The New Gilded Age: Close to Half of All Super-PAC Money Comes from 50 Donors

ANGLO AMERICA, 25 Apr 2016

Matea Gold and Anu Narayanswamy – The Washington Post

15 Apr 2016 – A small core of super-rich individuals is responsible for the record sums cascading into the coffers of super PACs for the 2016 elections, a dynamic that harks back to the financing of presidential campaigns in the Gilded Age.

Close to half the money — 41 percent — raised by the groups by the end of February came from just 50 mega-donors and their relatives, according to a Washington Post analysis of federal campaign finance reports. Thirty-six of those are Republican supporters who have invested millions in trying to shape the GOP nomination contest — accounting for more than 70 percent of the money from the top 50.

San Francisco environmentalist and former hedge-fund manager Tom Steyer is the biggest super PAC donor of 2016. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

In all, donors this cycle have given more than $607 million to 2,300 super PACs, which can accept unlimited contributions from individuals and corporations. That means super PAC money is on track to surpass the $828 million that the Center for Responsive Politics found was raised by such groups for the 2012 elections.

The staggering amounts reflect how super PACs have become fundraising powerhouses just six years after they came on the scene. The concentration of fundraising power carries echoes of the end of the 19th century, when wealthy interests spent millions to help put former Ohio governor William McKinley in the White House.

[Meet the wealthy donors who are funneling millions into the 2016 elections]

Despite the mixed impact that big-money groups have had on the presidential contest so far, donors on both sides of the aisle are expected to shell out hundreds of millions more to such entities before the November elections.

“We’re going to save firepower for whoever the Republican nominee is,” said Dallas investor Doug Deason, whose father, billionaire technology entrepreneur Darwin Deason, is financing super PACs supporting Sen. Ted Cruz (Tex.).

Wealthy patrons also are turning their attention to congressional races. Already, more than two dozen super PACs each backing a single House or Senate candidate have emerged.

The biggest surge of cash is likely to come this fall, when millionaires and billionaires aligned with both parties fully engage in the fights for control of the White House and Congress.

“Democratic donors see Republican donors giving huge, seven-figure checks to causes and efforts on the Republican side of the aisle, and our donors don’t want to be silenced,” said Alixandria Lapp, executive director of the House Majority PAC, a Democratic group that has raised $10 million.

The biggest overall contributor to super PACs so far is San Francisco environmentalist and former hedge-fund manager Tom Steyer, who has put $17 million into a super PAC he formed to support candidates committed to combating climate change. He said last month that he plans to spend more than the $70 million he plowed into the group to support Democrats in the 2014 elections.

[Billionaire climate activist to spend big bucks this cycle, but he faces a problem]

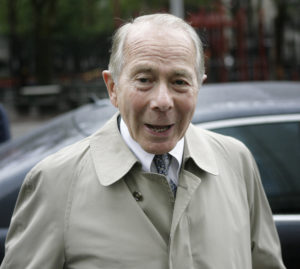

FILE – In this June 18, 2009 file photo, former American International Group (AIG) Inc. Chairman Maurice “Hank” Greenberg, the former head of insurance giant AIG, gave $15 million to super PACs backing Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio before they dropped out of the GOP presidential race. (Seth Wenig/AP)

Others are spreading around their wealth. New York hedge-fund billionaire Paul Singer gave $5 million to a super PAC allied with Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), whose White House bid fizzled, and nearly $5 million more to nine other super PACs, including one working to stop Republican front-runner Donald Trump.

Elite givers such as Steyer and Singer are increasingly driving the financial power of these groups. The Post found that the top 50 contributors together donated $248 million personally and through their privately held companies, or more than $4 out of every $10 raised by all super PACs.

To put that in perspective: This tiny cohort of mega-donors supplied more money than the combined contributions of nearly 1 million supporters of Democratic presidential front-runner Hillary Clinton, whose campaign raised $161 million in the same time period. Unlike super PACs, candidates cannot accept corporate money, and individual contributions to them are limited to $2,700 per election.

Echoes of the Gilded Age

Michael Malbin, executive director of the nonpartisan Campaign Finance Institute, said the last time political wealth was so concentrated was in 1896, when corporations and banking moguls helped McKinley, the Republican candidate, outspend Democratic rival William Jennings Bryan.

“The peak of the system for tapping corporations and rich people came in the McKinley campaign,” he said. “I think that would be an equivalent.”

Populist anger over how presidential races were financed led to a 1907 ban on corporations donating to federal campaigns. Forty years later, Congress prohibited unions and corporations from making independent expenditures in federal races.

The picture dramatically changed in 2010, when the Supreme Court said in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that corporations and unions could spend unlimited sums on politics as long as they did it independently of campaigns and parties. The decision paved the way for super PACs, which are now a norm in federal races.

This year, the groups are attracting supporters who have made fortunes in a variety of industries. Hedge-fund managers and energy tycoons figure prominently among the top 50 donors, as do technology executives and owners of professional sports teams.

[How much money is behind each campaign?]

Some of the biggest givers are return players from previous elections, such as conservative hedge-fund manager Robert Mercer, who has shelled out $14.6 million so far this cycle, largely to a super PAC backing Cruz. Liberal investor George Soros has given $8 million to support groups allied with Clinton and the Democrats.

But the ability to play at such a high level has also captivated a new class of political givers. Among the top donors are people who had not given substantial contributions to super PACs in past years, including fracking industry billionaires and brothers Farris and Dan Wilks, energy investor Toby Neugebauer, car-dealing magnate Norman Braman, and hedge-fund manager Steven Cohen and his wife, Alexandra.

Three hundred donors who have given at least $10,000 have invested in more than one super PAC, the Post analysis found. Among the most prolific is New York-based financier Roger Hertog, who backed super PACs aligned with most of the GOP presidential field. He doled out $510,000 to groups supporting Rubio, former New York governor George Pataki, former Louisiana governor Bobby Jindal, Sen. Lindsey O. Graham (S.C.), former Florida governor Jeb Bush and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, among others.

Ukrainian-born investor Leonard Blavatnik, who owns Warner Music Group, gave $3.35 million through his company Access Industries to four super PACs, including those supporting Graham, Rubio and Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker.

Large vs. small donors

Indeed, mega-donors seeking an alternative to Trump have exhausted millions of dollars of their personal wealth, raising questions about how effectively outside money can shape this presidential race.

Other than Trump, the most successful White House contenders of 2016 have been fueled by large bases of small donors — Cruz on the GOP side, and Clinton and Sen. Bernie Sanders (Vt.) for the Democrats. Sanders, in particular, has seen remarkable success, raising nearly $140 million, largely though small donations made online.

[Some Democrats accuse Sanders supporters of harassing delegates]

Some major donors said such vigorous grass-roots fundraising undercuts the idea that a few wealthy individuals are driving the action.

“To date, this may be the most democratic election in American history,” said Neugebauer, the Republican energy investor, who has given more than $10 million to super PACs aligned with Cruz. “The special interest large donors are being overpowered by the millions of Americans who want their country back.”

Still, rich supporters have funded an entire network of pro-Cruz super PACs, which have together spent nearly $40 million supporting his bid.

Many party strategists say the GOP presidential contest is an imperfect test of the power of super PACs because of the way Trump’s provocative candidacy has dominated the airwaves.

“I don’t believe that phenomenon is replicable in future cycles and certainly not in down-ballot races,” said Republican campaign lawyer Charlie Spies, who served as treasurer of the pro-Bush super PAC Right to Rise, which spent more than $100 million before Bush dropped out of the race. “So it is very hard to draw broad lessons from super PACs in this presidential election because of the overwhelming earned-media advantage Donald Trump has had.”

Some donors who have supplied big checks to unsuccessful super PACs are holding off from giving more. But others continue to invest in such groups.

“I haven’t seen any rate of diminishment,” said Brian Baker, a Republican strategist who advises the Ricketts family, which owns the Chicago Cubs and has donated $7 million to GOP-allied groups, including $5 million to an anti-Trump organization. “Campaigns need message and manpower. You need the money to fund those two things, and I think people fundamentally understand that.”

Al Hoffman Jr., a Florida developer and former ambassador to Portugal, said the $1 million he gave to Right to Rise “was worth every dollar,” adding that Bush “advocated ideas and policy, and he stuck to his guns.”

Hoffman, who does not plan to put more into the presidential race until the GOP nominee is selected, is now raising money for Brian Mast, a Republican running to replace Rep. Patrick Murphy (D-Fla.).

“I will probably give money to a super PAC for him,” he said.

__________________________________

Matea Gold is a national political reporter for The Washington Post, covering money and influence.

Go to Original – washingtonpost.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.