Russia and China Want to Radically Change How the Internet Is Used

MEDIA, 17 Aug 2015

15 Aug 2015 – Russia and China will maintain a unified front to challenge the West’s conception of the internet.

Efforts to fundamentally alter internet governance are likely to fail, but Moscow and Beijing will be able to extend government control on their respective domestic internet realms.

Economic conditions will force Moscow and Beijing to maintain aggressive domestic network security policies.

A Russian law regarding data localization of internet communications goes into effect September 1 with the stated intent of safeguarding Russian citizens from the growing threat of foreign interference, particularly from the US, in cyberspace.

The law effectively requires companies obtaining information online from Russian citizens to store that data on servers physically located in the country.

Initially, companies like Google, Facebook, or Twitter would be required to move or build data centers in Russia if they wish to conduct business online there, otherwise Russian internet users presumably would be blocked from accessing the company’s content.

Foreign technology industries and civic activists have opposed the law, which Russian President Vladimir Putin signed in July 2014, but it addresses Russia’s network-security concerns in several ways.

The law gives Russia another tool for controlling the flow of information within its borders to tamp down on dissidence. Moreover, the Kremlin wants to closely monitor the flow of information into and out of Russia through the internet to protect its internet space from foreign actors, whether state or nonstate.

The issue of data localization in Russia is a microcosm of the Kremlin’s overall effort to shape the standards, rules, architecture, and future development of the internet.

Russia and China are the most notable among the countries that want to challenge the de facto model of a decentralized collection of loosely structured committees and internet stakeholders agreeing to technical standards for the internet. The status quo of the internet, and particularly the prominence of US and other Western stakeholders, is an obstacle to the desired change in internet governance, but common network-security policies shared by countries such as China and Russia will be able to hold some sway over future global internet policies.

The effort revolves around a polarized view of governing the internet with either a multilateral model (with each country’s government dictating the rules) or a multistakeholder model (with all participants having an equal say in governing the current model).

Internet governance

Internet governance is broadly defined as the processes that affect how the internet is managed. The internet is the collection of networks of devices around the world that are voluntarily interconnected using some degree of shared standards and policies.

No single body dictates or enforces how the internet expands, which underlying technologies are used, or what rules govern the use of the global network, though international committees set critical standards, such as defining addresses at which individual devices can reach one another.

Since the internet began expanding rapidly, the irresistible and continually growing value it can provide to stakeholders, including countries, has forced most national governments to either accept the status quo of internet governance or attempt to form their own policies at the domestic level, risking international pushback. Of course, maintaining a network of devices separate from the internet is a common practice, particularly regarding security concerns in lower-level network operations.

However, national-level policies of nonparticipation, as largely practiced by North Korea, deprive a country’s industries of the economic opportunities the internet offers.

The internet architecture and the manner in which it is governed are still rooted in its country of origin, the US. Western technologies and industries, particularly from the US, dominate the internet’s current construct.

Moreover, the US government designed the governing model and retains influence over small yet critical functions, such as managing network addresses, which define the accepted standards of the internet community. However, this responsibility is in the process of moving from Washington to a private entity.

From the perspective of internet users, the abstract world of online activity is not necessarily tied to geographic and political boundaries, but it does rest on physical infrastructure inseparable from geography. As a result, every country adapts domestic and foreign policies incorporating the internet — policies that can affect the activities of internet stakeholders and users. Geopolitics is naturally interwoven into the evolution of these policies.

It is no surprise, then, that China and Russia are promoting network security and internet governance issues that reflect their geopolitical situations and that mirror international relations in other areas.

For example, just as the two countries’ membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) grouping serve to counter US economic, political, and military power, their similar visions of network security and internet governance serve to challenge what they perceive as a US-centric internet — one that also conflicts with their national security interests.

Russia and China are not alone in having their domestic and foreign policies challenged by participation in the internet. However, since the advantages of participating greatly outweigh the safety of isolation, they and other countries have had to continually manage the difficulties (such as China’s use of the so-called Great Firewall) that the internet presents. Now Moscow and Beijing are pushing for global internet standards that better suit their geopolitical needs, using network security as the impetus for change and greater authority in internet governance.

Russia cybersecurity

Washington’s approach to network security involves government agencies working with each other and with various stakeholders in the private sector to improve cyberdefense for all. In contrast, Russia’s approach has been to tighten government control over the information flowing both within its borders and between its internet space and the rest of the world.

Russia’s data-localization law is the Kremlin’s latest attempt to address its network-security concerns. The law has provoked some opposition, mainly from foreign technology companies concerned about the financial costs of compliance and from civic activists fearing the law’s use as a way to censor internet content in Russia.

The Kremlin has ameliorated some of these concerns; in early August, the government narrowed the definition of personal data, and roughly a month earlier the Kremlin assured Twitter that the information it obtains on its users is not considered personal data. Opposition to the law will not prevent its implementation; in fact, implementation was pushed forward from September 2016 to September 2015. However, the Kremlin’s capitulations illustrate the challenges that the existing internet governance model poses for governments seeking greater control over national network-security policies.

Russian President Vladimir Putin during his annual end-of-year news conference in Moscow, December 18, 2014, in which he discussed the issue of internet surveillance.

REUTERS/Maxim Zmeyev

As a means of curtailing resistance to domestic policies that could challenge internet and data access, Russia and other countries have sought overarching global policies regarding internet governance that better encourage such measures.

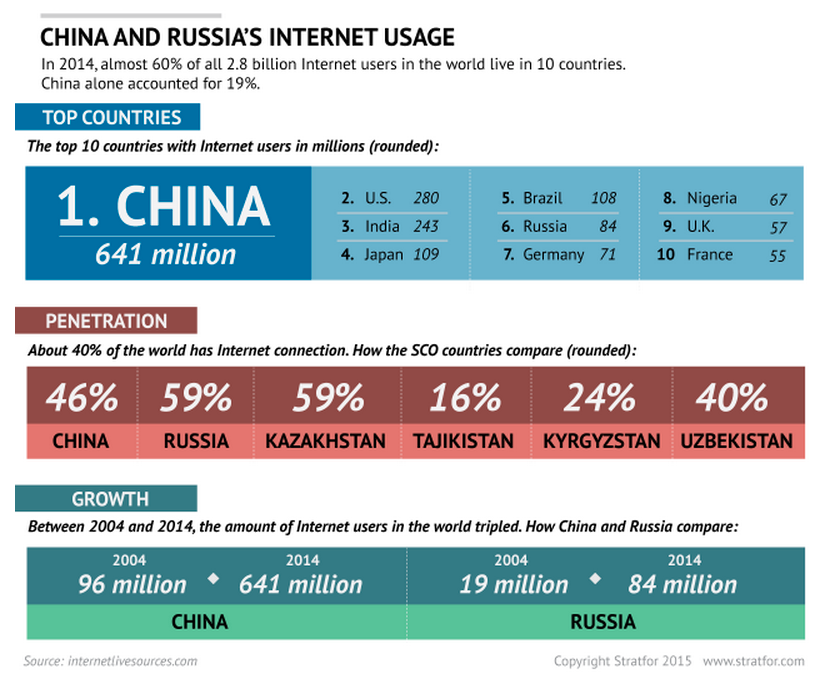

In January, Russia and the five other SCO members — China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan — submitted a document to the UN titled “The International Code of Conduct for Information Security,” to be circulated in the UN General Assembly. The document attempted to define the role of the state in information technology and emphasized an intergovernmental model of internet governance. It was also a minor revision to the initial document that Russia, China, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan submitted in September 2011, which Western UN members widely rejected.

Rapidly growing worldwide concerns about network security have bolstered Russia’s argument for more multilateral internet governance. The revelations from classified documents leaked by former US National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden highlighted the scale of US global cyber espionage, including some cases in which products from US technology industries were used to spy online.

Since the leaks, China has been working on implementing its own network-security laws and other national security policies that cover a much broader scope than Russia’s data-localization law, including enforcing the concept of internet sovereignty in legislation and banning foreign technologies in some cases for critical sectors.

China already employs much stricter measures than Russia regarding censorship and government control over its internet space. But China’s network-security strategy intersects with its economic goals and leverages the demand of its enormous population of internet users in implementing national policies to help defy internet stakeholder opposition.

Because Russia and China seek to impose similar views of governing the internet, their partnering in network security bolsters each country’s clout in shaping otherwise separate domestic internet regulations and gives them more potential influence over global policies.

The Chinese are watching their people’s internet use much closer than Russians are.

Reuters/David Gray

During Chinese President Xi Jinping’s May 8 visit to Moscow, Xi and Putin signed a pledge that their governments would not conduct cyberattacks against one another. Instead, they agreed to exchange network-security information between law-enforcement agencies and counter technology that threatens political and socioeconomic stability in their respective countries.

The agreement’s tactical impact, if any, on cyberwarfare and online criminal activity will depend on the extent to which the countries carry out the pact’s stated goals. However, effective cooperation under the agreement is not as important as their shared desires for more governmental control over the internet, and their ability to bolster each other’s goals in that area.

Likely changes in government control

The efforts of Russia and China to fundamentally alter the internet’s current governing model or wrest its architecture from Western influence is not likely to succeed in the foreseeable future. Opposition to any future domestic network-security policies could also hamper such measures. China already has had to backpedal on some policies, such as forcing its banking institutions to abandon foreign technologies, in the past year.

But their calls for multilateral internet governance and government control over network security likely will find some measure of success. China’s attempt to resist Western influence will certainly continue; that strategy is tied to Beijing’s economic ambitions to expand into high-tech industries. Russia will likely feel a growing need to control the exchange of information over networks in its territory as it prepares for potential unrest amid a steep economic decline. Global concerns about network security will provide both countries with a pretext to pursue their efforts.

Go to Original – businessinsider.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.