Finally, an Answer to a Mystery Surrounding These 1,000-Year-Old Trees

AFRICA, 1 Jul 2024

Tom Page | CNN - TRANSCEND Media Service

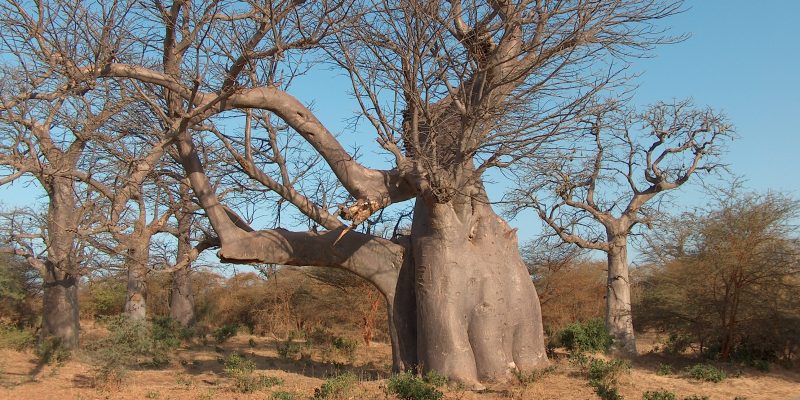

“Avenue of the Baobabs” in Western Madagascar is one of the most spectacular collections of the unusual trees. Gavinevans/Creative Commons

24 Jun 2024 – For millions of years, mighty baobabs have been standing sentry on three different landmasses, posing each other an existential question: Which came first?

The giant trees, swollen of trunk and stubby of canopy, are unmistakable. Baobabs can live for more than 1,000 years, acting as the keystone species in dry forest environments in Madagascar, a swathe of continental Africa, and northwest Australia. Known as “mother of the forest” and “the tree of life,” nearly every part of the tree can be used by humans and animals, meaning they’re of enormous value to each ecosystem they inhabit.

Their reputation has only been burnished by the mystery as to where they originated. Until now, science has had to make do with multiple conflicting hypotheses – the dominant theory being that they came from mainland Africa. Not so, according to a study published last month in the journal Nature. A team of international academics successfully sequenced the genomes of each of the eight baobab species, examining their relationship with one another and concluded that they originated in Madagascar.

The news comes as the trees face a precipitous decline on the island, home to six baobab species, with one likely to become extinct by 2080 according to the study, unless significant interventions are put in place.

Biologists had struggled to determine the tree’s origins, as no fossils of ancient baobabs or their ancestors have been discovered, explained Dr. Wan Jun-Nan, one of the authors of the study, a researcher at the Wuhan Botanical Garden in Hubei, China. What genetic data had been retrieved from baobabs in previous studies was limited, he continued. But with the first full genome sequence of each species, “we can tell a good story about the evolutionary history,” he argued.

That story begins with the rise of baobabs in Madagascar around 21 million years ago, before the genus (scientific name Adansonia) began to diversify, and two species made their way to Africa and Australia around 12 million years ago. This occurred well after the separation of the “supercontinent” Gondwana, so the baobab is likely to have spread through seeds carried across the ocean on floating debris caused by flash floods, according to the researchers.

The study, a collaboration between Wuhan Botanical Gardens, China, the Royal Botanic Gardens in the UK, the University of Antananarivo in Madagascar and Queen Mary University of London, was also able to trace the interspecies gene flow of the eight types of baobab for the first time. This data, which demonstrated low genetic diversity between two species, and inbreeding of one species with another more populous species, offers insights into the competition between baobabs today, said Dr. Wan, and could help protect the trees of tomorrow.

“We hope that in the future, the people of Madagascar can take care of baobabs (by) considering them as different species, not as a whole,” he added.

Only one baobab species is not included in the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species: A. digitata, which populates mainland Africa. Three species in Madagascar are threatened with extinction, and the study recommended the IUCN recategorize one, A. suarezensis, from “endangered” to “critically endangered.” Climate modeling indicated the species could become extinct within 50 years without greater intervention.

That prediction is “plausible” and “highlights the urgent need for action,” according to Dr. Seheno Andriantsaralaza, a tropical ecologist working in Madagascar.

Dr. Andriantsaralaza, who was not involved in the research, supported the call to update the IUCN status of certain Malagasy baobabs. Though she described the study as “fantastic and meaningful,” yielding “valuable” genetic data insights, she cautioned that it represented “just one piece of the puzzle in understanding the evolutionary history and dispersal mechanisms of these iconic giant trees.”

The study’s modeling concluded the range of baobab species has been reducing on the island for millennia, with human-caused climate change and ongoing deforestation exacerbating the shrinkage and fragmentation of baobab populations in recent decades.

Dr. Andriantsaralaza said “it’s crucial to recognize that amidst the challenges, there are local success stories and initiatives led by local organizations and local researchers.”

She cited conservation group Madagasikara Voakajy, which coordinates projects on the north of the island that have focused on protecting A. perrieri and A. suarezensis. Also PEER, a USAID-backed program she is involved in, aims to empower locals to contribute to the sustainable management of the ecosystem.

“Madagascar’s baobab forests belong to the local communities that rely on natural resources to feed their families,” she added. “They should be part of the solution, not the problem.”

Dr. Wan said he hoped the research and media attention would prompt further conservation efforts of the island’s baobabs.

While hailing the breakthrough, he acknowledged the study’s limitations – only one individual per species was sequenced – though hoped future research would expand sampling and answer further outstanding questions about the trees.

The likelihood of finding fossil evidence to rubberstamp the conclusions of the genetic data is slim, Dr. Wan conceded. So perhaps these majestic trees may retain some of their mystery after all.

Tags: Australia, Baobabs, Ecology, Environment, Madagascar, Nature, The Little Prince

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.