Saudi Court Sentences Poet to Death for Renouncing Islam

MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA, 30 Nov 2015

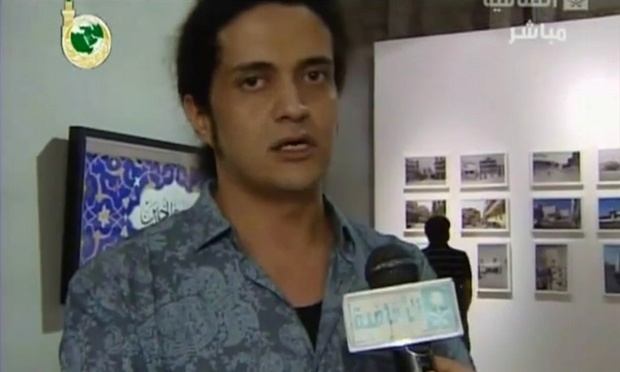

Friends of Palestinian Ashraf Fayadh believe he is being punished for posting video showing religious police lashing a man in public.

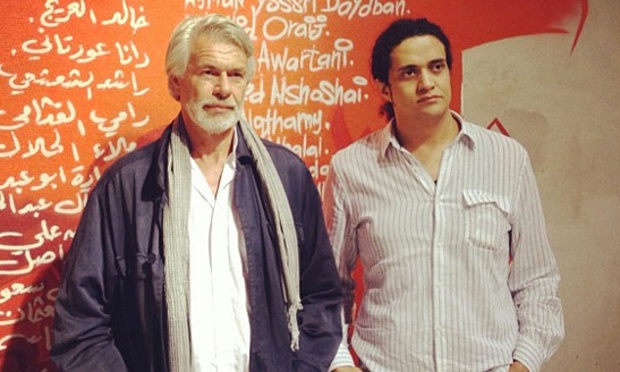

Ashraf Fayadh, right, with art historian Chris Dercon, outgoing director of Tate Modern, attend the opening of an exhibition in Jeddah curated by Ashraf Fayadh. Photograph: Ashraff Ayadh/Instagram

20 Nov 2015 – A Palestinian poet and leading member of Saudi Arabia’s nascent contemporary art scene has been sentenced to death for renouncing Islam.

A Saudi court on Tuesday ordered the execution of Ashraf Fayadh, who has curated art shows in Jeddah and at the Venice Biennale. The poet, who said he did not have legal representation, was given 30 days to appeal against the ruling.

Fayadh, 35, a key member of the British-Saudi art organisation Edge of Arabia, was originally sentenced to four years in prison and 800 lashes by the general court in Abha, a city in the south-west of the ultraconservative kingdom, in May 2014.

But after his appeal was dismissed he was retried earlier this month and a new panel of judges ruled that his repentance did not prevent his execution.

“I was really shocked but it was expected, though I didn’t do anything that deserves death,” Fayadh told the Guardian.

Mona Kareem, a migrant rights activist from Kuwait who has led a campaign for the poet’s release, said: “For one and a half years they promised him an appeal and kept intimidating him that there’s new evidence.

“He was unable to assign a lawyer because his ID was confiscated when he was arrested [in January 2014]. Then they said you must have a retrial and we’ll change the prosecutor and the judges. The new judge didn’t even talk to him, he just made the verdict.”

Fayadh’s supporters believe he is being punished by hardliners for posting a video online showing the religious police (mutaween) in Abha lashing a man in public. “Some Saudis think this was revenge by the morality police,” said Kareem.

Kareem also believes that Fayadh has been targeted because he is a Palestinian refugee, although he was born in Saudi Arabia.

The religious police first detained Fayadh in August 2013 after receiving a complaint that he was cursing against Allah and the prophet Muhammad, insulting Saudi Arabia and distributing a book of his poems that promoted atheism. Fayadh said the complaint arose from a personal dispute with another artist during a discussion about contemporary art in a cafe in Abha.

He was released on bail after one day but the police arrested him again on 1 January 2014, confiscating his ID and detaining him at a police station until he was transferred to the local prison 27 days later. According to Fayadh’s friends, when the police failed to prove that his poetry was atheist propaganda, they began berating him for smoking and having long hair.

“They accused me [of] atheism and spreading some destructive thoughts into society,” said Fayadh. He added that the book, Instructions Within, published in 2008, was “just about me being [a] Palestinian refugee … about cultural and philosophical issues. But the religious extremists explained it as destructive ideas against God.”

The case went to trial in February 2014 when the complainant and two members of the religious police told the court that Fayadh had publicly blasphemed, promoted atheism to young people and conducted illicit relationships with women and stored some of their photographs on his mobile phone.

Fayadh denied the accusations of blasphemy and told the court he was a faithful Muslim. According to the court documents, he said: “I am repentant to God most high and am innocent of what appeared in my book mentioned in this case.”

The documents also state that he admitted that he had relationships with the women. But Fayadh said his words had been twisted: the women were fellow artists and the photos on his phone, some of which he posted on Instagram, were taken during Jeddah art week, Saudi Arabia’s most important contemporary art event.

The case highlights the tensions between hardline religious conservatives and the small but growing number of artists and activists who are tentatively pushing the boundaries of freedom of speech in Saudi Arabia, where cinema is banned and there are no art schools. Abha, which has become a hub for contemporary Saudi art, has been a focal point for these disputes in recent years. An anonymous collective of film-makers who set up a secret cinema in the city in October 2012 received death threats from hardliners.

The kingdom’s best known contemporary artist, Ahmed Mater, who lives in Abha and testified in Fayadh’s defence at his first trial, said: “Ashraf is well known in Abha and the whole of Saudi Arabia. We are all praying for his release.”

Stephen Stapleton, co-founder of Edge of Arabia, said Fayadh had been a key figure taking Saudi contemporary art to a global audience.

“He was instrumental to introducing Saudi contemporary art to Britain and connecting Tate Modern to the emerging scene,” said Stapleton. “He curated a major show in Jeddah in 2013 and co-curated a show at the Venice Biennale later that year.

“I’ve known him since 2003. He’s a truly wonderful, kind person. He’s an intellectual and creative but he’s not an atheist.”

Adam Coogle, a Middle East researcher for Human Rights Watch, said Fayadh’s death sentence showed Saudi Arabia’s “complete intolerance of anyone who may not share government-mandated religious, political and social views”.

“The trial records in this case indicate clear due process violations, including charges that do not resemble recognisable crimes and lack of access to legal assistance,” he said.

“This case is yet another black mark on Saudi Arabia’s dismal human rights record in 2015, which includes the public flogging of liberal blogger Raif Badawi in January and a death sentence for Ali al-Nimr, a Saudi man accused of protest-related activities allegedly committed before he was 18 years old.

“If Saudi Arabia wishes to improve its human rights record it must release Fayadh and overhaul its justice system to prevent all prosecutions solely for peaceful speech – especially those that result in beheading.”

____________________________________

David Batty is a news editor and reporter. His specialist areas are visual art, higher education, the Middle East and social affairs. He has worked at the Guardian since 2001 and was previously a health correspondent.

Go to Original – theguardian.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA: