Popular Representation and Democracy in Syria – End of `Alawite Dictatorship’?

SYRIA IN CONTEXT, 2 May 2016

Kristian Girling – Oriental Review

27 Apr 2016 – The Syrian parliamentary election of 13 April 2016 is demonstrative of the apparent and continuing plurality of Syrian society as manifested within the People’s Council – a parliamentary body which has often been regarded as merely a façade of legitimation for the ruling Baath Party government of President Bashar al-Assad. Plurality within the parliament is of significance insofar as it is indicative of the involvement of a range of religious communities in Syrian political life and runs directly contrary to the prevailing narrative of Syria as a dictatorship dominated by the Alawite religious community, of which the Assad family are members, and to the exclusion of the involvement of other religious communities in political activity.

Elections to the 250 member Syrian People’s Council take place every four years with the country divided into fifteen multiple seat constituencies. Since 2012 and amendments to the country’s constitution Syrian political life has been, in theory, open to participation to a wider array of political parties than the Baath and other permitted parties such as the Syrian Social Nationalist or Syrian Communist parties. Previously the Syrian Baath Party had looked likely to retain power in parliament indefinitely and indeed to dominate either directly by its own MPs or indirectly via allied parties and MPs. However, with the changes there is limitation on presidential office to seven years for any one candidate, no president can rule for more than two seven year terms, the president can now be someone who is not a member of the ruling National Progressive Front coalition, and the constitution no longer has a stipulation that the Baath Party is to be the normative and leading influence in Syrian socio-political life. Such changes may seem relatively minor and indeed the Baath Party will likely remain the de facto power in Syria for some time to come but they are indicative of President Assad’s openness to pursuing gradual reform on a model which is perceived as suitable for Syrian circumstances.

Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad (C) casts his vote next to his wife Asma (centre left) inside a polling station during parliamentary elections in Damascus, Syria, on April 13, 2016.

A key aspect of encouraging and maintaining societal stability in Syria since independence from French rule in 1946 has been to ensure that authoritative political leadership is combined with some type of broad representation of the plural religious and ethnic communities resident to Syria and ensure that they have a stake in determining Syria’s development. An important issue has been to ensure that those outside of the Alawite community have opportunities to take on representative roles and to know their contributions to Syrian society are valued. Criticism has focused on the Alawite strength and/or prevalence to many spheres of Syrian life but especially economically and in the security services to the detriment of others. The People’s Council appears to an extent to undermine these critiques as exemplified by the majority of seats being held by Syrians of the majority Sunni Muslim community.

Alawites and plural representation in the People’s Council

The Alawite community broadly identifies itself as part of Shia Islam having emerged in the late ninth/early tenth centuries in western Syria possibly around the figure of the eleventh Shia Imam, Hasan al-Askari. To the external observer it might seem that the Alawites are more a syncretistic movement containing aspects of Christianity and Twelver Shia Islam given, amongst other activities, they celebrate a type of Divine Liturgy including the consecration of wine alongside strong reverence for Ali ibn Abi Talib, the son-in-law and cousin of the Islamic prophet, Mohammed. This combination of — or plurality of — beliefs in part explains why the Assad family has consistently supported the notion of a plural Syria and the general advancement of a paradigm of laïcité for the Syrian state and in which, in theory, no-one religion should predominate to the detriment of another.

The Alawites currently form around ten–fifteen percent of the Syrian population (c.2,000,000 people) and are concentrated in the western coastal provinces of Latakia and Tartus. During the French Mandate in Syria (1923–1946) the Alawites were often strong supporters of French administration as their rule was perceived as a means to secure the Alawite community in a society which was not necessarily comfortable with their presence. Although Alawites consider themselves to be part of the Islamic milieu some Muslims, especially within the Sunni community, do not and find such assertions religiously and politically challenging.

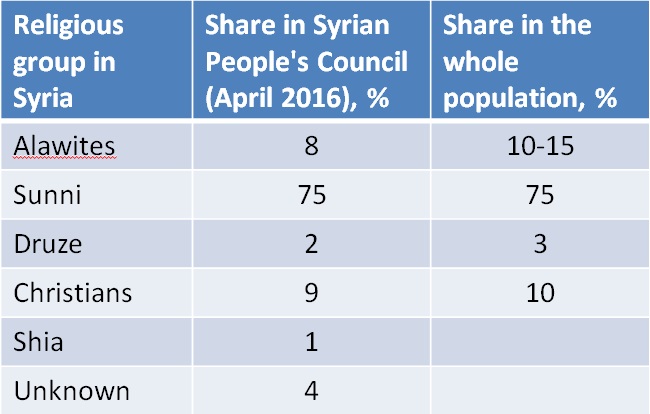

The Alawite influence in the Syrian ruling élite within post-independence Syrian political affairs arose in the early 1970s when Hafez al-Assad (Bashar’s father) came to power as President. In general terms Hafez organised the state such that Sunnis held élite political offices and the Alawites held responsibility for the security services. The perception of the Syrian Baath establishment as a bastion of Alawite and to a lesser extent Christian power has not consistently sat well with the Syrian Sunni majority and it has been suggested that, in reality, they have been denied the opportunity to take a full part in Syrian political life. However, as I have noted, the People’s Council is predominantly Sunni and representative on a proportional level to the extent of almost matching the religious demographics of Syria:

These figures for Syrian MPs by religion were the only available as of 27 April 2016. Please contact ORIENTAL REVIEW if you are aware of another breakdown of these demographics.

Such a balance is important as a means to legitimise the Syrian government’s claims to being the lawful and representative body controlling the Syrian state insofar as it can affirm it represents the interests of the full range of Syrian communities but also demonstrative of Sunni willingness to commit to the existing political establishment and loyalist campaign against Da’esh and other terrorist factions.

It should be noted that within the People’s Council there is a strong diversity of MPs and whilst as might be expected Latakia and Tartus are dominated by Alawite representatives there are also Christian and Sunni MPs in these regions. Moreover, women of Shia, Sunni, Alawite, Druze and Christian background also take a full part in Syrian political life with 29 female MPs (11 percent). Such a scenario were Da’esh to have successfully occupied Syria would, of course, be unthinkable.

Critiquing the Syrian elections

It appears that whether or not the April 2016 Syrian elections were actually entirely free and fair that it is enough for claims and accusations to be advanced to ensure they are characterised as a `sham’ and not reflecting the true results and popular will of the people. Such claims do not appear to more than scratch the surface of what actually took place beyond continuing to follow the set narrative of President Assad as a dictator only interested in advancing Alawite interests and the elections as likely fraudulent with only Baath loyalists actually gaining positions in reality.

This is not to suggest that Syria’s political process and elections are necessarily more than a very basic level of democratic participation. However, the elections did take place and furthermore, the current Syrian government may be many things but it appears, at the very least, to be gradually encouraging the transition to a more representative style of political system. It may not be one which external observers approve of, or, is the ideal of those external powers seeking violent and radical change for Syria but it is a process of political development which is taking place in the Syrian context and as far as the current lawful government is concerned, is perceived as the most likely method to manage Syrian plurality and to ensure some type of peaceful if long-term change in governance can take place with the minimum of extremist political forces further damaging the mosaic of Syrian society.

It is notable that Western states can be far less critical of other Middle Eastern powers with whom they are allied and who appear to have similar political structures to Syria or limited interest in widening political participation. The Kingdom of Bahrain, for example, is a Sunni led and dominated constitutional monarchy. The monarch in effect, however, is the final deciding authority in Bahrain and, for example, directly appoints the members of the Bahrani upper parliamentary house. Moreover, the majority Shia population (65–75 percent) of Bahrain has struggled to gain a strong and active voice in Bahrani socio-political life. This is not to single out Bahrain for criticism — indeed it has, like Syria, begun to transition to a more representative type of governance — but to be aware of the comparative type of narratives which are being pursued in the region with states such as Bahrain portrayed as reliable and honourable allies of the West but the Syrian government as beyond the pale for engagement by Western and Gulf states. Accusations of impropriety in democratic processes being one of the means to continue to critique the rule of President Assad.

We might also compare the democratic representation in Western states such as the United Kingdom, which have been consistently critical of the Syrian government since 2012, with attempts to proportionately represent Syrian communities in the People’s Council. We can note, for example, following the 2015 UK General Election that despite the UK Independence Party and Green Party receiving respectively c. 3,800,000 and 1,100,000 votes both parties have only one MP in the House of Commons. Whereas, the Scottish National Party received c. 1,400,000 votes and have fifty-six MPs. The peculiarities of the UK’s `First Past the Post’ electoral system are such that these results are valid returns, nonetheless, the external observer might ask are these results just, and, do they convey and strengthen confidence in the legitimate representative nature of British democracy?

Conclusion

The results of the 2016 Syrian elections are suggestive of the population’s commitment to the ideal of plurality in Syria through a popular willingness to take part in the elections and gain access to some type of political representation for all Syrians. We can note that a key aspect of critiquing President Assad’s leadership is the notion that he rules as a dictator and this because he favours one section of the population over others on a confessional basis. Notwithstanding that such critiques might be more vigorously and profitably pursued against other states in the Middle East it also speaks to a lack of comprehension as to how the realities of Syria’s plural society affect the type of government and form of rule which is maintained.

Syria under the Assad-Baathist governments cannot be said to hold to a representative system which is readily appreciated or supported by external observers who are used to models found in liberal democratic capitalist societies or that the Syrian system is indeed supported by the majority of the Syrian people. Nonetheless, it is a political system which has been sustained for over half a century. If the status quo in Syria has seen Alawite predominance, other confessions have not been consistently denied the opportunity to take a part in Syrian socio-economic and political life — without at least the acquiescence of the majority of the Syrian Sunni population to Assad-Baathist rule such a paradigm could not and would not have been sustained for so long.

If we are to speak of an Alawite dictatorship or Alawite over-dominance in recent Syrian history the most apparent example is in a “dictatorship of the dead”. A disproportionate burden of Syrian Arab Army casualties in the campaigns against Da’esh and its allies have been borne by the Alawite community with up to a third of Alawite young men having been killed in the conflict. It is possible that the Alawite sacrifices in this regard are such that other Syrian communities are recognizant of the commitment which the Alawites have to maintaining Syrian plurality and sustaining some form of societal stability and peaceful social interaction which has led to Sunni, Christian, Druze and Shia continuing to support President Assad’s government and willingness to engage with the gradually reforming political process.

________________________________

Kristian Girling is a freelance writer and a post-doctoral research fellow at Heythrop College, University of London.

Go to Original – orientalreview.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.