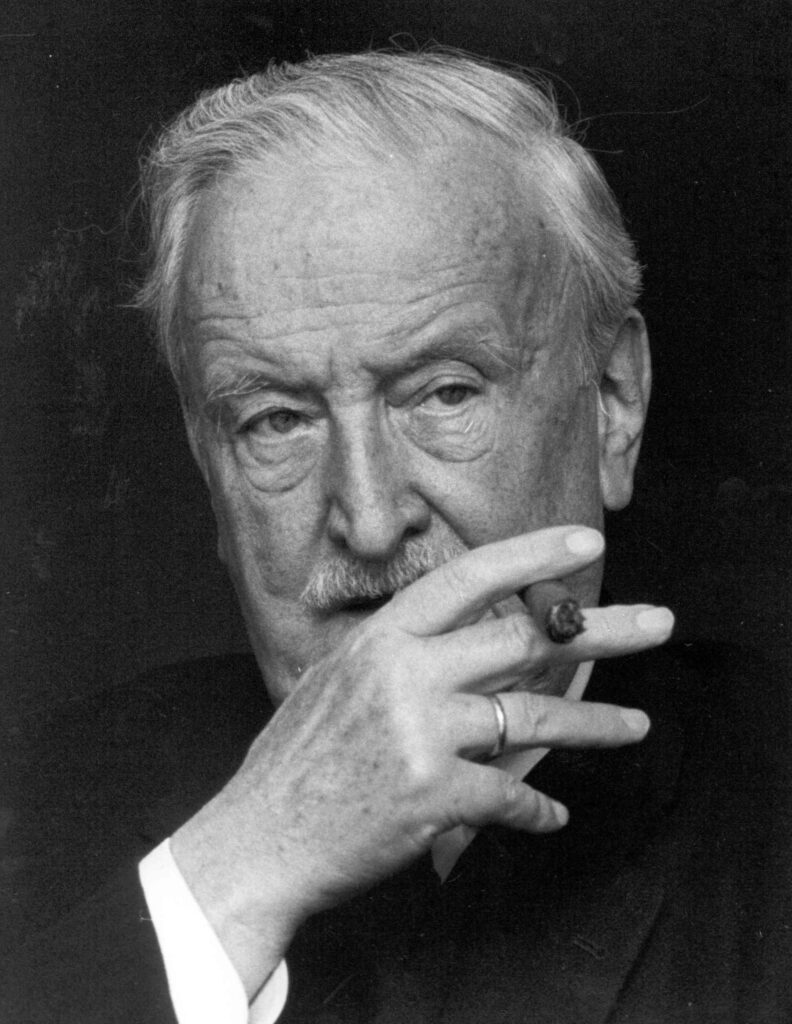

By then, Abs was already a legend in the world of international finance. “His appointment in 1937 as head of the Deutsche Bank’s foreign department established him at 36 as the Wunderkind of German banking,” TIME would later write about him, describing how he would also join the boards of directors of 25 large corporations and be so busy that “much of his decision making is done on airplane flights”.

When he died in 1994, the late Eric Roll, Baron of Ipsden, and former director of the Bank of England, wrote an obituary for the UK newspaper The Independent which called Abs “the outstanding German banker of his time”.

It described him as an advisor to Indonesia, the Holy See, Argentina, Brazil, and the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC), which lends and invests money directly in private companies.

Roll also shared a joke about the banker: upon arriving in heaven, he finds it dilapidated and in financial ruin. Abs quickly draws up a plan for the archangels: Heaven plc – the privatisation of the afterlife, with the Almighty as Deputy Chairman of the Board. (The implication: Abs himself would be Chairman, above God).

The plan

In San Francisco, Abs – who was additionally chair of a group called the German Society to Advance the Protection of Foreign Investments — told his audience that lawyers were already working out the details of his plan, and that he hoped that a draft of his proposed convention would be ready to share with allies by the end of the year.

The banker’s California trip was just one stop on an international campaign trail, promoting this new global legal system to protect foreign investors’ interests.

There were some informal precedents for his proposal. In 1864, Napoleon III arbitrated a dispute between the Suez Canal Company and the state of Egypt. In that case, the company had demanded compensation from the country for cancelling a canal construction project over its use of forced labour. The assembled tribunal sided with the company, deferring to what it called the “sanctity” of the contract, and ordering Egypt to pay a massive penalty.

Reviewing this “long forgotten” dispute, US law professor Jason Yackee wrote in 2015 that the company’s claim had “a strikingly modern (and perhaps even timeless) character: under what circumstances, and with what consequences, can the government of the day change its laws in order to promote its conception of the public good, where the change negatively impacts, and perhaps even destroys, the value of the foreigner’s investments?”

In 1864, Napoleon III arbitrated a dispute between the Suez Canal Company and the state of Egypt.

Back then, such cases were on ad-hoc bases, without an institutional infrastructure. This is what Abs was proposing to change. In late 1957, just a few months after the San Francisco conference, he released, as promised, a draft “International Convention for the Mutual Protection of Private Property Rights in Foreign Countries”.

In 1958, a separate group of lawyers led by Lord Hartley Shawcross, a former attorney general in the UK and a director of Shell, produced a second draft “Convention on Foreign Investments.” In 1959, these two proposals were merged and reissued as a single draft known as the “Abs/Shawcross Convention on Investment Abroad,” which the West German government submitted to what is now the OECD.

The same year, an all-party parliamentary commission in the UK published a report calling for a world investment convention and an arbitral tribunal to settle disputes.

Their idea didn’t go too far however, until the idea found a new home at the World Bank, itself increasingly involved in expanding private business globally.

The “Banker-Diplomat”

Eugene Black, then President of the World Bank, had also spoken at the San Francisco event, condemning a “hostile attitude, by governments and peoples alike, toward the profit motive”. He insisted that “people must come to accept private enterprise, not as a necessary evil, but as an affirmative good” – while governments must do more than ‘tolerate’ private business. He clarified: “They must welcome its contribution and go out of their way to attract it and even to woo it.”

Born in 1898 in Atlanta, Georgia, Black had come from an elite family of bankers. In the 1930s, his father had briefly been chairman of the US Federal Reserve. He arrived at the World Bank in the late 1940s after working at an investment firm and Chase National Bank, and soon “came to personify the Bank”, according to the institution’s account of his tenure, when it “became widely known as Black’s Bank”.

It remembers him as a “Banker-Diplomat” who was – echoing his comments in San Francisco – “deeply concerned about communism spreading and its impact on the restoration of a functioning global, capitalist economy”.

With Black at its helm, the World Bank expanded rapidly. It lent increasing amounts of money to governments around the world – and set up new branches to directly support private companies. He had a “knack for bargaining and negotiating”, wrote a bank historian in the 1990s, describing his “international reputation as a mediator” and how he had been “influential in settling foreign investment disputes” – insisting that countries come to the table with companies to negotiate deals.

“People must come to accept private enterprise, not as a necessary evil, but as an affirmative good.”

Along with the German (Abs), the Englishman (Shawcross) and this American (Black), two other men seemed to play particularly pivotal roles in the creation of the international investor-state legal system we had been investigating.

One was another American – George D. Woods, who took over as World Bank president when Black retired in 1963. Like Black, he’d been a commercial banker first. In his first address to the World Bank’s board, as its new president, he pledged to explore “all possible ways in which the Bank can help to widen and deepen the flow of private capital to the developing countries”. He said that he was convinced that countries which accept this “will achieve their development objectives more rapidly than those who do not” –– and stated “that means, to mince no words about it, giving foreign investors a fair opportunity to make attractive profits”.

The second was Aron Broches. He had been part of the official Dutch delegation at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, at which the World Bank, along with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were created. Then, he served as the Bank’s general counsel for decades. In the 1960s, he oversaw the creation of ICSID.

Enshrining the system

Over the next several decades, the ISDS system was enshrined in thousands of international treaties that grant foreign investors access to it in case of disputes with governments. They effectively give the state’s advance “consent” for foreign investors to file claims at places like ICSID.

Broches would himself become very involved in these deals – encouraging states to sign what were called Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) with other countries, including such provisions.

For a long time, almost all of these cases were filed by companies based in rich countries, against governments in poor countries. This seemed to match the vision of this system’s creators, and the enduring rhetoric of how it should help poor countries to develop by increasing amounts of foreign investment. However, more recently, there had been a spike in cases against rich countries too – including Abs’ Germany.

We saw in ICSID’s case database that a pair of suits had been filed against Germany, by a Swedish company. One was worth billions and was ongoing, over the country’s decision to close down its nuclear power plants. The second was about a controversial new coal-fired power plant that seemed to contradict Germany’s much-lauded promises to pursue an epic ‘green energy’ transition.

If Germany – sometimes called the ‘grandfather’ of the international investor-state legal system – could be sued, it seemed like any country, and thus every taxpayer and citizen, globally could be at risk. We thought again of questions that had driven us thus far. Were our elected officials actually in charge of as much as they said?

______________________________________________

Claire Provost is co-founder and co-director of the non-profit Institute for Journalism and Social Change. She is the co-author of Silent Coup (2023).

Claire Provost is co-founder and co-director of the non-profit Institute for Journalism and Social Change. She is the co-author of Silent Coup (2023).

Matt Kennard is chief investigator at Declassified UK. He was a fellow and then director at the Centre for Investigative Journalism in London.

Matt Kennard is chief investigator at Declassified UK. He was a fellow and then director at the Centre for Investigative Journalism in London.

This is an adapted extract of Silent Coup: How Corporations Overthrew Democracy by Claire Provost and Matt Kennard (Bloomsbury Academic 2023)