Albert Camus on Strength of Character and How to Save Our Sanity in Difficult Times

INSPIRATIONAL, 23 Dec 2024

Maria Popova | The Marginalian – TRANSCEND Media Service

In 1957, Albert Camus (November 7, 1913–January 4, 1960) became the second youngest laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature, awarded to him for work that “with clear-sighted earnestness illuminates the problems of the human conscience in our times.” (It was with this earnestness that, days after receiving the coveted accolade, he sent his childhood teacher a beautiful letter of gratitude.)

In 1957, Albert Camus (November 7, 1913–January 4, 1960) became the second youngest laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature, awarded to him for work that “with clear-sighted earnestness illuminates the problems of the human conscience in our times.” (It was with this earnestness that, days after receiving the coveted accolade, he sent his childhood teacher a beautiful letter of gratitude.)

More than half a century later, his lucid and luminous insight renders Camus a timeless seer of truth, one who ennobles and enlarges the human spirit in the very act of seeing it — the kind of attentiveness that calls to mind his compatriot Simone Weil, whom he admired more than he did any other thinker and who memorably asserted that “attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.”

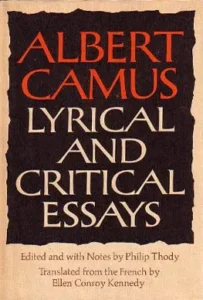

Nowhere does Camus’s generous attention to the human spirit emanate more brilliantly than in a 1940 essay titled “The Almond Trees” (after the arboreal species that blooms in winter), found in his Lyrical and Critical Essays (public library) — the superb volume that gave us Camus on happiness, despair, and how to amplify our love of life. Penned at the peak of WWII, to the shrill crescendo of humanity’s collective cry for justice and mercy, Camus’s clarion call for reawakening our noblest nature reverberates with newfound poignancy today, amid our present age of shootings and senseless violence.

At only twenty-seven, Camus writes:

We have not overcome our condition, and yet we know it better. We know that we live in contradiction, but we also know that we must refuse this contradiction and do what is needed to reduce it. Our task as [humans] is to find the few principles that will calm the infinite anguish of free souls. We must mend what has been torn apart, make justice imaginable again in a world so obviously unjust, give happiness a meaning once more to peoples poisoned by the misery of the century. Naturally, it is a superhuman task. But superhuman is the term for tasks [we] take a long time to accomplish, that’s all.

Let us know our aims then, holding fast to the mind, even if force puts on a thoughtful or a comfortable face in order to seduce us. The first thing is not to despair. Let us not listen too much to those who proclaim that the world is at an end. Civilizations do not die so easily, and even if our world were to collapse, it would not have been the first. It is indeed true that we live in tragic times. But too many people confuse tragedy with despair. “Tragedy,” [D.H.] Lawrence said, “ought to be a great kick at misery.” This is a healthy and immediately applicable thought. There are many things today deserving such a kick.

In a sentiment evocative of the 1919 manifesto Declaration of the Independence of the Mind — which was signed by such luminaries as Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein, Rabindranath Tagore, Jane Addams, Upton Sinclair, Stefan Zweig, and Hermann Hesse — Camus argues that this “kick” is to be delivered by the deliberate cultivation of the mind’s highest virtues:

If we are to save the mind we must ignore its gloomy virtues and celebrate its strength and wonder. Our world is poisoned by its misery, and seems to wallow in it. It has utterly surrendered to that evil which Nietzsche called the spirit of heaviness. Let us not add to this. It is futile to weep over the mind, it is enough to labor for it.

But where are the conquering virtues of the mind? The same Nietzsche listed them as mortal enemies to heaviness of the spirit. For him, they are strength of character, taste, the “world,” classical happiness, severe pride, the cold frugality of the wise. More than ever, these virtues are necessary today, and each of us can choose the one that suits him best. Before the vastness of the undertaking, let no one forget strength of character. I don’t mean the theatrical kind on political platforms, complete with frowns and threatening gestures. But the kind that through the virtue of its purity and its sap, stands up to all the winds that blow in from the sea. Such is the strength of character that in the winter of the world will prepare the fruit.

Elsewhere in the volume, Camus writes: “In the depths of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer.” Each time our world cycles through a winter of the human spirit, Camus remains an abiding hearth of the invisible summer within us, his work a perennial invitation to reinhabit our deepest decency and live up to our most ennobled nature.

Complement this particular excerpt from the thoroughly elevating Lyrical and Critical Essays with Nietzsche on what it really means to be a free spirit and Susan Sontag on how to be a moral human being, then revisit Camus on happiness, unhappiness, and our self-imposed prisons and our search for meaning.

_______________________________________

My name is Maria Popova — a reader, a wonderer, and a lover of reality who makes sense of the world and herself through the essential inner dialogue that is the act of writing. The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first 15 years) is my one-woman labor of love, exploring what it means to live a decent, inspired, substantive life of purpose and gladness. Founded in 2006 as a weekly email to seven friends, eventually brought online and now included in the Library of Congress permanent web archive, it is a record of my own becoming as a person — intellectually, creatively, spiritually, poetically — drawn from my extended marginalia on the search for meaning across literature, science, art, philosophy, and the various other tendrils of human thought and feeling. A private inquiry irradiated by the ultimate question, the great quickening of wonderment that binds us all: What is all this? (More…)

My name is Maria Popova — a reader, a wonderer, and a lover of reality who makes sense of the world and herself through the essential inner dialogue that is the act of writing. The Marginalian (which bore the unbearable name Brain Pickings for its first 15 years) is my one-woman labor of love, exploring what it means to live a decent, inspired, substantive life of purpose and gladness. Founded in 2006 as a weekly email to seven friends, eventually brought online and now included in the Library of Congress permanent web archive, it is a record of my own becoming as a person — intellectually, creatively, spiritually, poetically — drawn from my extended marginalia on the search for meaning across literature, science, art, philosophy, and the various other tendrils of human thought and feeling. A private inquiry irradiated by the ultimate question, the great quickening of wonderment that binds us all: What is all this? (More…)

Go to Original – themarginalian.org

Tags: Albert Camus, Friedrich Nietzsche, Inspirational, Wisdom

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.