The Destruction of Palestine Is the Destruction of the Earth

SPOTLIGHT, 15 Apr 2024

Andreas Malm | Verso Books - TRANSCEND Media Service

The last six months of genocide in Gaza have ushered in a new phase in a long history of colonization and extraction that reaches back to the nineteenth century. A true understanding of the present crisis requires a longue durée analysis of Palestine’s subjugation to fossil empire.

8 Apr 2024 – So we are now clocking half a year of this genocide. Half a year has passed since the resistance launched Toufan al-Aqsa and the occupation responded by declaring and executing genocide. It’s been half a year, six months, 184 days of bombs picking off one family after another, one high-rise building after another, one residential district after another, relentlessly, methodically: half a year of the grey bones of children poking out under the rubble, of rows of tiny white body bags lined up on the ground, of a mutilated girl hanging from a window as a from a meat hook; half a year of parents bidding farewell to their children with eery composure, as if their spirits have left them empty and blank, or in uncontrollable spasms of grief, as if they don’t know how to ever again put one foot in front of the other and take a step on this Earth; half a year of a dozen massacres per day, summary executions, sniping, driving over the corpses with bulldozers and all the rest and it just doesn’t stop, it goes on and it goes on and it doesn’t stop and then it continues and proceeds apace and it won’t come to an end and it just doesn’t stop. One can go insane with despair watching this from a distance. If one feels that way, then one should try to imagine how the people feel who are still alive in Gaza.

*

One component of the definition of genocide is the ‘physical destruction in whole or in part’ of the targeted group of people; and in Gaza, a central category is precisely that of physical destruction. Already in the two first months, Gaza was subjected to utter and complete destruction. Already before the end of December, the Wall Street Journal reported that the destruction of Gaza equalled or surpassed that of Dresden and other German cities during the Second World War. One of the bravest voices outside of Palestine is Francesca Albanese, the UN Special Rapporteur on the territories occupied in 1967. She begins her recent report with the observation that ‘After five months of military operations, Israel has destroyed Gaza’, before going on to detail how every foundation of life in Gaza has been ‘completely sacked.’[1] The emblematic image is that of a house smashed into pieces and survivors frantically digging through the rubble. If they are lucky, a boy or a girl all covered in dust might be pulled out from the mass of debris. The estimate now is that some 12,000 dead bodies remain to be extracted from the pulverised houses of Gaza.

While it has never before approached the scale we are now seeing, this is not exactly the first time the Palestinians have experienced this sort of thing. The script can be found in the 1948 Plan Dalet, where Zionist forces were instructed in the art of ‘destroying villages (by setting fire to them, by blowing them up, and by planting mines in their rubble)’. [2] During the Nakba, it was commonplace for these forces to invade a village during the night and systematically dynamite one house after another with families still inside them.[3] A peculiarity of the Palestinian experience is that this has never come to an end. The original act of destroying the houses over the heads of their inhabitants is repeated again and again: in al-Majdal in 1950, from which the people were deported to Gaza; in Gaza in 2024; and in between, any number of eternal. To pick just one: Beirut in 1982, described by Liyana Badr in A Balcony over the Fakihani, with words that could fit any other instantiation:

I saw piles of concrete, stones, torn clothes scattered about, shattered glass, little pieces of cotton wool, fragments of metal, buildings destroyed or leaning crazily (…) White dust smothered the district, and through the gray of the smoke loomed the gutted shells of blocks and the debris of houses razed to the earth. (…) Everything there was mixed up together. Cars were upside down, papers whirling in the sky. Fire. And smoke. The end of the world.[4]

This is the end of the world that never ends: fresh rubble is always poured out over the Palestinians. Destruction is the constitutive experience of Palestinian life because the essence of the Zionist project is the destruction of Palestine.

This time, unlike in 1948 or 1950, however, the destruction of Palestine is playing out against the backdrop of a different, but related process of destruction: namely, that of the climate system of this planet. Climate breakdown is the process of ecosystems being physically destroyed, from the Arctic to Australia. In our book The Long Heat: Climate Politics When It’s Too Late, forthcoming from Verso in 2025, my colleague Wim Carton and I discuss in some detail how rapidly this process is now unfolding. To take but one example, the Amazon is caught up in a spiral of dieback that might end with it becoming a treeless savanna. The Amazon rainforest has been standing for 65 million years. Now, in the span of a few short decades, global warming – together with deforestation, the original form of ecological destruction – is pushing the Amazon towards the tipping point beyond which it would cease to exist. Indeed, as I write, much recent research suggests that it is perched on that point.[5] If the Amazon were to lose its forest cover – a dizzying thought, but entirely within the realm of a possible near future – it would be a different kind of Nakba. The immediate victims would, of course, be the indigenous and afrodescendent and other people of the Amazon, some 40 million in all, who would, in the most likely scenario, see fires rip through their forest and turn it into smoke and so live through the end of a world.

Sometimes, this process takes on a remarkable morphological similarity to the events in Gaza, even in geographical proximity. On the night of 11 September last year, less than a month before the start of the genocide, Storm Daniel hit Libya. In the eastern city of Derna, on the shores of the Mediterranean, about 1000 km from Gaza, people were killed in their sleep. Suddenly a force from the sky destroyed their homes on top of them. Afterwards, reports described how random furniture and body parts poked up through pulverised buildings. ‘Corpses still litter the street, and drinkable water is in short supply. The storm has killed whole families’. According to one native of the town, it was ‘a catastrophe unlike anything we have ever seen. The residents are searching for the bodies of their loved ones by digging with their hands and simple agricultural tools’. There were Palestinian first responders rushing to the scene; according to one of them: ‘the devastation is beyond all imagination (…) You walk through the city and see nothing but mud, silt and demolished houses. The smell of corpses is everywhere. (…) Entire families have been erased from the civil registry. (…) You see death everywhere.’

During its 24-hour visit, Storm Daniel dropped a load of water – around 70 times larger than the average amount for the month of September. Derna was located at the mouth of a river, running through a wadi towards the sea, normally within narrow banks, if indeed it ran at all. This was desert country. But now suddenly the river rose, burst through two dams and crashed into Derna, the water, sediment, debris forming a bulldozer that ripped and roared through the city in the middle of the night to 11 September – a force of such speed and violence as to drive structures and streets into the Mediterranean and turn the former centre into a brownish, muddy bog. Using today’s refined methodologies of weather attribution, researchers could quickly conclude that the floods had been made fifty times more likely by the global warming experienced so far – mathematical code for the cause of the disaster. Only this warming could have brought about that event. During the preceding summer months, the waters off North Africa had been no less than five and a half degrees warmer than the average from the previous two decades. And warm water holds heat energy that can get packed into a storm like fuel into a missile. Some 11,300 people were killed in one single night by Storm Daniel in Libya – the most intense event of mass killing by climate change so far in the decade, possibly the century.

These scenes formed a striking prefiguration of those that would begin to play out in Gaza 26 days later; but there were also direct connections between the places. Because rescue teams in Gaza have long been used to dealing with this kind of destruction, they moved swiftly into Derna to help out. At least a dozen Palestinians who had fled from Gaza to Derna were killed in the floods. One Palestinian, Fayez Abu Amra, told Reuters: ‘Two catastrophes took place, the catastrophe of the displacement and the storm in Libya’ – the Arabic word for catastrophe here, of course, being Nakba. So according to Fayez Abu Amra, the first Nakba was the one of 1948, which drove his family and 800,000 other Palestinians out of their homeland; his family ended up in mukhayam Deir al-Balah, and then some members moved on to get away from the Israeli wars of aggression, to the town of Derna; and then came a second Nakba. Fayez Abu Amra lost several relatives in the storm. He himself survived, because he had chosen to stay behind in Deir al-Balah, where mourning tents were erected for the victims. And then came, just a few weeks later, the genocide. God knows if Fayez Abu Amra is still alive.

Now, as we recognise the similarities and entanglements of these processes of destruction, some significant differences also strike the eye. The forces that bombed Derna were of another nature than those bombing Gaza. The anonymous sower of death from the sky in the former case was not an air force, but the cumulative saturation of the atmosphere with carbon dioxide. No one had the specific intention to destroy Derna, like the state of Israel has had the express intention to destroy Gaza; there were no army spokesmen announcing the focus on ‘maximum damage’, no Likud MP howling ‘Bring down buildings!! Bomb without distinction!!’ When fossil fuel companies extract their goods and put them up for combustion, they do not intend to kill anyone in particular. They know, however, that these commodities will, as a matter of certainty, kill people – it might be people in Libya, or in Congo, or in Bangladesh, or in Peru; it is of no consequence to them.

This is not genocide. In our book, Overshoot: How the World Surrendered to Climate Breakdown, which will be published by Verso in October this year, Wim and I toy with the term paupericide for what is going on here: the relentless expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure beyond all boundaries for a liveable planet. The initial purpose of the act per se is not to kill anyone. The goal of extracting coal or oil or gas is to make money. Once it becomes fully established that this form of money-making actually kills multitudes, however, the absence of intention begins to fill up. As a corollary of the basic insights of climate science, the knowledge is now more or less universally spread: fossil fuels kill people, randomly, blindly, indiscriminately, with a heavy concentration on poor people in the global South; and they kill in greater numbers the longer business-as-usual continues. When the atmosphere is oversaturated with CO2, the lethality of any additional quantum of CO2 is high and on the rise. Mass casualties are then an ideologically and mentally processed, de facto accepted result of capital accumulation. ‘If you’re doing something that hurts somebody, and you know it, you’re doing it on purpose’, prosecutor Steve Schleicher said in his closing argument against Derek Chauvin, later convicted for the murder of George Floyd; mutatis mutandis, the same applies here. Indeed, the violence of fossil fuel production becomes more lethal and more purposeful for every passing year. Now compare this with one bombing in mukhayam Jabaliya on 25 October, which killed at least 126 civilians, including 69 children. The stated purpose of this act was the killing of a single Hamas commander. Did the occupation intend to also kill the 126 civilians, or was it just callously indifferent to that kind of mass collateral damage? Intentionality and indifference blur here. So, too, on the climate front – still qualitatively different from that of Palestine; but perhaps the difference is diminishing.

Are there any specific moments of articulation between the destruction of Palestine and the destruction of the Earth? By moments of articulation, I mean points where one process impacts and forms the other, in a reciprocating causation, a dialectic of determination. My answer is yes, indeed, such moments of articulation have linked up in a rather tight sequence for almost two centuries now. Because I am a history nerd, I will go back to the moment when it began: 1840. The events of that year have been a perennial obsession of mine. I have touched upon them here and there, but I have yet to write a coherent account. I began doing this research eleven years ago, towards the end of my PhD, when I wrote Fossil Capital and realised that the topic required a study of its own, a sequel to be called Fossil Empire. In the past weeks, I have returned again to this moment in time with a view to developing a longue durée analysis of fossil empire in Palestine.

*

1840 was a pivotal year in history, for both the Middle East and the climate system. It marked the first time the British Empire deployed steamboats in a major war. Steam-power was the technology through which dependence on fossil fuels came into being: steam-engines ran on coal, and it was their diffusion through the industries of Britain that turned this into the first fossil economy. But steam-power would never have made an imprint on the climate if it had stayed inside the British Isles. Only by exporting it to the rest of the world and drawing humanity into the spiral of large-scale fossil fuel combustion did Britain change the fate of this planet: the globalisation of steam was a necessary ignition. The key to this ignition, in turn, was the deployment of steamboats in war. It was through the projection of violence that Britain integrated other countries into the strange kind of economy it had created – by turning fossil capital, we might say, into fossil empire.

At this time, Britain was the largest empire the world had ever seen, built on naval supremacy, hitherto founded on the traditional motive power of wind. But in the 1820s, the Royal Navy began to consider steam propulsion – burning coal, that is, instead of sailing with the wind; wind being a ‘renewable’ source as we would call it today, inexhaustible, cheap, indeed free of cost, but with well-known limitations. The captains could not take for granted that it blew as they wished it to. On the battlefield, ships might be held back by calms, or driven away from their targets by gusts and gales in the wrong direction, or allowed to advance only slowly. Freaks of the wind could give the enemy opportunities to slip away, regroup, hit back. In military action, when the mobilisation of energy was most urgently needed, wind was an unreliable force. Steam obeyed another logic. It derived its force from a source of energy that had no relation to the weather conditions, the winds, currents, waves, tides: coal came from the stock underground, a legacy of photosynthesis hundreds of millions of years old, and once brought above ground, it could be burnt at whatever point and whatever moment the owner demanded. The striking force of a steamer could be summoned at will. A fleet of such vessels could be arranged just as the captains wanted it – cannons pointed, troops landed, enemies chased down no matter how the wind blew. Such freedoms were particularly stressed by admiral Charles Napier, the most energetic champion of steam in the Royal Navy, who summed them up pithily: ‘steamers make the wind always fair’; or, ‘steam has gained such a complete conquest over the elements, it appears to me that we are now in possession of all that was required to make maritime war perfect’.[6] The conquest of the elements was, ultimately, a function of the spatio-temporal profile of fossil fuels: because of their detachment from space and time on the surface of the Earth, they promised to liberate the empire from the coordinates in which boats had navigated since time immemorial.

The first time Napier got to practise this perfection was in 1840, right here, on the shores of Lebanon and Palestine. In that year, Britain went to war against Muhammed Ali. Ali was the pasha of Egypt, nominally serving under the Ottoman Empire but in practise the ruler of his own realm, which, by now, was in a state of war with the sultan. Ali’s forces had fanned out from Egypt and conquered the Hijaz and the Levant and formed an Arab proto-empire, on a collision course with the Porte and with London. Ali’s rise threatened to bring down the Ottoman Empire, whose stability and integrity Britain, at this point in time, regarded as a strategic asset against Russia. If the Ottoman Empire disintegrated, Russia might expand south and east towards the crown colony of India, so Britain wanted to prop it up. Inter-imperialist rivalry, we might say, prompted Britain to intervene against Ali. So did, no less importantly, the dynamics of capitalist development inside Britain itself. The cotton industry was its spearhead, but in the 1830s, it had run so far ahead of every other branch as to suffer a crisis of overproduction: there were too large mountains of cotton thread and fabric coming out of the factories. Sources of demand were insufficient to absorb them all. Britain was, therefore, desperate for export markets; and thankfully, in 1838, the Ottoman Empire agreed to a fabulously advantageous free trade agreement, known as the Balta Liman treaty. This would open the territories under the sultan’s control to essentially unlimited British exports. The problem, however, was that ever more of these territories were passing into the control of Muhammed Ali, who pursued the opposite economic policy: import substitution. He built his own cotton factories in Egypt. By the late 1830s, they had grown into the largest industry of its kind outside Europe and the US. Ali would have none of the British free trade: he put in place tariffs and monopolies and other protective barriers around his cotton industry and promoted it so effectively that it could make incursions into markets hitherto dominated by Britain, as far away as in India itself.

Britain hated it. And no one hated it with more fervour than Lord Palmerston, the foreign secretary and chief architect of the British Empire in the middle of the nineteenth century. He would blurt out: ‘the best thing Mehemet could do would be to destroy all his manufactures and throw his machinery into the Nile.’[7] He and the rest of the British government considered Ali’s refusal to accept the Balta Liman treaty a casus belli. Free trade had to be forced onto Ali and all the Arab lands he ruled. Otherwise the British cotton industry would remain suffocated, without the outlets it needed to keep expanding, potentially choked even further by this Egyptian upstart. Lord Palmerston did not conceal his foreign policy principles. ‘It was the duty of the Government to open new channels for the commerce of the country’; his ‘great object’ in ‘every quarter of the world’ was to prise open lands for trade, and this committed him to an all-out confrontation with Ali.[8] He became obsessed with ‘the Eastern question’. ‘For my own part, I hate Mehemet Ali, whom I consider as nothing but an arrogant barbarian’, Palmerston wrote in 1839: ‘I look upon his boasted civilization of Egypt as the arrantest humbug.’[9] London grew more belligerent by the month. ‘Know’, the consul-general in Alexandria warned the pasha, ‘it is in the power of England to pulverize you.’[10] ‘We must strike at once rapidly and well’, Lord Ponsonby, the ambassador in Istanbul, sent home his advice, and ‘the whole tottering fabric of what is ridiculously called the Arab Nationality will tumble to pieces.’[11] With such words ringing through the corridors of Whitehall, Lord Palmerston ordered the Royal Navy to collect its best steamboats. In the late summer of 1840, a state-of-the-art squadron under the command of Napier set off towards the town of Beirut.

*

Napier’s favourite vessel was called the Gorgon. Propelled by a 350 horsepower steam-engine, with room for 380 tons of coal, 1,600 soldiers and six guns, it was ‘the first true fighting steamship’, marking ‘a new era’.[12] Napier took the Gorgon to reconnoitre the area around Beirut, running up and down the coast as he saw fit, in splendid disregard of the weather – but he did send out a pressing request to his fellow officers: ‘you must send me coal vessels here at all costs, because steamers without coal are useless.’[13] On 9 September, the bombardment of Beirut commenced. Gorgon and three other steamers took the lead, a further 15 sailing-ships arrayed around them. Their funnels spewing smoke, the steamers had a distinctive ability to circle the bay of Beirut back and forth and harass the Egyptian defenders, commanded by Ali’s son Ibrahim Pasha. Other targets appear to have been hit as well. After a day of particularly severe shelling, on 11 September, the local general sent a letter of accusation to the British fleet:

For the sake of killing five of my soldiers, you have ruined and brought families into desolation; you have killed women, a tender infant and its mother, an old man, two unfortunate peasants, and doubtless, many others whose names have not yet reached me (…) Your fire, I say, became more vigorous and destructive for the unfortunate peasants rather than for my soldiers. You appear decided to make yourselves masters of the town.[14]

Some sources from within Beirut claimed that around 1,000 people were killed in the bombardment, their bodies strewn about the streets. The crew on a US cruiser reported that ‘all the buildings, both private and public, were in a heap of ruins, the English fleet were firing upon the few buildings remaining, and were determined not to leave one stone upon another, and the town presents a scene of havoc and destruction.’[15]

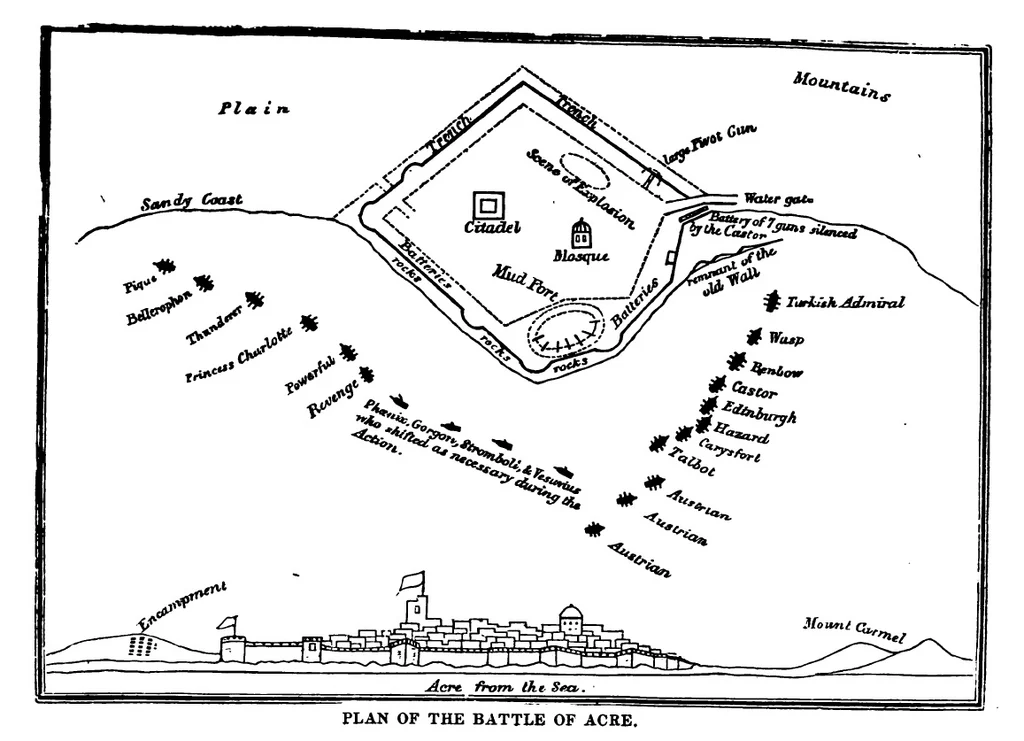

After this feat, the steamers chased Ibrahim Pasha’s troops along the coast. From Latakia in the north via Trablus and Sur to Haifa in the south, their positions fell like domines, the defenders withdrawing under the relentless, unpredictable attacks. ‘Steam gives us a great superiority, and we shall keep them moving’, Napier exulted: ‘Ibrahim must march very quick if he could beat steam’.[16] A gratified Lord Palmerston followed the news from the frontline, rapidly dispatched with steam packets to London, and wrote back: ‘The more force can be accumulated in Syria the better.’[17] Next he ordered an attack on the Palestinian town of Akka. Everyone knew that the decisive battle would stand there. Akka had, famously, held out for half a year against Napoleon in 1799, and then again for half a year in 1831, when Ibrahim Pasha laid siege to it. Since then, the Egyptians had repaired the walls of the old crusader capital, armed its ramparts with heavy guns and garrisoned it with thousands of troops, reinforcing the standing of Akka as by far the sturdiest fortress on the Levantine coast. A major depot, it was filled to the brim with weapons and ammunitions, most of them in a central magazine. It was also a thriving town with a civilian population that had nothing to do with military affairs.

On 1 November 1840, Gorgon and the other three steamers appeared in front of Akka. They were alone; the sailing ships had been delayed by light winds. Napier called on the Egyptians to surrender. When they refused, the bombarding began. One report described the action:

The service of steam-ships in war was thus shewn: the steam division of the Allies having arrived in the Bay, immediately commenced throwing shot and shells into the town, which must have annoyed the garrison very much; as, although they returned a very brisk fire, from the steamers constantly shifting their positions, it was harmless.[18]

On the evening of 2 November, the wind-powered remainder of the fleet arrived. A proper line of battle was arranged. The special mobility of the new mode of propulsion would be fully utilised, the steamers forming the central prong of the assault:

The dreadful crash was heard far above the tumult of the assault, and was immediately succeeded by a most awful pause. The firing on both sides was suddenly suspended, and for a few minutes nothing broke the fearful silence but the echoes of the mountains repeating the sound like the rumbling of distant thunder, and the occasional fall of some tottering building.’[20]

Akka’s great powder magazine had been hit by a shell. Gorgon was dubbed the hero of the strike. In the confident words of one British captain, the ‘magazine blew up in consequence of a well directed shell from the “Gorgon” steam-frigate.’[21] We cannot rule out that it was an accidental hit, but the British were clearly aware of the position of the magazine. Relaying fresh intelligence, Lord Minto, the highest commander of the Royal Navy, informed the command on the ground that ‘there is much powder stored about very insecurely at Acre’ and pointed it out as a suitable target, in a letter signed on 7 October.[22]

Whatever the exact degree of intentionality, the results of the strike from the first true fighting steamship are not in doubt. The Palestinian town of Akka turned into a mass of rubble. ‘Two entire regiments’, said a report to Lord Palmerston, ‘were annihilated, and every living creature within the area of 60,000 square yards ceased to exist; the loss of life being variously computed from 1,200 to 2000 persons.’[23] As night fell on 3 November, the few surviving Arab soldiers evacuated their last positions in Akka. When the British troops entered the town the next day, they were greeted by utter devastation. Here is one portrait:

Corpses of men, women, and children, blackened by the explosion of the magazine, and mutilated, in the most horrid manner, by the cannon shot, lay every where about, half buried among the ruins of the homes and fortifications: women were searching for the bodies of their husbands, children for their fathers.[24]

In a letter home to his wife, Charles Napier himself expressed unease and perhaps a pang of guilt. ‘I went on shore at Acre to see the havoc we have occasioned, and witnessed a sight that never can be effaced from my memory, and makes me at this time even almost shudder to think of it.’ He saw hundreds of dead and dying lying in the ruins; ‘the beach for half a mile on each side was strewed with bodies’; after some days, the corpses ‘infected the air with an effluvium that was truly horrid.’[25] Even in his official account of the War in Syria, Napier admitted that ‘nothing could be more shocking than to see the miserable wretches, sick and wounded, in all parts of this devoted town, which was almost entirely pulverized.’[26] The British seemed taken aback by the scale of the destruction they had wrought. In a letter to Lord Minto, another admiral wrote: ‘I cannot describe to your Lordship the utter destruction of the works & the town from the fire of our ships.’[27] A midshipman from one of the smaller steamers spoke of hands, arms and toes sticking out of the rubble.[28]

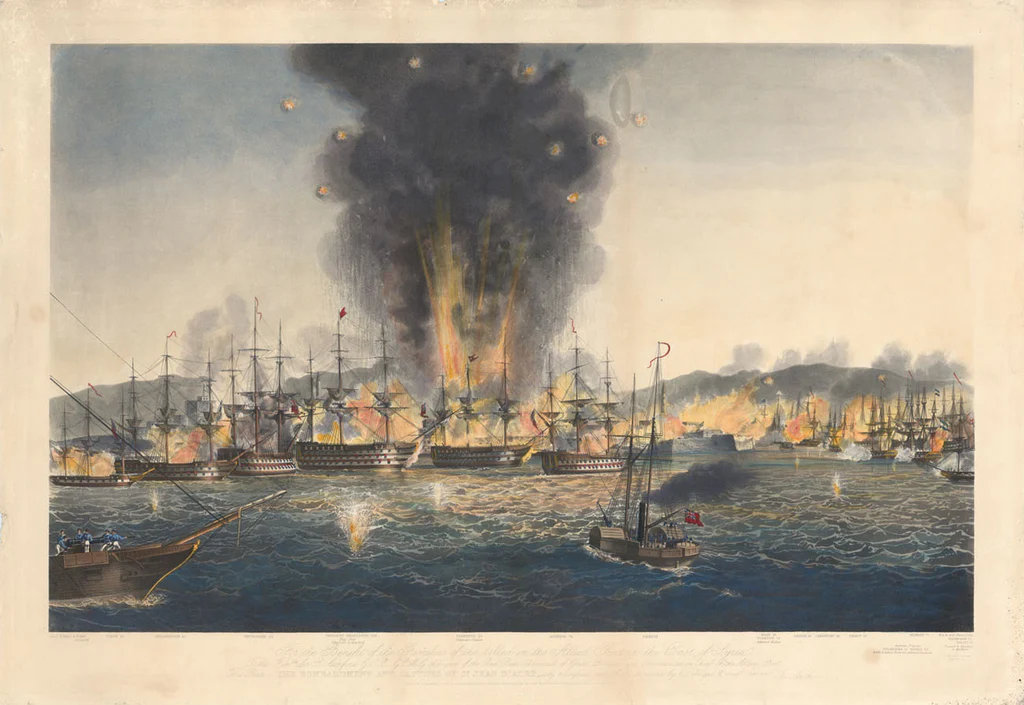

Barely remembered today, this event attracted an enormous amount of fascination in early Victorian Britain. The fortress that held out for half a year against Napoleon went down in less than three days under the blows of the steamships – on the more popular count, less than three hours of concentrated bombing on 3 November. It was a sublime, awe-inspiring, miraculous manifestation of the power of Britain in general and steam in particular, rendered in a series of paintings – here is another one, where a steamboat, possibly the Gorgon, is pointing straight into Akka, its column of smoke communicating with the tremendous eruption from the magazine behind the walls and the minarets: coal on fire, town on fire.

‘Bombardment of St. Jean d’Acre.’ H. Winkles, 1840.

In this lithograph, purporting to describe the scene from the perspective of the Arab defenders, the smoke from a steamboat likewise rises in the centre, while to the left the whole town is blown sky-high:

The explosion was the centrepiece of the action, but it went further. The steamers made use of their ability to maneuvre freely in the waters near the walls of Akka, standing as close as 40 metres away when firing their projectiles, and then driving back out when needed. The bombardment could be more precise, and more devastating, and it went on for almost three days before the explosion. Did the British use this overwhelming power to target Ibrahim Pasha’s forces with the utmost precision? In the most detailed recent reconstruction of the attack, four Israeli researchers write: ‘The bombardment was rather aimed at the town itself. (…) In fact, the object of the bombardment was to compel the garrison to surrender, not by the injury which it might have sustained, but by the killing and misery which it inflicted upon non-combatants.’[29] We might recognise this kind of strategic thinking. Yet another admiral described how it worked: ‘Every shot that cleared the walls smashed the tops of houses, hurling walls and stones down on the heads of people below (…) there was no refuge anywhere.’[30]

Whatever compunctions the disembarking men may or may not have felt, back home in Whitehall, the happiness knew no bounds. Lord Palmerston congratulated the Royal Navy for capturing Akka and securing ‘the operation of the commercial treaties’.[31] The road to free trade in the Middle East had been cleared. This was the great achievement of the steamers, widely praised for their efficiency: they ‘continually shifted their positions during the action, and threw in shot and shells, whenever they saw the most effectual points for doing execution’, observed one report, noticing that ‘it is rather remarkable that not one of the four Steam ships had a single man either killed or wounded.’[32] If the men went through the action without a scratch, however, another resource was nearly exhausted: fuel. After the battle, not one of the four steamers had more than one day’s supply onboard. Practically all the stored coal had been burnt in the pulverisation of Akka.

The fall of the town determined the outcome of the war in one stroke. Ibrahim Pasha’s forces collapsed and beat a disorderly retreat through the coastal plains of Palestine. The steamers continued to harass them, landing at Jaffa and hovering off Gaza. On land, infantry troops moved into Gaza in January 1841, to ensure ‘the destruction of the enemy’s provisions’ – the first time British-led forces occupied this corner of Palestine, if only for a brief moment.[33] The Royal Engineers swiftly produced a map of Gaza, more precisely Gaza City; this is what it looked like in 1841. You can see Shuja’iyya to the right. There is not much of this urban fabric left today.

Royal Engineers: map of Gaza, 1841 (published 1843).

While the British held Gaza and mapped it and destroyed the stores of food – presumably only to deny the Egyptian army its provisions – scattered columns of demoralised, thirsty, hungry soldiers drifted through the desert back into Egypt: less than one fourth of the army Ibrahim had commanded at the outbreak of the war. Before their arrival, Napier steamed onwards to the port of Alexandria, where he threatened to subject that town to the same treatment as Akka, unless Muhammed Ali accepted all British demands. Ali asked to at least keep the province of Palestine; but again, Napier warned that he would ‘lay Alexandria in ashes’.[34] That took Palestine off the table. By the same means, Napier pressed for an immediate implementation of the Balta Liman treaty in Egypt. Ali caved in on this point too.

Thus did Britain destroy the Arab proto-empire by means of steam. From Beirut to Alexandria, it was the steamers of the Royal Navy that formed the vanguard of the victory, more expert than their wind-powered partners in every manoeuvre that profited from mobility in space. In an article on the ‘Iron War Steamers’, the Manchester Guardian quoted an anonymous letter from a British subject in Alexandria:

So much has been done, of late, in the Levant by steam, that everybody is now alive to its capabilities as an element either of war or peace, and is ready to ask ‘What will it do next?’ Ibrahim Pasha can only account for his loss of the coast of Syria in a week by confessing that ‘the steam boats conveyed the enemy here, there, and everywhere, so suddenly that it would have required wings to keep up with them! One might as well think of fighting with a genii!’[35]

This power derived from fossil fuels: steam allowed the admirals and captains to plug their boats into a current from the past, a source of energy external to the space and time of the actual battle, through which the ships could therefore shoot as though they had wings of their own. Britain’s military superiority was radically enhanced by its ability to mobilise the stock as a force for running the enemy down. Or, as the Observer noticed, with reference to Palestine: ‘Steam, even now, almost realizes the idea of military omnipotence and military omnipresence; it is everywhere, and there is no withstanding it.’[36] Britain was ready to project the power of fossil fuels across the globe, after having proved its mettle in Palestine.

*

The country whose fate was most immediately sealed by these events was Egypt. Muhammed Ali’s cotton industry crumbled virtually overnight. When free trade was extended to his shrinking realm, the factories on the Nile could not hold out against the British exports, and the reason for this is fairly straightforward: Egypt had no modern prime movers. It didn’t have water-power, because the Nile is a slowly meandering river with an almost imperceptible gradient, devoid of rapids and falls. Nor did it have steam-power. Instead, Egyptian manufacturing ran overwhelmingly on animate power – oxen or mules or even human muscles impelling machines. But these were sorely deficient sources of energy, compared to steam-engines. They were weak, uneven, disorderly. Why, then, did not Muhammed Ali adopt steam? He wanted nothing more. Closely attuned to the trends of capitalist industry, he developed, from the 1820s onwards, a preoccupation with steam and coal bordering on fixation. He knew that he could stand up to Britain only by copying it, in foundries and factories and on the seas, in economic competition and warfare alike. ‘The English have made many great discoveries, but the best of their discoveries is that of steam navigation’, he would tell Lord Palmerston’s emissary.[37]

But steam demanded its fuel. Ali did not possess any reserves of it. He was acutely aware of this problem, so much so that he sent expeditions into Upper Egypt and Sudan and beyond to try to locate seams of coal. My PhD student Amr Ahmed recently defended his dissertation Egypt Ignited: How Steam Power Arrived on the Nile and Integrated Egypt into Industrial Capitalism (1820s–76). There, he shows how the quest for coal drove the imperial expansion of Muhammed Ali. One of his motives for conquering Syria was the reports of coal in Mount Lebanon. And indeed, coal could be dug out of the hills from under the Druze and the Maronites: in 1837, the Egyptians managed to extract a volume equal to 2.5 per cent of total British output. Apparently, this Lebanese coal was of inferior quality, expensive, evidently not enough to power a shift to steam in the factories of Cairo before the British struck them down. The nascent coal industry in Mount Lebanon also generated trouble for Ali. People were forced into the mines and abhorred the labour, to the extent that they rose up against Ibrahim Pasha’s forces in 1840; and this uprising was exploited by the British for their own political purposes. The revolt against the coal dreams of Ali contributed to his downfall. His project was to create a fossil empire in the lands of the Arabs; like all builders of empire, he was a ruthless tyrant (in 1834, the people of Nablus revolted against him). In the end, the project came to grief, largely because Ali failed to establish proper coal reserves as a foundation of empire. One can only speculate about what would have happened had the Turkish coal supplies, which we know today as very extensive, fallen into his hands. Shortly after the war in 1840, a declining Muhammed Ali exclaimed to a British visitor: ‘coal! coal! coal! That is the one thing needful for me’.[38]

In the 1830s, Egypt balanced on the edge between core and periphery. It embarked on a precocious industrialisation, for a moment the leading ‘emerging economy’, as it would be called today, outside Europe and the US. But this was a moment in time in which access to steam-power and the coal that fuelled it determined the fortunes of nation: without this ticket, and with a rough kick from above, Egypt fell down the stairs. The cotton factories on the Nile soon lay in ruins too. Egypt became an important market for British exports, and an even more important source of supply of raw cotton: a country locked into the position of a periphery. After 1840, it underwent the most extreme deindustrialisation experienced anywhere in the nineteenth century. Around 1900, somewhere between 93 and 100 per cent of its exports consisted of one single crop – an unusual degree of specialisation. By dint of Egypt’s position in the larger Arab world, this underdevelopment also placed the region as a whole in subordination to the advanced capitalist countries of the West: solidified only through the events of 1840, a power relation with very durable results. In Egypt Ignited, Amr continues this story in amazing granular detail and demonstrates how Egypt became subsumed under the fossil economy that revolved around Britain – its economy was eventually permeated by coal and steam, but it was coal and steam imported from Britain, used for the production and transportation of raw materials. I hope his book will soon be published so you can read the full account.

*

The second country whose fate was written in the stars at this time was Palestine. In 1840, the British Empire first proposed the colonisation of that country by Jews. More precisely, on 25 November, Palmerston wrote to Ponsonby, the ambassador in Istanbul: ‘This is a great triumph to us all’ – the fall of Akka, a few weeks old – ‘especially to you, who always maintained that Mehemet’s power would crumble under a European attack.’ And then he went on:

Pray try to do what you can about these Jews; you have no idea to what extent the interest felt about them goes; it would be extremely politic [if we could make] the Sultan give them every encouragement and facility for returning and buying lands in Palestine; and if they were allowed to make use of our consuls & ambassador as the channel of complaint, that is to say, place themselves virtually under our protection, they would come back in considerable numbers, and bring with them much wealth.[39]

57 years before the first Zionist congress, 77 years before the Balfour declaration, 107 years before the partition plan, the chief architect of the British Empire near the summits of its power here laid down the formula for the colonisation of Palestine. For some reason, this particular document appears to have never been cited in the entire historiography. But it’s all there, encapsulated in a missive sent in the euphoria after the pulverisation of Akka.

1840 saw the first mania for what we now know as the Zionist project. It had been in the making for a few years. As is fairly well-known, Britain in the late 1830s saw a surge of Christian Zionism, the doctrine that Jews must be gathered and ‘restored’ to Palestine, where they will convert to Christianity and precipitate the second coming of Christ and usher in the Last Days. The main evangelist of this gospel was the Earl of Shaftesbury, who was related through marriage to Lord Palmerston; he tried to make the most of this family bond, but when he spoke to the foreign secretary, he had to put his religious arguments to the side. Instead he peppered him with reports about ‘the productive powers of the Holy Land’ being ‘for centuries altogether neglected’. If only Britain resolved to insert the Jews into it, Palestine could be turned into a supplier of raw cotton and a market for manufactured goods and ‘our capitalists might be tempted to invest large sums in machinery & cultivation.’[40] After a dinner with Palmerston on 1 August 1840, the godly but shrewd Shaftesbury noted in his diary that ‘I am forced to argue politically, financially, commercially; these considerations strike him home’.[41] But eschatology and empire were not incompatible. Shaftesbury succeeded in getting Britain to open a consulate in Jerusalem in 1838; not by coincidence, this was the same year as Britain pushed into the region through the signing of the Balta Liman treaty. God and Mammon mixed rather well. Lady Palmerston, the wife of the foreign secretary, together with whom he apparently formed his opinions, read the fall of Akka through her Bible:

It cannot be an accident that all these things should have so turned out! My impression is that it is the restoration of the Jews and fulfilment of the Prophecies. (…) It is certainly very curious and Acre seems to have fallen down like the walls of Jericho, and Ibrahim’s army dispersed like the countless hosts that were enemies of the Jews, as we see in the Old Testament.[42]

It should be pointed out already here that this was a wholly gentile, Christian, white Anglo-Saxon fantasy, in which actual Jews living in the Middle East or elsewhere played no active role.

Lord Palmerston himself clearly saw the pulverisation of Akka as a sign of not the end times, but a new era of prosperity. No longer would the cotton industry be cramped by a lack of markets. After what he called ‘the prostration of Mehemet Ali’, Palmerston restated his general philosophy:

We must unremittingly endeavour to find in other parts of the world new wants for the produce from our industry. The world is large enough, and the wants of the human race ample enough to afford a demand for all we can manufacture; but it is the business of the government to open and to secure the roads for the merchant.[43]

It was in this scheme the Jews had a role to play. In another letter – and this document has been cited relatively often – Palmerston told Ponsonby to convince the sultan ‘to encourage the Jews to return and settle in Palestine because the wealth which they would bring with them would increase the resources of the Sultan’s dominions’; moreover, a Jewish settlement would serve ‘as a check upon any future evil designs by Mehemet Ali or his successor.’[44] Throughout the ‘Eastern crisis’, Palmerston again and again dictated the rationale in letters to his ambassador: a ‘return’ of the Jews to Palestine would implant ‘a great number of wealthy capitalists’; if the Sultan would accept them, he would earn the friendship of ‘powerful classes in this country’ (in the UK, that is); ‘the capital and the industry of the Jews would much increase his revenue and add greatly to the strength of his empire.’[45] We can here see a kind of brain scan of imperialist Zionism. Because the Jews would be tied to the metropole, giving Palestine to them would help unfetter capitalist development and prevent the rise of new recalcitrant challengers in the region.

As a measure of just how mainstream this scheme had become, the Times ran an article on 17 August, while Charles Napier was running up and down the Lebanese coast on the Gorgon, explaining that a Jewish settlement of Palestine would function as ‘a breastwork against the further encroachments of lawless tyranny and of social degeneracy’ – in short, it would be ‘advantageously employed for the interests of civilization in the East.’[46] On the ground, the advance detachments of Zionism were formed by officers in the imperial bureaucracy. Some of them came fresh from the battlefield. A colonel by the name of Churchill – Charles Henry, distant relative of the more famous Winston – commanded the British forces that marched into Damascus in early 1841, assembled various dignitaries in a hall and gave a speech:

Yes, my friends! there was once a Jewish people! famous in arts and renowned in war. These beautiful plains and valleys, which are now tenanted by the wild and wandering Arab, on which desolation has fixed her iron stamp, once revelled in the luxuriance of their fertile and abundant crops, and resounded with the songs of the daughters of Zion. May the hour of Israel’s deliverance be near at hand![47]

This Churchill was well aware that there was no, as he put it, ‘strong notion among Europe’s Jews to return to Palestine.’[48] The desire of Jews to stay where they lived frustrated him. Equally frustrating, his government stuck to the policy of keeping the Ottoman Empire intact, under British guardianship and custody. He wished to see it broken up, and Jewish colonisation of Palestine would be just the right hammer. In a long letter to Moses Montefiore, president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, sent from Damascus, where he was installed as consul, Churchill exhorted him to convince his fellow Jews to go to Palestine, and perhaps Syria too:

you would end by obtaining the sovereignty of at least Palestine. (…) I am perfectly certain that these countries must be rescued from the grasp of ignorant and fanatical rulers, that the march of civilisation must progress, and its various elements of commercial prosperity must be developed. It is needless to observe that such will never be the case under the blundering and decrepit despotism of the Turks or the Egyptians. Syria and Palestine, in a word, must be taken under European protection and governed in the sense and according to the spirit of European administration. It must ultimately come to this.

Churchill envisioned a Jewish entity in Palestine under the protection of Britain and its allies, armed for ‘defence against the incursions of Bedouin Arabs’.[49]

Another man who hurried into Palestine at this auspicious moment was George Gawler. Having just relocated from South Australia, where he had been governor, he penned a pamphlet called ‘Tranquilization of Syria and the East: Practical Suggestions in Furtherance of the Establishment of Jewish Colonies in Palestine, the Most Sober and Sensible Remedy for the Miseries of Asiatic Turkey’. He travelled in Palestine in the early 1840s and somehow managed to perceive it as ‘a fertile country, nine tenths of which lie desolate.’ The land was empty, save for a few ‘unlettered and restless Bedawy’ now and then encountered in ‘deserted cities, and thorn-covered plains’. Solution: ‘REPLENISH THE DESERTED TOWNS AND FIELDS OF PALESTINE WITH THE ENERGETIC PEOPLE’, the Jews, who would turn it into a flourishing marketplace under the watch of a ‘naval force frequently on the coast’ – the British steamers, that is.[50] A friend of Palmerston, E. L. Mitford, likewise imagined Palestine as ‘barren and desolate’. Jewish colonisation would bring ‘blessings on England and be felt in the wretched hearts and homes of the poor manufacturers of Manchester, Birmingham and Glasgow’; of particular importance, it would facilitate fossil-fuelled entrenchment in the region and beyond.[51] An independent Jewish state under British protection would ‘place the management of our steam communication entirely in our hands and would place us in a commanding position in the Levant from whence to check the process of encroachment, to overawe open enemies and, if necessary, to repel their advance.’[52] Such was the formula printed out by the events of 1840.

This, then, was the moment of conception for two interrelated principles: one, no people exist in Palestine; two, the land must be taken with the force of technology running on fossil fuels. As for the former, contemporary Zionists debate who first came up with the slogan ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’, but there is consensus that it happened around the year 1840. Some point to an article Shaftesbury wrote in the Times in 1839, where he used the phrase ‘Earth without people – people without land’, Earth without people sounding perhaps slightly more chilling today. Others give the honour to his fellow Christian Zionist Alexander Keith, who went on an expedition to Palestine in 1839 and somehow managed to return with the impression that this was a ‘country without a people’ crying out for the arrival of ‘a people without a country’. The cities and towns of Palestine were ‘desolate without an inhabitant’; from Gaza to al-Khalil, all Keith could observe were ‘deserted sites and ruined villages, not one of them being inhabited.’[53] But now a miracle had transpired. ‘As if commissioned by the Lord’, Keith wrote of Akka, ‘a bomb penetrated a magazine of powder stored up for defence, and raised the arsenal in the air, as if to show that the time was come that the last fortress in Palestine should cease, and strewed it stone by stone upon the ground’ – strewed it stone by stone upon the ground – ‘as if the times too were not distant when the hands of strangers should find other work, and build up the ruined walls in another form. (…) Acre fell to the lot of a tribe of Israel.’[54]

It now became a persistent theme of British commentary on Palestine that no people lived in that land. Shaftesbury informed Palmerston that Jewish colonisation would be ‘the cheapest and safest mode of supplying the wastes of those depopulated regions.’[55] The Morning Post published a typical article claiming that ‘Syria and Palestine are depopulated’, voids in which the ‘sons’ of ‘the Arabian wilderness’ had failed to ‘establish themselves and maintain their nationality.’ The year 1840 was here calculated to match a Biblical prophecy of Jewish restoration.[56] Such fusion of eschatology and empire became very much in vogue after Akka, as in perhaps the most peculiar tract to emerge from this moment, an anonymously authored 350-pages mishmash of exegesis and realpolitik and steam fetishism called ‘The Kings of the East’. Here too, Palestine was said to have ‘few’ inhabitants, and the fall of Akka was hailed as a divine intervention by means of steam, the pillar of British power.[57] As proof of the metaphysical significance of Akka, the author quoted a first-hand report of how ‘the town is a complete mass of ruins: not a house in the place, however small, has escaped the fury of our shot. (…) Everything bears the most ample witness of the matchless precision of our guns’ – praise the Lord: ‘thousands of her garrison numbered with the dying and the dead.’[58] Ergo, restoration was imminent. This author alleged that ‘the Jews are commencing to return to Judea’.[59]

Two verses of the Bible shed special light on this process. At the opening of the 18th chapter of Isaiah, in the King James version, we read: ‘Woe to the land shadowing with wings, which is beyond the rivers of Ethiopia:That sendeth ambassadors by the sea, even in vessels of bulrushes upon the waters, saying, Go, ye swift messengers, to a nation scattered and peeled’ – what kind of vessels did the prophet talk about here? Patently, he must have had British steamboats in mind.[60] They were the ones sending ambassadors by the sea to open Palestine for the Jews. From this, the author inferred a novel prophecy: Britain ‘WILL ISSUE A PROCLAMATION, guaranteeing to all Jews who will return to Syria their protection’.[61]

The mania also crossed the Atlantic and reached the United States of America. In the weeks before the fall of Akka, one influential, relatively progressive periodical, The Western Messenger, knew which way the wind was blowing. ‘Now that steam ships ride in the bay of Alexandria, and steamboats break the waters of the Nile, and the roar of steam cars, dashing over railways, is heard, is it not morally certain that the Moslem power has ceased?’ The time had come to ‘give the Jews possession of Palestine.’[62] They would take and defend the land with military might and send all sorts of profit flowing back to the West. But the first American Zionist of import, who, unlike nearly all of his British counterparts, also happened to be Jewish, was Mordecai Manuel Noah.[63] In 1844, he delivered a Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews. He never visited Palestine, but he seems to have learned from British travellers that ‘the land is now desolate’ – although he did relay that ‘olives and olive oil are everywhere found’, and wheat and corn and cotton and tobacco grow in the plains and hills, and ‘grapes of the largest kind flourish everywhere’. Now ‘great and important revolutions’ were underway in that land. Noah latched onto the view that the demise of Ali heralded ‘the organization of a powerful government in Judea’: and he implored the US to take it under its wings.[64]

Noah likewise read Isaiah 18. He deepened the exegesis one notch by reading it directly in Hebrew and finding that the prophet called the vessels gomey. This Hebrew word could also mean ‘an impetus, a forcible propelling power’ – further evidence that the prophet referred to steam. But in Noah’s reading, the steam-power would be American, not British. ‘The land lying beyond the rivers of Ethiopia is America’ and the vessels ‘our steam vessels’, with a divine mission to settle the Jews in Palestine.[65] ‘The discovery and application of steam will be found to be a great auxiliary in the promotion of this interesting experiment.’ It placed American Jews ‘within a few days’ travel of Jerusalem. Our Mediterranean and Levant trade, hitherto much neglected, will be revived, affording facilities to reach Palestine from this country direct.’[66] Reverting to the default view that no economic activities were occurring as of now, Noah anticipated that ‘the ports of the Mediterranean will be again opened to the busy hum of commerce; the fields will again bear the fruitful harvest’.[67] He looked forward to a future when

the whole territory surrounding Jerusalem, including the villages Hebron, Safat, Tyre, also Beyroot, Jaffa, and other ports of the Mediterranean, will be occupied by enterprising Jews. The valleys of the Jordan will be filled by agriculturists from the north of Germany, Poland, and Russia. Merchants will occupy the seaports, and the commanding positions within the walls of Jerusalem will be purchased by the wealthy and pious of our brethren.[68]

Some prophecies do come true.

*

What do we make of all this? Here is the first moment of articulation: the moment that ignited the globalisation of steam, through its deployment in war, was also the moment that conceived the Zionist project. But there was no perfect synchrony. Zionism was as yet only an idea. No Jewish settlement in Palestine developed in the wake of 1840; strictly speaking, the Palmerstons, Shaftesbury, Churchill, Gawler, Noah and the others all failed. They were ahead of their time, by half a century. But when the Zionist movement was eventually assembled, it was a wagon that could be placed on ready-made tracks, laid out by the British Empire after 1840: the dominant classes of the metropole had already constructed the logic of its satellite colony in Palestine, if only as a mental image. Zionism did not take material form in 1840, like the exercise of steam-powered violence did. We might conclude from this that the latter had causal primacy in history. Zionism first existed at the level of superstructure, on the base of the fossil empire.

I do not say this with a pretension to revolutionary discovery. The broad contours of this story can be found in the existing historiography, including the most recent sustained engagement with the period, Promised Lands: The British and the Ottoman Middle East by Jonathan Parry. He chronicles how the British thrust into the region by means of steam. ‘From the 1830s, steam power’, he writes, ‘was a valuable aid in intimidating Arabs into appreciating British might.’[69] Beyond the Levant, two Arab lands in particular were subjected to this might: Yemen and Iraq. In 1839, Aden was occupied and annexed as a coaling station for steamboats; in the late 1830s, various experiments with steam communication were launched on the Euphrates. By 1841, when the British had done away with the main obstacle, ‘their regional naval supremacy was undisputed. Whether steam might civilise the Arabs was a question for the long term’, Parry coyly adds.[70] He works in the tradition of gentlemanly, tea-sipping British history-writing and so refuses to draw out implications or follow lines; he also studiously ignores political economy and represses the mountains of evidence for how the dynamics of capital accumulation propelled the expansion into the Middle East – evidence of which I have only here provided the tiniest sample. But the attentive reader can make out the narrative arc.

‘A large proportion of the things the British ever thought about the Middle East had already been thought by 1854’, states Parry.[71] We can sharpen this and state that a large proportion of the things the British and the Americans ever thought about Palestine had already been thought by 1844. And it began with extreme technological superiority, the penetration of the region by means of cutting-edge fossil-fuelled machines. That kind of subjugation would remain in place up to the present day; what happened in 1840 was no ephemeral intrusion, like Napoleon’s campaigns. The British would not let go of the Middle East – they moved only deeper and deeper into it, until in the last decade of the nineteenth century, having occupied Egypt, they had risen so high as to lay the Ottoman Empire low enough for colonisation of Palestine to get going. All the UK ever did was to share this power with and pass it on to the US. But as the ongoing bombardment of Yemen testifies, the British are still very much there.

A few more words on the dialectic of mind and matter may be in order. There is an odd spiral of reality and fantasy at work in the moment of 1840: the British really did turn one Palestinian town into ruins. Then they started imagining that all of Palestine was one landscape of ruins – desolate, deserted, depopulated; fanciful constructions at best, but rather adequate representations of what Akka seems to have looked like after 3 November. In the next coils of the spiral, the ideational emptying of the land became a precursor to the real thing. ‘Earth without people’ read the prescription for a Nakba. Ever the pioneers, the British undertook a prefigurative elimination of the Palestinian people. At this moment in time, curiously, Jews still had a position rather symmetrical to the Palestinians: they existed as characters in the plot, but purely in the realm of the imagination. Actual Jews did not count. Jews did not clamour to abandon their homes for Palestine – rather, to the contrary, as even one Zionist scholar has noticed, ‘British Jewry was opposed to “anything that might seem to impugn its status as ‘wholly’ English.” English Jews could only be embarrassed by the suggestion that they were waiting to go back to Palestine’.[72] Before Zionism was Jewish, it was imperial.

But real Jews would, of course, in time be recruited into the Zionist project, and real Palestinians would be erased from physical existence in their land. Set in the context of this longue durée, the genocide in Gaza does not appear all that accidental. In her report to the UN, Albanese is brave enough to draw on the school of settler-colonial studies to explain it. She writes: ‘Israel’s actions have been driven by a genocidal logic integral to its settler-colonial project in Palestine, signalling a tragedy foretold.’ Genocidal extermination is the climax of settler colonialism, and in Palestine, from the moment of 1948, ‘displacing and erasing the Indigenous Arab presence has been an inevitable part of the forming of Israel as a “Jewish state”.’ [73] She is right, of course. But settler colonialism in Palestine never stood on its own feet and never could have. And the tragedy was foretold earlier than by Yosef Weitz and his likes. The Palestinians were figuratively spirited out of Palestine already 183 years before this genocide; with some interruptions and fits and starts, the materialisation and escalation of the act have been in motion ever since. Consider the words from Isaac Herzog, president of the occupation, adduced by Albanese as one instance of genocidal intent: he affirmed in October and November that his entity fights on behalf of ‘all civilized states… and peoples’, against ‘a barbarism that has no place in the modern world’ – it will ‘uproot evil and it will be good for the entire region and the world.’[74] These words could have been put in his mouth by the Anglo-Zionists of 1840.

We might paraphrase the motto of the school of settler-colonial studies and say that imperial support for the Zionist entity is a structure, not an event. The structure was forged by the exceptional power accorded to those armed with fossil fuels and has continued to function that way, as I will now briefly argue, but before I do so, let me point out one last thing about 1840: the account I have given here is sketchy and partial. Most problematically, it relies exclusively on English sources. I do not read Arabic, so I cannot say whether there is an Arabic historiography of 1840. Nor does Parry read Arabic, but he tells us: ‘There are many non-English archives that seem not yet to have been fully used by anyone.’[75] Whatever Arabic sources from and about 1840 exist, and whatever they say about this original encounter with the power of steam and the notions of Zionism, they have not yet left a trace in the English literature. Deep research on this moment would begin with some digging outside the metropole.

*

Now I will be extremely sweeping and synoptic in what follows. When the first Zionist colonies were built, one could find excited reports in the Western press: ‘The Jews who are now going to Palestine take with them the progressive spirit of the century, and before long travellers in that country may hear the steam whistle, and the clatter of machinery, and see all around them the bustle of business instead of the traditional apathy and listlessness of the Orient’, the National Repository rejoiced in 1877.[76] When the British Empire occupied Palestine and set about implementing the Balfour declaration, the fossil fuel of the day was not coal. It was oil. Promising deposits had been located in the countries bordering the Persian Gulf, and the central industrial project of the Mandate came to be the pipeline that brought crude oil all the way from Iraq, across the northern West Bank and the Galilee, to the refinery of Haifa. The Mandate as such cannot be understood outside the deepening control over the region in the pursuit of oil; and the Mandate used oil to reallocate land from Palestinians to Jews. In his forthcoming Heat: A History, a wonderfully rich history of high temperatures and fossil fuels in the Middle East, On Barak shows, among many other things, how the Yishuv wrested citrus production from Palestinians by linking up with the most modern circuits of technology: irrigating their orchards with fossil-fuelled pumps, loading their fruits on lorries, sending them over roads to ports, offloading them onto steamers to the European market – a symbiosis with the fossil empire by which the natives could be squeezed out of their iconic citriculture. The Mandate authorities systematically privileged the building of roads between colonies. Oil-based infrastructure tilted Palestine in the direction of the settlements on the coastal plains and further towards their patrons on the other side of the ocean.

When Zionist forces began to terrorise the Palestinians of Haifa to drive them out of the city, Ilan Pappe tells us, ‘rivers of ignited oil and fuel [were] sent down the mountainside’.[77] When the top echelons of the US empire discussed whether to throw in their lot with the Zionists during the Nakba, they had oil interests foremost in mind. Some argued that these would be better served by siding with the Arabs. But as Irene L. Gendzier has demonstrated in Dying to Forget: Oil, Power, Palestine and the Foundations of U. S. Policy in the Middle East, the government was swayed by the argument that a Palestinian victory would ‘increase Arab self-reliance, demands and bargaining power’, whereas the establishment of the state of Israel ‘would have a soothing effect on the Arabs and make them regain their right sense of proportion’; moreover, ‘the Yishuv is a Western progressive factor, which will be a great stimulant to any social progress in the Middle East, which will open new commercial markets’.[78] The American oil companies seem to have converged on the view that control over deposits would be indirectly reinforced by having Israel as an ally in the region. And that is indeed what transpired during the 1950s and 60s, the golden age of the seven sisters and Gulf oil. When the US took over the role as the number one backer of Israel after 1967, the defence of this status quo was the paramount concern: in The Global Offensive: The United States, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the Making of the Post-Cold War Order, Paul Thomas Chamberlin describes how the US regarded Palestinian liberation as a threat to the domination of the Middle East as a whole, with all its invaluable oil reserves. Conversely, ‘Israel was fast proving its value as a key strategic asset in the Middle East and a model regional policeman in the Third World.’[79] Proof of this logic came from the event known as Black September, one of the eternal recurrences, depicted in a letter from Yassir Arafat on 22 September 1970: ‘Amman is burning for the sixth day. (…) The bodies of thousands of our people are rotting beneath the rubble.’[80]

All of this, it should now be clear, followed the script first laid down in 1840. If Plan Dalet was a settler-colonial script for the destruction of Palestine from 1948 onwards, it was preceded by – and had its conditions of existence in – the imperialist vision of an entity imposed on the land of Palestine for the protection of the interests of the core: access to raw materials and markets, prevention of subversive projects, buffer zones and counterweights against more distant rivals. In 1840, it was cotton, Muhammed Ali and Tsarist Russia. 127 years later, when the occupation was completed, it was petroleum, third world liberation and the Soviet Union. We are dealing here with an exceedingly deep structure, not an event or two; a ratcheting up and escalation across two centuries, a worsening and intensification of patterns first developed in the early nineteenth – also, not coincidentally, the temporal form of global warming itself. I have pointed very quickly and superficially to three further pivotal moments of articulation. In 1917 and after, the British occupation of Palestine was part of the transformation of the Middle East into a foundation for fossil capital, by dint of its oil resources. In 1947 and after, Western support for the new Zionist state was informed by the consummation of that order; in 1967 and after, by its defence. The steps along the way to the destruction of Palestine were simultaneously steps along the way to that of the Earth.

*

If we now jump to the present situation, we should first consider the role of the state of Israel in the ongoing fossil fuel frenzy. In Overshoot, Wim and I show in some detail how the 2020s have so far seen an accelerated expansion of fossil fuel production, just when it had to be reined in and inverted into its opposite – a sustained dismantling – for the world to avoid a warming of more than 1.5 or 2 degrees. This expansion doesn’t stop, it goes on and it goes on and it doesn’t stop and then it continues and proceeds apace: as the Guardian reported just the other day, corporations and states are forging ahead with new oil and gas projects in ever-growing volumes. The country leading the expansion is, of course, the US; second on the list is Guyana, but that is only because ExxonMobil has found its most recent treasure trove in its waters. And for the first time, the Zionist entity is now directly involved. One of the many frontiers of oil and gas extraction is the Levant basin along the coast running from Beirut via Akka to Gaza. Two of the major gas fields discovered here, called Karish and Leviathan, are in waters claimed by Lebanon. What does the West think of this dispute? In 2015, Germany sold four warships to Israel so it could better defend its gas platforms against any eventualities. Seven years later, in 2022, as the war in Ukraine caused a crisis on the gas market, the state of Israel was for the first time elevated into a fossil fuel exporter of note, supplying Germany and other EU states with gas as well as crude oil from Leviathan and Karish, which came online in October of that year. 2022 sealed the high status of Israel in this department.

A year later, Toufan al-Aqsa threw a spanner in the expansion. It posed a direct threat to the Tamar gas platform, which can be seen from northern Gaza on a clear day; in the range of rocket fire, the platform was shut down. A major player on the Tamar field is Chevron. On 9 October, the New York Times reported: ‘The fierce fighting could slow the pace of energy investment in the region, just as the eastern Mediterranean’s prospects as an energy center have gained momentum. Israel used to be one of the few countries in the Middle East without significant discovered petroleum resources. Now, natural gas has become a mainstay of its economy’, but the Palestinian resistance could upend this equation. Five weeks after 7 October, however, when most of northern Gaza had been comfortably turned into rubble, Chevron resumed operations at the Tamar gas field. In February, it announced another round of investment to further bolster output. In late October, the day after the ground invasion of Gaza began, the state of Israel awarded 12 licenses for the exploration of new gas fields – one of the companies picking them up being BP, the very same company that first discovered oil in the Middle East and built the Kirkuk-Haifa pipeline.

But the imbrications now go both ways. Israeli capital has in recent years become a major player in the expansion of oil and gas production in the North Sea. One of the companies based in Tel Aviv and spearheading extraction off Akka as well as the Shetland Islands is Ithaca Energy: it now owns one of the most destructive carbon bombs planted in the British sector of the North Sea, the Cambo field, and one fifth of another, the Rosebank field, and it hungrily explores for more. When Ithaca entered the London stock exchange in 2022, it was the largest floatation of that year. BP is looking for gas in the waters of Palestine; Ithaca is looking for it in the waters of Britain: the harmony has never been greater. The genocide is unfolding at a time when the state of Israel is more deeply integrated in the primitive accumulation of fossil capital than it has ever been. The Palestinians, on the other hand, have zero stake in that process: no platforms, no rigs, no pipelines, no companies listed on the London Stock Exchange. But Arabs in the UAE and Egypt and Saudi Arabia do, of course. This is the political economy of the Abraham Accords and its expected sequels: a unification of Israeli and Gulf capital in the process of making money by producing oil and gas. This is the political ecology of normalisation: a sacralisation of the business-as-usual that destroys first Palestine and then the Earth.

*

The destruction of Gaza is executed by tanks and fighter jets pouring out their projectiles over the land: the Merkavas and the F-16s sending their hellfire over the Palestinians, the rockets and bombs that turn everything into rubble – but only after the explosive force of fossil fuel combustion has put them on the right trajectory. All these military vehicles run on petroleum. So do the supply flights from the US, the Boeings that ferry the missiles over the permanent airbridge. An early, provisional, conservative analysis found that emissions caused during the first 60 days of the war equalled annual emissions of between 20 and 33 low-emitting countries: a sudden spike, a plume of CO2 rising over the debris of Gaza. If I repeat the point here, it is because the cycle is self-repeating, only growing in scale and size: Western forces pulverise the living quarters of Palestine by mobilising the boundless capacity for destruction only fossil fuels can give.

It is easy to forget just how central military violence has been and remains to business-as-usual. More than 5 per cent of annual CO2 emissions stem from the militaries around the world. We often talk about flying and how bad it is for the climate, and it is bad, but civil aviation accounts for about 3 per cent of the total. And the 5 that come from militaries precede actual war: these are peacetime emissions, made in the process of maintaining the logistical apparatuses and fighting capacities of armies before they go to the war. When they do go to battle, the fuel is set on fire and the bombs rain down in bursts of concentrated additional emissions. The US, of course, is at the centre of all this. The emissions from the occupation army during the war on Gaza might be counted as just another category of American emissions. The US outweighs every other country; indeed, as Neta C. Crawford notes, ‘the US military is the single largest institutional fossil fuel user in the world and thus the world’s single largest greenhouse gas emitter.’[81] In her book The Pentagon, Climate Change, and War, she brilliantly charts the development of what she calls ‘the deep cycle’. The militaries of first the UK and then the US found coal, followed by oil, to be indispensable for waging war: for manufacturing weapons, transporting soldiers into the battlefield, providing mobility once engaged, bringing firepower to bear on the enemy. By basing its operations on fossil fuels, the US military contributed to their spread throughout the economy; and when both military and economy were thoroughly dependent on them, the protection of this essential commodity itself became an imperative of war. No part of the world has been so deeply formed and scarred by this cycle as the Middle East. Although Palestine is at its centre, the devastation clearly extends to other countries too: think only of Iraq and Yemen.

*

Let us then revisit the question of the nature of the alliance and briefly reconsider the theory of the lobby. It says, in short, the following: the Zionist lobby in the US has amassed so much financial and electoral and media power as to hold American politics in an iron grip. Through its machinations and manipulations, it has compelled the US to support Israel, despite this not being in the real, rational, material interests of the country. The US backs Israel for reasons of domestic politics, which distort the preferences and standing of the US on the international arena. The theory is, of course, based on the work of John Mearsheimer, a man of the US military, a so-called realist with no ideological affinity to the left. I find the avid reception of his work on parts of the left rather surprising. Space does not allow for a comprehensive critique of either Mearsheimer or his echoes on the left: here I shall only point out some of the problems, in one representative rendition of the theory.

Married to Another Man: Israel’s Dilemma in Palestine by Ghada Karmi is a fairly widely read and average statement of the case for Palestine in the early twenty-first century. She correctly observes that for Palestinians, understanding the nature of the alliance between the US and Israel is ‘no intellectual game but a matter of life and death.’[82] She poses two alternative explanations: ‘Was US policy so controlled by Israel and its supporters that it was they who primarily dictated it, or was Israel but the imperialist arm of America (and the West) in the Middle East?’, and she comes down firmly on the side of the former.[83] She goes on an unclear rant about Jews in media and Hollywood and concludes that this country is the victim of ‘a foreign state’s penetration into the US system’. A typical counterfactual is constructed: ‘Had the situation been one of rational, pragmatic common sense, where the facts could be examined and the logical conclusions drawn, then the American national interest would ultimately have prevailed over the forces working on Israel’s behalf.’[84]

If only the US state were free to pick the policy that would best serve its interests, it would dump Israel. But the Zionist lobby denies the state that freedom. This distortionist explanation applies not only to Palestine, but to the region in its entirety. Everything the US does in the Middle East is dictated by Israel, against its true interests. ‘The real motivation for the invasion of Iraq’, we learn, was ‘the desire to protect the Jewish state’ foisted onto the US; there were no weapons of mass destruction, no al-Qaida, no terrorism in Iraq, so ‘it must have been Israel’s security that was the motive for attacking Iraq, in the absence of any other.’ This is a double non sequitur. It does not follow from the absence of these official casus belli that the real reason must have been the security of Israel; but it does follow from their absence that the security of Israel was not threatened by Saddam Hussein. Karmi wants us to believe that Israel was out for the Iraqi oil and sent businessmen and advisors and intelligence agents into the country, whereas the US itself possessed none of these aggressive drives, dragged passively into the war by the lobby. We are asked to believe, in other words, that the most powerful empire in the history of the world has no interests and performs no aggressions of its own in the Middle East. It is the same with Syria and Iran, Karmi tells us: what the US does to those countries, it does slavishly on behalf of Israel.