Move Over, NATO and IMF: Eurasia Is Coming

BRICS, 13 Oct 2014

Conn Hallinan – Foreign Policy In Focus

A thousand poles are blooming as new international blocs like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the BRICS Development Bank emerge to challenge Western economic and military hegemony.

At the very moment that the Americans and their allies are trying to squeeze Russia and Iran with a combination of economic sanctions and political isolation, alternative poles of power are emerging that soon may present a serious challenge to the U.S.-dominated world that emerged from the end of the Cold War.

This past summer, the BRICS countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—created an alternative to the largely U.S.-controlled World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) added 1.6 billion people to its rolls.

The BRICS’ construction of a Contingent Reserve Arrangement will give its members emergency access to foreign currency, which might eventually dethrone the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. The creation of a development bank will make it possible to bypass the IMF for balance-of-payment loans, thus avoiding the organization’s onerous austerity requirements.

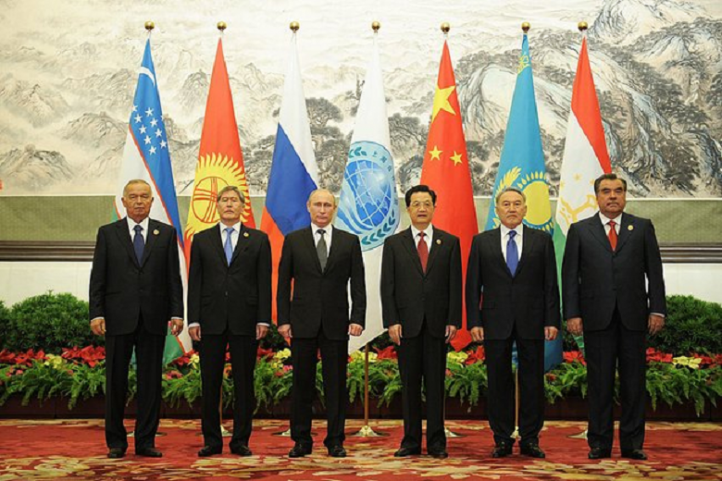

Less than a month after the BRICS’ declaration of independence from the current strictures of world finance, the SCO—which includes China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan—approved India, Pakistan, Iran, and Mongolia for membership in the organization. It was the single largest expansion of the economic cooperation and security-minded group in its history, and it could end up diluting the impact of sanctions currently plaguing Moscow over the Ukraine crisis and Tehran over its nuclear program.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization began as the Shanghai Five in 1996, and five years later became the SCO. Even before the recent additions, SCO represented three-fifths of Eurasia and 25 percent of the world’s population.

Overlapping Agendas

A major focus of the SCO is security, although the countries involved have different agendas about what that exactly means.

Russia and China are determined to reduce U.S. and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) presence in Central Asia to what it was before the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. The SCO has consistently rebuffed U.S. requests for observer status, and has pressured countries in the region to end U.S. basing rights. The United States was forced out of Karshi-Khanabad in Uzbekistan in 2005, and from Manas in Kyrgyzstan in 2014.

“At present, the SCO has started to counterbalance NATO’s role in Asia,” says Aleksey Maslov, chair of the Department of Asian Studies of the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. And the new members, he says, want in to safeguard their interests.

Moscow and Beijing may not agree on a number of issues—in 1969 they came to blows over a border dispute—but they are on the same page when it comes to limiting Washington’s influence in their respective backyards.

Chinese Defense Minister Gen. Chang Wanquan said last year that “China is ready to work with Russia to…expand the scope of bilateral defense cooperation.” In August, Russia’s Chief of Staff Gen. Valery Gerasimov declared that “Russia is ready to make joint efforts with China to lift the relationship to a new high.” China has been supportive of Russia in the Ukraine crisis.

For Iran, SCO membership may serve as a way to bypass the sanctions currently pounding the Iranian economy. Russia and Iran signed a memorandum in August to exchange Russian energy technology and food for Iranian oil, a move that would violate U.S. sanctions. But Moscow—already weathering sanctions that have weakened its own economy—may be figuring that there is little more the U.S. government can do to Russia and still keep its European allies on board. Russian counter-sanctions on the European Union (EU) have shoved a number of European countries back into recession . The EU, meanwhile, is worried that Russia will turn east and Europe will lose much of its Russian market share.

To a certain extent, that is already happening. When the 2,500-mile “Power of Siberia” pipeline is completed in 2018, it will supply China with about 15 percent of its natural gas. Russia’s Rosneft and China’s National Petroleum Corporation are jointly exploring oil and gas reserves in the Arctic, meanwhile, and the Russians have also offered China a stake in the huge Vankor oil field in East Siberia. Since January 2014, some 30 percent of Russian oil exports have gone to Asia.

Tehran is reaching out to Beijing as well. Iran and China have negotiated a deal to trade Iran’s oil for China’s manufactured goods. Beijing is currently Iran’s number-one customer for oil. In late September, two Chinese warships paid a first-ever visit to Iran, and the two countries’ navies carried out joint anti-piracy and rescue maneuvers.

For India and Pakistan, energy is a major concern, and membership in the oil- and gas-rich SCO is a major plus. Whether that will lead to a reduction of tensions between New Delhi and Islamabad over Kashmir is less certain, but at least the two traditional enemies will be sitting down to talk about economic cooperation and regional security on a regular basis.

There are similar tensions between SCO members Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan over borders, and both countries, plus Tajikistan, have squabbled over water rights.

Most SCO members are concerned about security, particularly given the imminent departure of the United States and NATO from Afghanistan. That country might well descend into civil war, one that could have a destabilizing effect on its neighbors. Added to that is the U.S.-Arab intervention in Syria, a conflict that is raising yet another generation of mujahedeen that will someday reappear in their home countries—some of them SCO members—trained and primed for war.

From August 24 -29, SCO members China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan took part in “Peace Mission 2014,” an anti-terrorist exercise to “subdue” a hypothetical Central Asian city that had become a center for terrorist activity. The drill involved aircraft, 7,000 troops, armored vehicles, and drones. According to China’s military Chief of Staff, Fang Fenghui, it was aimed at the “three evil forces of terrorism, separatism, and extremism.”

The problem with General Fang’s definition of “terrorism” is that it can easily be applied to minorities or local groups with legitimate complaints about their treatment by SCO member governments.

China has come down hard on Turkic-speaking Uighurs in Xinjiang Province, for example, who have been resisting marginalization by China’s dominant ethnic group, the Han. Uighur scholar IIham Tohti was recently sentenced to life imprisonment for “separatist activity.”

Beijing has also suppressed demands for independence or more autonomy by Tibetans—whom it also labels “separatists” —even though China has no more a claim over Tibet than Britain did to India or Ireland. All of them were swept up by empires at the point of a sword.

New Centers of Power

The BRICS and the SCO are the two largest independent international organizations to develop over the past decade, but there are others as well.

In Latin America, Mercosur—an economic bloc that includes Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Venezuela—is the third largest trade grouping in the world. Associate members include Chile, Colombia, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru, while Mexico and New Zealand have observer status. The newly minted Union of South American Nations (USAN) includes every country in South America, including Cuba, and has largely replaced the Organization of American States (OAS), a Cold War relic that excluded Havana. While the United States and Canada are part of the OAS, they were not invited to join USAN.

What role these new organizations will play internationally is not clear. Certainly sanctions regimes will be harder to maintain because the SCO and the BRICS create alternatives. South Africa, for instance, announced that it would begin buying Iranian oil in the next few months, an important breach in the sanctions against Iran. But being in the same organization does not automatically translate into having the same politics on international questions.

The BRICS and the recent Israeli invasion of Gaza are a case in point. China called for negotiations. Russia was generally neutral (but friendly toward the Netanyahu government, in part because there are lots of Russians in Israel). India was silent—Israel is New Delhi’s number-one source of arms. South Africa was critical of Israel, and Brazil withdrew its ambassador.

In comparison, NATO was generally supportive of the Israeli actions, Turkey being the odd man out. There is more political uniformity among NATO countries than there is among SCO and BRICS nations, although there is growing opposition in the ranks of the European Union (EU) to Washington’s hardline approach on the Ukraine. The U.S. does $26 billion in trade with Russia, the EU $370 billion. Russia also supplies Europe with 30 percent of its natural gas, a figure that reaches 100 percent for countries like Finland. Most EU countries—the Baltic nations and Poland being the exceptions—see little advantage in a long, drawn-out confrontation with Russia.

These independent poles are only starting to develop, and it is hardly clear what their ultimate impact on international politics will be. But the days when the IMF, World Bank, and U.S. Treasury could essentially dictate international finances and intimidate or crush opponents with an avalanche of sanctions are drawing to a close.

The BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization are two nails in that coffin.

_________________________

Foreign Policy In Focus columnist Conn Hallinan can be read at www.dispatchesfromtheedgeblog.wordpress.com and www.middleempireseries.wordpress.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.