Crush and Burn: A History of the Global Crackdown on Ivory

ANIMAL RIGHTS - VEGETARIANISM, 3 Feb 2014

Svati Kirsten Narula – The Atlantic

Hong Kong is the latest government to publicly destroy its stockpile of the prized material.

It’s an unlikely and ambitious government project: Over the next two years, Hong Kong will embark on the world’s largest ivory burn, setting 28 tons of illegally harvested tusks aflame to signal a shift in its valuation of elephants. As National Geographic reports, this is actually the latest in a string of public ivory disposals around the world. China crushed six tons of tusks and ivory ornaments on January 6; the United States smashed six tons in November 2013; and the Philippines burned five tons in June 2013, making history as the first “ivory-consuming nation” to destroy almost all of its national stock. Gabon burned its stockpile in June 2012.

All this comes after elephant poaching and ivory smuggling reached unprecedented levelsin 2011, a year in which at least 25,000 African elephants were killed for their tusks, according to a statistician involved in monitoring illegal elephant killings. By early 2013, terms like “blood ivory” and “African Elephant Crisis” were on the lips of conservationists and politicians alike.

That’s about when the U.S. embarked on a period of frenzied activity to combat the ivory trade. In July, President Obama established a task force on wildlife trafficking and committed $10 million for anti-poaching and anti-smuggling efforts in Africa. A few months later, Hillary Clinton announced a separate $80-million, three-year program aimed at “stamping out” elephant poaching and the ivory trade. Claiming that African forest elephants could be extinct within 10 years unless the poaching stopped, Clinton characterized the situation not only as “an ecological disaster” but also as a threat to political and economic stability throughout Africa and Asia. In November, amid hundreds of cameras and reporters, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service pulverized six tons of elephant ivory—a stockpile accumulated over 24 years of domestic law-enforcement seizures.

China soon followed suit—a particularly big deal because the country has been the world’s largest consumer of illegal ivory for the past decade. And now Hong Kong is getting in on the action as well, as are some European countries. Still, it’s worth keeping in mind that ivory-burning isn’t an entirely new trend. Kenya took the first major stand against the ivory trade back in 1989 by torching 12 tons of elephant tusks in Nairobi National Park. The country’s president, Daniel arap Moi, lit the flames himself. “I appeal to people all over the world to stop buying ivory,” he told the press.

The gesture came at a time when elephants were not yet classified as endangered, and the United States and Tanzania were just beginning to float the idea of banning ivory trading. The Kenyan government recognized that preserving the country’s elephants could be essential for preserving tourism. Poaching had gotten so bad that some wild areas looked more like elephant graveyards, littered with piles of bleached bones, than living habitats.

A few months later, much to Kenya’s credit, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), a multilateral treaty, implemented a global ban on ivory trading. It worked—for a little while, at least. Even though a handful of countries (Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) claimed exemptions to the ban, ivory prices plummeted and the number of elephants in Africa slowly increased over the next 10 years.

Then, in 1999, CITES allowed Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe to sell 50 tons of stockpiled ivory to Japan—a “one-time,” “experimental” sale. But then China wanted to buy some, too (and Japan wanted more). Before allowing another sale, though, CITES decided to monitor the after-effects of the 1999 transaction: Had elephant poaching or smuggling gone up as a result? As National Geographic reporter Bryan Christy explains, this may not have been the smartest study ever conducted. (Christy has been investigating illegal wildlife trafficking for years, and his coverage of the ivory trade is essential reading.)

In Christy’s words, “CITES had approved the sale and had then set about constructing a way to gauge its impact, which is a bit like pushing the button to test the first atomic bomb and then building a device to measure the explosion.” CITES tried to count elephant carcasses and monitor seizures of smuggled ivory—but those are both difficult things to do, and neither one provides a reliably accurate measure of whether more or less poaching and smuggling is occurring.

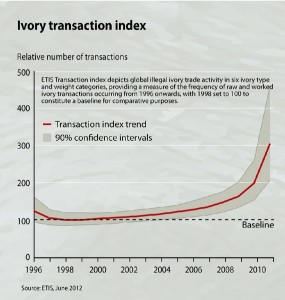

The graph below presents some of the data collected by CITES, in collaboration with other international organizations, to make inferences about illegal ivory trafficking based on large-scale law-enforcement seizures of smuggled ivory.

“Smugglers don’t file sales reports,” writes Christy, so CITES uses ivory seizures as a “proxy” for smuggling activity. In the graph above, 1998 is the “baseline” because that’s the year before the “experimental” ivory sale to Japan. The chart shows that the frequency of illegal trafficking roughly tripled between 1998 and 2011. But it’s possible that it actually quadrupled, or only doubled. As Christy puts it:

Even as a proxy, seizures are tricky. They accurately tell you only the bare minimum of illegal activity going on in a country, and there’s a lot they can’t tell you. More ivory seizures in one year can mean that smuggling has increased, or that law enforcement is working harder, or both. Fewer seizures can mean what you might hope, but they can also mean that law enforcement is on the take. Big-time smugglers have connections in local wildlife departments, customs offices, and freight-forwarding and transportation companies that enable them to move multi-ton shipments from one country to another. (In the Philippines, for example, ivory traders I met accused customs officers of seizing illegal ivory only when someone hadn’t made a payoff.) Worst of all, a seizures-based system rewards countries for confiscating ivory, when what they really need to do is follow smuggled ivory up the demand chain to the kingpins, a reason good investigators consider seizures to be bad law enforcement.

One element of the “transaction index” that’s probably accurate is the dramatic increase in trafficking between 2009 and 2011. That’s because in 2008, CITES let Chinese and Japanese traders buy over 100 tons of ivory in another “strictly supervised,” “one-time” sale. CITES, not to mention a host of other organizations that endorsed the sale, believed this move could curb poaching. The Chinese, so the thinking went, would flood their domestic market with low-priced, legal ivory, which would presumably undercut the black market. Instead, China raised ivory prices and limited the supply by releasing just a few tons of the legal ivory each year. Rather than undercutting the black market, the Chinese government was outperforming it. As a result, smuggling actually increased.

Christy later suggested substituting “cocaine” for “ivory” in order to understand the absurdity of the China sale:

[T]aking the U.S. to be the China of cocaine consuming nations, imagine you are an American drug trafficker. CITES has just sold 100 tons of cocaine to the U.K. and the U.S. Your cocaine is of course indistinguishable from that sold by government-approved shops now opening in major American cities. The government’s selling price is higher than yours. Do you stop cocaine trafficking? Or do you tell all your friends and your children to join you, anticipating an ever expanding future?

In an article titled “Elephants Are Not Diamonds,” the biologist Katarzyna Nowak also attacked the sale, and the notion of a future “legal” ivory trade, albeit with different logic. “To view ivory as a commodity like diamonds or gold is oblivious of the underlying principles of population biology, lacking appreciation of sustainability, and ignoring the corruption and ethics associated with such exploitation,” she wrote.

The CITES Secretariat had recently commissioned a report, Decision-Making Mechanisms for a Process of Trade in Ivory, which considered the merits of legalizing the ivory trade again in order to reduce poaching and thus protect elephants. The study’s authors proposed a trading mechanism for ivory based on the De Beers model for the diamond market. But unlike diamonds, Nowak argued, ivory tusks are connected to living, breathing animals that shape their environment, influence whole ecosystems, and feel suffering.

Elephant tusks are not diamonds; elephant numbers are rapidly diminishing and ivory is becoming synonymous with corruption and organized crime including money laundering, drugs, human and arms trafficking. In Africa, this trade fuels poverty, insecurity, and armed conflicts, putting people’s lives at risk and threatening economic options like tourism as well as causing irreparable harm to Africa’s environment by removing a major ecosystem engineer.

There never has been and never will be a sustainable or ethical ivory trade, concluded Nowack. “The entire CITES system risks total discredit” unless it supports a total moratorium on ivory sales and implements the destruction of international ivory stockpiles—to demonstrate that ivory is only an asset when it is on living elephants.

Even though Christy argues for the same thing—a total moratorium—he is quick to acknowledge that the ivory trade isn’t just about elephants. It’s also about religion. As Oliver Payne, Christy’s editor, explains, the journalist soon shifted his attention away from identifying ivory kingpins and crime syndicates in ivory-producing countries, and “toward consumer countries, such as the Philippines, where religious uses of ivory are deeply entrenched in the culture.”

Hundreds of carved religious ornaments were among the six tons of ivory crushed by the U.S. in November 2013. (Rick Wilking/Reuters)

So what can be done about the ivory trade?

”To stop the poacher, the trader must be also be stopped and to stop the trader, the final buyer must be convinced not to buy ivory,” Kenya’s President Moi said in 1989. That is the very same logic world leaders are employing to promote today’s ivory disposals. And that’s worrying: If we’re using the same logic today that we used a quarter-century ago, how can we expect different results?

When Bryan Christy attended the big U.S. ivory crush in Colorado a few months ago, he showed up with that question in mind. “Stop the Killing, Stop the Trafficking, Stop the Demand”—the slogan of the Clinton Global Initiative campaign to save the elephants—”is so patently obvious that I find it insulting,” Christy wrote. “Supply, shipment, and consumption are the cornerstones of every form of international trade. To present them as a fresh perspective on an old problem is to trigger my worst fears as a criminal investigator: Nothing will change.”

But Christy was pleasantly surprised. The government announced a million-dollar bounty on the head of a major wildlife crime syndicate. He heard that the practice of bribing officials in China with luxury items—including ivory—was becoming less common. A representative from Kenya called America’s actions “a lesson for China.” And as he left the venue, Christy overheard people “discussing the possibility of a nationwide program for people to turn in legal ivory they have in their homes but don’t want to keep in light of today’s elephant slaughter.”

Yes, we may be back where we were a quarter-century ago. But we know more about the ivory trade now than we did then, and a lot has changed since 1989—including the way news spreads on television and the Internet. This is the world’s second chance to save its elephants. And this time around, symbolic ivory purges may be one of the best ways to do it.

Copyright © 2014 by The Atlantic Monthly Group. All Rights Reserved.

Go to Original – theatlantic.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

ANIMAL RIGHTS - VEGETARIANISM: