Should Journalists Trust Themselves to Figure Out Which Sources Are Trustworthy?

MEDIA, 8 Sep 2014

Reg Chua - (Re)Structuring Journalism

People Like Us

Who should you trust? (Or, for all you pedants out there, whom should you trust?)

It’s an important question for all of us, not least when you’re buying a used car (and believe me, I know.)

But it’s probably even more important for journalists, who talk to strangers on a regular basis and need to make snap judgments about how much faith we should have in what they say.

So here’s the bad news: You shouldn’t trust yourself to figure out who you should trust.

At least that’s the case if I understand Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People, a very interesting book by social psychologists Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greenwald, correctly. Blindspot is a good book (although Mahzarin is an even better lecturer; she recently gave a great talk to a number of Thomson Reuters folks) that focuses on the biases and prejudices – “mindbugs,” she calls them – that we have, but that we don’t know we have.

Don’t believe me (or rather, her)? Check out the Harvard Implicit Association Test, which tracks, via the length of time it takes for you to run through a series of matching tests, how strongly you associate one group with a set of traits – for example, female names with domestic terms, as opposed to men and work issues, or white faces with Americaness vs. non-whites. Try the test(s): They’re both scary and enlightening. And if you’re like me, you’ll take them a couple of times because you don’t like how the results turned out.

Alas, the results don’t change. At least not very much, and not without a fair amount of intervention.

Which is another way of saying that we all have biases, many of which we’re unaware of, and that we act on them unconsciously. That’s not to say we’re racist or sexist, or that we knowingly discriminate against groups we don’t like. But it does mean we’re often oblivious to the many small and large ways our biases tilt our judgement.

Consider that in 1970 women comprised less than less than 10% of major orchestras in the US and fewer than 20% of new hires. As Mahzarin recounts in her book, back then auditions for new members were conducted in front of a team of seasoned musicians, often from that orchestra. You’d expect that they had well-trained ears, able to select the best candidates. And they largely picked men.

But then an interesting thing happened when they started auditioning candidates behind a curtain, and taking pains not to let the panel know if it was a man or a woman was playing. More women won spots. And after two decades of what’s now a widespread practice,

…the proportion of women hired by major symphony orchestras doubled – from 20 percent to 40 percent. In retrospect it is easy to see that a virtuoso = male stereotype was an invalid but potent mindbug, undermining the orchestra’s ability to select the most talented musicians.

(Here’s another study of the same phenomena, with different numbers but the same conclusion.)

What does that mean for our ability to spot people who seem to be more (or less) trustworthy or truthful? Or more precisely, what does it mean for our bias towards trusting some types of people more than others? What mindbug do we have that says XXX = trustworthy?

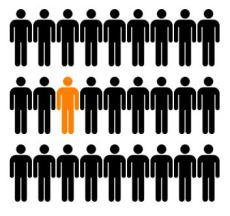

It may come down to how much we identify with them. Brain imagining scans show that we use one part of our brains to think about people we believe are more like us, and another part to deal with people we think are different from us. Researchers came up with profiles for fictional people who were similar to and different from experimental subjects; then they looked at the subjects’ brain activity when asked simple questions about the fictional people – eg, how likely do you think is it that John will go home for Thanksgiving?

The brain, it turns out, engages two different clusters of neurons in thinking about other people, and which cluster gets activated depends on the degree to which one identifies with those others.

Does that mean that, in practice, we treat people we think are different from us differently? It’s not clear from the brain imaging research, but it’s at least clear that we use a different part of our brain when we deal with them. And that should be a warning to journalists, who have to deal with a broad range of people – many of whom we don’t like, personally – and try to treat them all equally, at least in terms of the information they give us.

And the issue may be less about discriminating against people we dislike – I’d like to think we’re reasonably sensitive to that – but more about the additional credence we give people we do identify with.

Mahzarin gives an example of a college professor who hurt her hand and had to go to the university ER; the attending physician gave her professional but perfunctory help until someone mentioned her position at the university. The doctor quickly pulled in a specialist and escalated the level of her care once he identified her as a colleague.

The importance of (the professor’s) story is that by capturing not just acts of commission but acts of omission, we expand our sense of how hidden bias operates. It allows us to see that the people responsible for such acts of omission are, like the doctor who is the main actor in this story, by and large good people who believe that helping is admirable.

In other words, the doctor didn’t discriminate against the professor by giving her adequate care; but he then did discriminate for her once he realized her position.

I remember, years ago, being on a panel and being asked by a journalism student about whether it was alright to be friends with military and police personnel who she had to cover (this was pre-9/11, in the days before the military was much less visible in American society). The trouble with the question is that, as long as we see groups like that – or any group, whether evangelical Christians or gays and lesbians – as separate from “us” and our friends, we fire up a different part of our brain, and it’s hard to give their testimony as fair a shake as we should.

So what can we do to combat unconscious bias? It’s tough. We can take the IATs until we’re blue in the face, but it won’t change very much. Still, it’s important to know what our biases are; awareness is a good first step, and helps us be more conscious about compensating for our biases. We can get out more, and talk to, and get to know, a broader range of people; the more women we see as virtuoso musicians, the weaker the mindbug that virtuoso = male becomes. We can depend less on human testimony – which is often flawed anyway – and expand out to look at documents and data – also flawed in their own way, but at least in different ways.

Because all of this is important. As Mahzarin notes, one of the IATs tests the association of African Americans with weapons, and it’s a particularly strong one for many people. And as the events of Ferguson have show us,

In terms of “guilt by association,” a Black = weapons stereotype is particularly consequential when it plays out in the interaction between citizens and law enforcement.

____________________________

Reg Chua has been a journalist for more than a quarter-century; he’s currently Executive Editor, Editorial Operations, Data and Innovation at Thomson Reuters. Prior to that, he was Editor-in-Chief of the South China Morning Post and had a 16-year career at The Wall Street Journal.

(Re)Structuring Journalism explores the evolution of information in a digital age and how we need to fundamentally rethink what journalists do and what they produce. And it proposes one possible solution: Structured Journalism.

Go to Original – structureofnews.wordpress.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.