Henry Kissinger, Johan Galtung and the Nobel Peace Prize

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 18 Nov 2024

Prof. Syed Sikander Mehdi | Pakistan Horizon – TRANSCEND Media Service

Abstract

20 Aug 2024 – Within a span of three months, two titanic figures passed away. Henry Alfred Kissing, former US Secretary of State and National Security Adviser between 1969 and 1977, died on 29 November 2023 and Johan Vincent Galtung, Father of Peace Studies, on 17 February 2024. Both were global influentials in their own way. Through their teaching, research, publications and discourses on war, conflict, violence, governance, power, security and peace, both influenced the power political world and the world of ideas for more than 60 years. Both significantly, albeit starkly differently, contributed to the evolution of political culture at local, regional and international levels in the post Second World War era. They will be remembered for the position they took on the challenges faced by humanity during the Cold War and after. Both will also be remembered for the unfortunate decision taken by the Oslo-based Norwegian Nobel Committee to award the Peace Prize to Kissinger in 1973 and deny the same to their native son – Galtung.

This paper discusses the life, achievements and works of Kissinger and Galtung and attempts to understand why Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize and Galtung was not. It also discusses the salient features and trends of the award and assesses the impact of the two opposite decisions on the credibility of the Peace Prize itself and on the worldwide movement for peace, justice and change.

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is the most prestigious international prize awarded to one individual or two, or a maximum of three individuals for their services to promote peace in their lifetime. Official announcement of the Prize is made during the first two weeks of October, and the Prize is awarded on 10 December in a formal ceremony in Oslo. On 10 December is also the death anniversary of the founder of all the Nobel Prizes – Alfred Nobel. So far, 141 Nobel Laureates have been awarded this Prize. The Laureates include 111 individuals and 27 organizations. Among the organizations, the Red Cross received the Prize three times (in 1917, 1944 and 1963), and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) two times (in 1954 and 1981).

Even a cursory glance at the list of the Noble Peace Laureates and a sketchy review of the careers and services of the recipients may indicate that the selection process isn’t too rigid and inflexible. It is ever evolving and improvising. For instance, a statement of Nobel Peace Prize Organization informs: ‘Up until 1960, the Nobel Peace Prize was almost exclusively the preserve of highly educated white men from Europe and the USA.

Only once had the prize gone to a candidate from a country outside Europe and the US, when it was awarded to the Argentine Foreign Minister Carlos Saavedra Lamas (1936)’. The gradual globalization of the Peace Prize began in 1960, when Albert John Luthuli, the Zulu chief, teacher and religious leader from South Africa, was awarded the prize. The speed picked up in the 1980s and 1990s, and the trend has been further firmed up from 2001 on. Again, while the first Nobel Peace Prize awarded to a woman, the Austrian novelist and peace activist Bertha von Suttner, within five years of the launch of the Prize (in 1905), only 19 women have been awarded the Prize so far.

In contrast, 92 men have received this award. However, the Norwegian Nobel Committee responsible for the final selection of the candidate or candidates for the Prize seems to be keen to make amends for neglecting the peacemaking and peace building role of women from around the world and causing a huge gender imbalance in the awards given. While only ten women were awarded the prize during hundred years (between 1901 and 2002), nine women received this prize during the next 24 years (from 2003 to 2024).

Similarly, a closer look at the list of the recipients and their background, their clout and role in peacemaking and peace building may indicate the Nobel Committee’s flexible approach towards making the final selection. It may further indicate the shift in the Committee’s concern towards old and emerging global issues from time to time and era to era. A report of the Nobel Peace Prize Organization says:

In the earliest years of the Peace Prize – up to World War I – the prize was often awarded to pioneers of the organized peace movement. In the inter-war years, the focus shifted to active politicians who sought to promote international peace, stability and justice by means of diplomacy and international agreements, but prizes were also awarded for humanitarian work (Nansen, the League of Nations High Commissioner for Refugees).

Since World War II, the Peace Prize has principally been awarded to honour efforts in four main areas: arms control and disarmament, peace negotiation, democracy and human rights, and work aimed at creating a better organized and more peaceful world. In the 21st century the Nobel Committee has embraced efforts to limit the harm done by man-made climate change and threats to the environment as relevant to the Peace Prize.

The above statement indicates the extent to which the areas of global concern can be stretched by the Nobel Committee. Unlike the Nobel Prize in Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature as well as the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, which seem to have defined boundaries, the Peace Prize is almost without borders. The open-ended approach and readiness to confer the award to any individual or organization to highlight any issue of global, regional or local concern as of utmost importance at any point of time for the entire humanity may have merit of its own. However, it is also likely that the selection is made to ensure that it doesn’t cause a radical upset in the rules of power and governance games.

For instance, the Nobel Committee’s decision to offer the Peace Prize to Kissinger in 1973 and deny the same to Galtung during the following 50 years (1973-2023), like its unwillingness to award the prize to Mahatma Gandhi, indicates that sometimes the Prize may not be given to the most deserving candidates because of the fear that the rules of the power game may be crucially upset. The discussion below elaborates this point and suggests that certain awards were conferred without following Nobel’s will in letter and spirit.

Alfred Nobel, a Swedish engineer and chemist, owner of 355 patents and an industrialist who had built some 90 factories and companies in 20 countries, was an amazing internationalist and philanthropist. Signing his will in 1895, he set aside a substantial part of his wealth to fund five prizes in the fields of physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature, and peace to those ‘who, during the preceding year’ conferred ‘greatest benefit on mankind.’

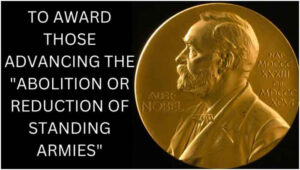

His will says that the proposed peace prize would go to ‘the person who shall have done the most or the best work for brotherhood between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.’ While the prizes for physics and chemistry were to be awarded by the Swedish Academy of Sciences, that for physiological or medical works by the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, that for literature by the Academy in Stockholm, and that for ‘champions of peace’ by a committee of five members of the Norwegian Parliament-Storting – to be elected by the House itself.

In other words, all the awards excepting peace are conferred by Swedish institutions, whose selection committees comprise leading experts in the relevant fields and whose recipients are usually distinguished educators, scholars, scientists and writers. In contrast, the final selection for the conferment of the Nobel Peace Prize is made by five sitting members of the Norwegian parliament, who belong to different political parties and are selected by the parliament. Over the years, the decision for the award has often been censured on one ground or the other.

For instance, the Norwegian Nobel Committee is criticized for often deviating from Nobel’s will, not focusing on the challenge of abolishing or reducing standing armies, showing little respect for international peace congresses held from time to time, insulting the peace visionaries and peace academics by not selecting them for the award, presenting the prize to undeserving persons occupying high position in the governments or international organizations, and stretching or contracting the eligibility and selection criteria to confer the award on less deserving persons.

According to Norwegian lawyer and peace activist, Fredrik Heffermehl, the prizes offered to UN agencies and other humanitarian prizes such as Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders) and International Red Cross, though praiseworthy for their contribution to the alleviation of suffering, ‘do not strive actively and as a matter of principle against war itself.’ He devotes a full chapter of his book to discuss the political and corporate control of the prize since 1990 and observes elsewhere in the book:

The following awards were so distant from Nobel’s idea of ‘Champions of Peace’ that they must be considered serious mistakes: Yasser Arafat, Shimon Peres, and Yitzhak Rabin (shared, 1994); Anwar al-Sadat and Menachem Begin (shared, 1978); Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho (shared, 1973); George C Marshall (1953), Eliha Root (1912); and Theodore Roosevelt (1906).

Keeping the above in view, the following discussion on the life and works of Henry Kissinger and Johan Galtung attempts to understand why Kissinger was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize and Galtung was denied the same.

TO READ FULL PAPER Download PDF File (16 pp):

Henry Kissinger, Johan Galtung and the Nobel Peace Prize

______________________________________________

Vol. 77 No. 2-3 (20 Aug 2024): Pakistan Horizon

Prof. Syed Sikander Mehdi is the former chairperson of the Department of International Relations at the University of Karachi. Educated at the University of Dhaka and Australian National University, he is a leading peace educator being the first to introduce courses on peace studies in the public and private universities of Pakistan. His works on culture of peace, violence/nonviolence, nuclear weapons, forced migration, and on museums for peace have been published in Pakistan and abroad. Email: sikander.mehdi@gmail.com

Prof. Syed Sikander Mehdi is the former chairperson of the Department of International Relations at the University of Karachi. Educated at the University of Dhaka and Australian National University, he is a leading peace educator being the first to introduce courses on peace studies in the public and private universities of Pakistan. His works on culture of peace, violence/nonviolence, nuclear weapons, forced migration, and on museums for peace have been published in Pakistan and abroad. Email: sikander.mehdi@gmail.com

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER STAYS POSTED FOR 2 WEEKS BEFORE BEING ARCHIVED

Tags: Conflict Analysis, Gandhi, Henry Kissinger, Johan Galtung, Nobel Peace Prize, Nobel's Will, Peace Research, Peace Studies

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 18 Nov 2024.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Henry Kissinger, Johan Galtung and the Nobel Peace Prize, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

4 Responses to “Henry Kissinger, Johan Galtung and the Nobel Peace Prize”

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER:

I was also nominated – twice. in 2008 and 2014 – for the Nobel Peace Prize and it didn’t take me more than five second to understand why the Nobel Committee were not interested in awarding me the “Peace” Prize. For the same reason they did not award it to dear Johan Galtung.

Henry Kissinger, Barack Obama, Yasser Arafat, Shimon Peres, Itzhak Rabin deserved the Nobel PEACE Prize because they all promoted WARS.

The President of Ethiopia, Ahmed Abiy, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 has spent much of the 1,1 million dollars in organizing civil wars in his own country.

Read the book about the Nobel Peace Award by Norwegian Fredrik S Heffermehl, to understand why the more Peace Awards we give, the more wars we have

Dear Prof. Syed Sikandar Mehdi,

Following my message to you on Monday, here is an article that will explain clearly to you why the Nobel Peace Committee promotes warmongering politicians. Norway is a country that has historically teamed with violence. Norway were the staunchest allies of Hitler and Nazism during WWII, and that was nearly 40 years AFTER the Nobel Peace Prize had been established!

France, Germany, UK, US make Norway’s billion-dollar frigate shortlist

By Rudy Ruitenberg

Nov 19, 2024, 05:13 PM

PARIS — Norway has narrowed the choice of possible partner countries for its future frigate program to France, Germany, the U.K. and the U.S., and plans to start talks with those countries’ governments about setting up a strategic partnership.

The program to buy at least five and possibly six frigates will represent Norway’s biggest defense investment ever, surpassing the acquisition of F-35 fighter jets, Defence Minister Bjørn Arild Gram said in a briefing on Tuesday. The country plans to make a final decision on a future strategic partner in 2025.

Norway is looking to join an existing frigate program to speed up fielding, thereby obviating upgrade investments in the country’s existing Fridtjof Nansen-class frigates. All major naval forces within NATO are in the process of adding new frigates, and Norway said it wants to establish a strategic partnership with a close ally rather than just buy a stand-alone vessel type.

“The new frigates represent the largest acquisition planned for the Norwegian armed forces in the coming years,” Gram said.

The country plans to invest several hundred billion Norwegian kroner in its navy, as well as significantly increase operating budgets and personnel, according to Gram. One hundred billion kroner is equivalent to around US$9.1 billion.

Norway is an important maritime state within NATO, and the High North is the country’s most strategic area of interest, important to both Norway and the alliance, Gram said. The ambition is for the Royal Norwegian Navy to be able to operate continuously in the ocean areas off Norway, according to the minister.

Defense officials envision a strategic frigate partnership that includes joint acquisition, operation and maintenance, as well as continuous development and upgrades of the ships during their service life. Gram said the new vessels will require upgrade and support for several decades, and Norway is looking for a partner that will commit for the entire service life of the future frigates.

The country isn’t just considering the capabilities of each potential partner country, but also coinciding strategic interests, including in the High North, according to the minister.

France started sea trials of its first Defense and Intervention Frigate this year, with another four ships planned, while Germany laid the keel for the first of four F126 frigates. The U.S. is constructing its first Constellation-class frigate, based on the French-Italian FREMM multi-mission frigate, although that program has run into delays. Meanwhile, the U.K. has seven frigates under construction, including four Type 26 anti-submarine warfare vessels and three Type 31 frigates.

The four countries are working on significantly different-sized vessels, from France’s brand-new FDI frigate displacing 4,500 metric tons, to Germany’s F126 frigate that will displace around 10,000 tons. Norway’s current Fridtjof Nansen-class warships, built by Spain’s Navantia, displace around 5,200 tons fully loaded.

Norway has a longstanding maritime cooperation with France, and while the French have a more global focus than the Norwegians, they’ve shown increasing interest in the High North, the defense minister said. The U.K. and Norway also have particularly close security and defense ties, and the Royal Navy has long been a main partner for the Norwegian forces, according to Gram.

The Nordic country also has security ties with Germany, with cooperation traditionally mainly within the land domain, though the countries are cooperating on submarines and anti-ship missiles, Gram said. Meanwhile, the U.S. is Norway’s most important ally, cooperating in all domains with a focus on the North Atlantic, according to the minister.

A key consideration in the final decision will be the ability for Norwegian technology and industry to contribute to both development and sustainment of the future frigate, according to Gram.

The Norwegian government in 2023 reached out to 11 countries with frigate programs, which in addition to the four nations picked for further talks included Australia, Canada, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and South Korea, according to Gram. The frigate program was included in the country’s long-term defense plan proposed in April.

It is an utter disgrace that Johan Galtung was never awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Just as it was an utter disgrace that Gandhi never received it either. But then it’s only a peace prize in name, so it’s fairly understandable Norway didn’t entertain the thought of giving the price to one of the planet’s most deserving persons. The Nobel Peace Prize is pretty much a foreign policy tool these days, and it shows.

It is really very unfortunate that a peaceful and highly respected country like Norway is involved in arms trade and militarybuilding. It strengthens the widely held viewpoint that the Norwegian government and the establishment often influence the decision-making process for the award of Nobel Peace Prize. There couldn’t have been any other reason for not awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to Galtung. Peace scholars and peace journalists should be encouraged to expose the governments and establishments of to so-called democratic and peaceful countries, which are themselves fueling arms race and arms trade.

The Nobel Peace Prize may be a peace prize in name only, but it has global impact. As such, the peace scholars and peace media people should join hands and raise their voices if and when a Nobel Peace Prize is offered to an undeserving person or organization. Equally importantly, new peace prizes, more credible peace prizes, need to be instituted to highlight and celebrate the role of peace academics and peace journalists to peace promotion and peacebuilding.