Nietzsche on How to Find Yourself and the True Value of Education

EDUCATION, 12 Oct 2015

Maria Popova, Brain Pickings – TRANSCEND Media Service

“No one can build you the bridge on which you, and only you, must cross the river of life.”

“Do you have the courage to bring forth the treasures that are hidden within you?” Elizabeth Gilbert asked in framing her catalyst for creative magic. This is among life’s most abiding questions and the history of human creativity — our art and our poetry and most empathically all of our philosophy — is the history of attempts to answer it.

“Do you have the courage to bring forth the treasures that are hidden within you?” Elizabeth Gilbert asked in framing her catalyst for creative magic. This is among life’s most abiding questions and the history of human creativity — our art and our poetry and most empathically all of our philosophy — is the history of attempts to answer it.

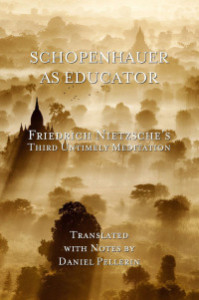

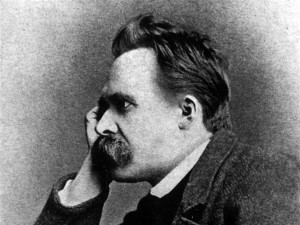

Friedrich Nietzsche (October 15, 1844–August 25, 1900), who believed that embracing difficulty is essential for a fulfilling life, considered the journey of self-discovery one of the greatest and most fertile existential difficulties. In 1873, as he was approaching his thirtieth birthday, Nietzsche addressed this perennial question of how we find ourselves and bring forth our gifts in a beautiful essay titled Schopenhauer as Educator (public library), part of his Untimely Meditations.

Nietzsche, translated here by Daniel Pellerin, writes:

Any human being who does not wish to be part of the masses need only stop making things easy for himself. Let him follow his conscience, which calls out to him: “Be yourself! All that you are now doing, thinking, desiring, all that is not you.”

Every young soul hears this call by day and by night and shudders with excitement at the premonition of that degree of happiness which eternities have prepared for those who will give thought to their true liberation. There is no way to help any soul attain this happiness, however, so long as it remains shackled with the chains of opinion and fear. And how hopeless and meaningless life can become without such a liberation! There is no drearier, sorrier creature in nature than the man who has evaded his own genius and who squints now towards the right, now towards the left, now backwards, now in any direction whatever.

Echoing Picasso’s proclamation that “to know what you’re going to draw, you have to begin drawing,” Nietzsche considers the only true antidote to this existential dreariness:

Echoing Picasso’s proclamation that “to know what you’re going to draw, you have to begin drawing,” Nietzsche considers the only true antidote to this existential dreariness:

No one can build you the bridge on which you, and only you, must cross the river of life. There may be countless trails and bridges and demigods who would gladly carry you across; but only at the price of pawning and forgoing yourself. There is one path in the world that none can walk but you. Where does it lead? Don’t ask, walk!

But this path to finding ourselves, Nietzsche is careful to point out, is no light stroll:

How can man know himself? It is a dark, mysterious business: if a hare has seven skins, a man may skin himself seventy times seven times without being able to say, “Now that is truly you; that is no longer your outside.” It is also an agonizing, hazardous undertaking thus to dig into oneself, to climb down toughly and directly into the tunnels of one’s being. How easy it is thereby to give oneself such injuries as no doctor can heal. Moreover, why should it even be necessary given that everything bears witness to our being — our friendships and animosities, our glances and handshakes, our memories and all that we forget, our books as well as our pens. For the most important inquiry, however, there is a method. Let the young soul survey its own life with a view of the following question: “What have you truly loved thus far? What has ever uplifted your soul, what has dominated and delighted it at the same time?” Assemble these revered objects in a row before you and perhaps they will reveal a law by their nature and their order: the fundamental law of your very self. Compare these objects, see how they complement, enlarge, outdo, transfigure one another; how they form a ladder on whose steps you have been climbing up to yourself so far; for your true self does not lie buried deep within you, but rather rises immeasurably high above you, or at least above what you commonly take to be your I.

With this, Nietzsche turns to the true role of education in the excavation of this true self — something Parker Palmer addressed a century later in his beautiful meditation on education as a spiritual journey — and writes:

Your true educators and cultivators will reveal to you the original sense and basic stuff of your being, something that is not ultimately amenable to education or cultivation by anyone else, but that is always difficult to access, something bound and immobilized; your educators cannot go beyond being your liberators. And that is the secret of all true culture: she does not present us with artificial limbs, wax-noses, bespectacled eyes — for such gifts leave us merely with a sham image of education. She is liberation instead, pulling weeds, removing rubble, chasing away the pests that would gnaw at the tender roots and shoots of the plant; she is an effusion of light and warmth, a tender trickle of nightly rain…

In a sentiment that calls to mind David Foster Wallace’s superb commencement address on the true value of education, Nietzsche concludes:

There may be other methods for finding oneself, for waking up to oneself out of the anesthesia in which we are commonly enshrouded as if in a gloomy cloud — but I know of none better than that of reflecting upon one’s educators and cultivators.

Complement the altogether fantastic Schopenhauer as Educator with Nietzsche on the power of music and his ten rules for writers, then revisit Florence King on how to find yourself and Parker Palmer on how to let your life speak.

______________________________

Brain Pickings is the brain child of Maria Popova, an interestingness hunter-gatherer and curious mind at large obsessed with combinatorial creativity who also writes for Wired UK and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow. She has gotten occasional help from a handful of guest contributors.

Go to Original – brainpickings.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.