The Smoking Gun! No Question on Illegality of the U.S. Overthrow of the Hawaiian Government in 1893

ASIA--PACIFIC, 9 Jan 2017

Hawaiian Kingdom Blog – TRANSCEND Media Service

2 Jan 2017 – In 2016, Duke University Press published Tom Coffman’s Nation Within: The History of the American Occupation of Hawai‘i. While this book has been in circulation since 1998, it is the first time that an academic publisher has put its name to the book. The goal of Duke University Press is “to contribute boldly to the international community of scholarship.” “By insisting on thorough peer review procedures in combination with careful editorial judgment, the Press performs an intellectual gatekeeping function, ensuring that only scholarship of the highest quality receives the imprimatur of the University.”

Dr. Keanu Sai, a political scientist, whose doctoral research covered the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its continued existence today as an independent State, was asked by the Hawaiian Journal of History to write a book review of Coffman’s Nation Within for its first publication in 2017. In his review, Dr. Sai reveals the “smoking gun” that was brought to his attention by Dr. Ron Williams of the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa.

Dr. Keanu Sai, a political scientist, whose doctoral research covered the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its continued existence today as an independent State, was asked by the Hawaiian Journal of History to write a book review of Coffman’s Nation Within for its first publication in 2017. In his review, Dr. Sai reveals the “smoking gun” that was brought to his attention by Dr. Ron Williams of the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa.

************************

In Nation Within: The History of the American Occupation of Hawai‘i, Tom Coffman exhibits a radical shift by historians in interpreting political events post-1893. When Coffman first published his book in 1998, his title reflected a common misunderstanding of annexation. But in 2009, he revised the title by replacing the word Annexation with the word Occupation. Coffman admitted he made this change because of international law (p. xvi). By shifting the interpretive lens to international law, Coffman not only changed the view to occupation, but would also change the view of the government’s overthrow in 1893. While the book lacks any explanation of applicable international laws, he does an excellent job of providing an easy reading of facts for international law to interpret.

In international law, there is a fundamental rule that diplomats have a duty to not intervene in the internal affairs of the sovereign State they are accredited to. Every sovereign State has a right “to establish, alter, or abolish, its own municipal constitution [and] no foreign State can interfere with the exercise of this right” (Halleck’s International Law, 3rd ed., p. 94). For an ambassador, a violation of this rule would have grave consequences. An offended State could proceed “against an ambassador as a public enemy…if justice should be refused by his own sovereign” (Wheaton’s International Law, 8th ed., p. 301).

In international law, there is a fundamental rule that diplomats have a duty to not intervene in the internal affairs of the sovereign State they are accredited to. Every sovereign State has a right “to establish, alter, or abolish, its own municipal constitution [and] no foreign State can interfere with the exercise of this right” (Halleck’s International Law, 3rd ed., p. 94). For an ambassador, a violation of this rule would have grave consequences. An offended State could proceed “against an ambassador as a public enemy…if justice should be refused by his own sovereign” (Wheaton’s International Law, 8th ed., p. 301).

John Stevens, the American ambassador to the Hawaiian Kingdom arrived in the islands in the summer of 1889. As Coffman notes, Stevens was already fixated with annexation when he “wrote that the ‘golden hour’ for resolving the future status of Hawai‘i was at hand,” (p. 114) and began to collude with Lorrin Thurston (p. 116). Thurston was not an American citizen but rather a third-generation Hawaiian subject. Stevens’ opportunity to intervene and seek annexation would occur after Lili‘uokalani “attempted to promulgate a new constitution, [which] was the event Thurston and Stevens had been waiting for” (p. 120).

On January 16, Stevens orders the landing of U.S. troops and “tells Thurston that if the annexationists control three buildings—‘Iolani Palace, Ali‘iolani Hale, and the Archives—he will announce American recognition of the new government” (p. 121). The following day, “Stevens tells the queen’s cabinet that he will protect the annexationists if they are attacked or arrested by government police” (Ibid.). However, unbeknownst to Stevens, the insurgents only took over Ali‘iolani Hale, which housed “clerks of the Kingdom” (p. 125). One of the insurgents, Samuel Damon, knowing Stevens’ recognition was premature, sought to convince Lili‘uokalani that her resistance was futile because the United States had already recognized the new government, and that she should order Marshal Charles Wilson, head of the government police, to give up the police station. Wilson was planning an assault on the government building to apprehend the insurgents for treason in spite of the presence of U.S. troops.

On January 16, Stevens orders the landing of U.S. troops and “tells Thurston that if the annexationists control three buildings—‘Iolani Palace, Ali‘iolani Hale, and the Archives—he will announce American recognition of the new government” (p. 121). The following day, “Stevens tells the queen’s cabinet that he will protect the annexationists if they are attacked or arrested by government police” (Ibid.). However, unbeknownst to Stevens, the insurgents only took over Ali‘iolani Hale, which housed “clerks of the Kingdom” (p. 125). One of the insurgents, Samuel Damon, knowing Stevens’ recognition was premature, sought to convince Lili‘uokalani that her resistance was futile because the United States had already recognized the new government, and that she should order Marshal Charles Wilson, head of the government police, to give up the police station. Wilson was planning an assault on the government building to apprehend the insurgents for treason in spite of the presence of U.S. troops.

International law clearly interprets these events as intervention and Stevens to be a “public enemy” of the Hawaiian Kingdom. This was the same conclusion reached by President Grover Cleveland, whose investigation was an indictment of Stevens and the commander of the USS Boston, Captain Gilbert Wiltse. “The lawful Government of Hawai‘i was overthrown without the drawing of a sword or the firing of a shot,” Cleveland said, “by a process every step of which, it may be safely asserted, is directly traceable to and dependent for its success upon the agency of the United States acting through its diplomatic and naval representatives” (p. 144). Because of diplomatic immunity, the United States, as the sending State, would be obliged to prosecute Stevens and Wiltse for treason under American law.

On December 20, 1893, a resolution of the U.S. Senate called for a separate investigation to be conducted by the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. Chaired by Senator John Morgan, a vocal annexationist, the purpose of the Senate investigation was to repudiate Cleveland’s investigation and to vindicate Stevens and Wiltse of criminal liability. One week later, the Committee held its first day of hearings in Washington, DC. Stevens appeared before the Committee and fielded questions under oath on January 20, 1894. When asked by the Chairman if his recognition of the provisional government was for the “purpose of dethroning the Queen,” he responded, “Not the slightest—absolute noninterference was my purpose” (Report from the Committee on Foreign Relations— Appendix, p. 550).

After the hearings, two reports were submitted on February 26, 1894—a Committee Report and a Minority Report. The committee of eight senators was split down the middle, with Morgan giving the majority vote for the Committee Report. Half of the committee members did not believe Stevens’ testimony of his non-intervention. The Minority Report stated, “We can not concur…in so much of the foregoing report as exonerates the minister of the United States, Mr. Stevens, from active officious and unbecoming participation in the events which led to the revolution” (Ibid., p. xxxv).

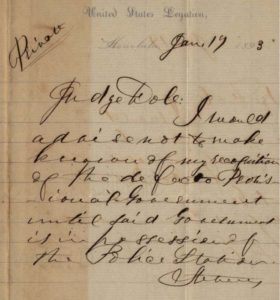

The Senate Committee’s investigation could find no direct evidence that would disprove Stevens’ sworn testimony, but in 2016, the “smoking gun” was found that would prove Stevens was a public enemy of the Hawaiian Kingdom, committed perjury before the Committee, and would no doubt have been prosecuted under the 1790 federal statute of treason. The Hawaiian Mission Houses Archives is processing a collection of documents given to them by a descendent of William O. Smith. Smith was an insurgent that served as the attorney general for Sanford Dole, so-called president of the provisional government.

The “smoking gun” is a note to Dole signed by Stevens marked “private” and written under the letterhead of the “United States Legation” in Honolulu and dated January 17, 1893. Stevens writes, “Judge Dole: I would advise not to make known of my recognition of the de facto Provisional Government until said Government is in possession of the police station.”

As a political scientist, Coffman’s book is a welcomed addition to arresting revisionist history.

_______________________________________

_______________________________________

Hawaiian Kingdom Blog – Weblog of the acting government of the Hawaiian Kingdom presently operating within the occupied State of the Hawaiian Islands.

Go to Original – hawaiiankingdom.org

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.