The Role of Biodiversity Scientists in a Troubled World

ANALYSIS, 6 Mar 2017

Abstract

Biotic resources are under all kinds of old and new threats. Ecosystem transformation in many areas of high biodiversity has not diminished, in spite of national and international meetings, agreements, and discussions. The main reasons to protect these resources are that little information is available on those we know exist and that the great majority of resources are yet to be discovered. One argument used to convince the general public and governments of the need to preserve biological resources is that there are many potential uses of unknown plants, animals, or micro organisms: New medicines, foods, chemicals, and genes are there to be discovered. Unfortunately, this argument has been overused and, as a result, has created unrealistic expectations of great riches and spurred stringent legal measures to restrict biodiversity research. The limits placed on biodiversity research and on access to biological resources are becoming a major obstacle to scientific discovery. Major projects have been suspended following unjustified criticisms. In this article, I discuss possible explanations for this problem and present some possible solutions.

*********************

We are living in troubled times. As a society, we are torn apart by conflicting views on issues of enormous importance. In the debate on many of these issues, both sides have persuasive arguments for their position. I hear convincing views from opposite extremes: pro-war or antiwar, pro-Israeli or pro-Palestinian, pro-GMO (genetically modified organism) or anti-GMO, pro-life or pro-choice, pro-bioprospecting or anti-bioprospecting. My colleagues send me all kinds of initiatives, asking me to sign petitions and protests about one issue or another. Sometimes it is easy to say yes, but sometimes not. I feel the anguish of having to take sides on issues I do not know well and whose reconciliation seems impossible.

Some of my colleagues also tell me that I should make up my mind and resolve the contradictions in my own views about conservation. These contradictions come from two apparently conflicting emphases in my past research. On one hand, I have been recognized as a pioneer in alerting the world about a possible major extinction episode that threatens the wet tropics because of their unique system of regeneration and the frightening scale of their ongoing deforestation (Gómez-Pompa et al. 1972). On the other hand, I am also recognized as a supporter of the new paradigm in conservation that includes indigenous societies of the past and present as key factors in conservation and in shaping the vegetation we wish to protect today (Gómez-Pompa and Kaus 1992). My more traditional conservation-minded colleagues regard with horror my defense of local indigenous practices as fundamental components of biodiversity management and conservation. How can I defend shifting agriculture, they ask, if it is almost universally considered a major cause of deforestation? Some of my more human-oriented colleagues regard with equal horror my defense of increasing the number of protected areas and strengthening global biodiversity research and conservation capacity.

In this article, I present my views on a related issue that is becoming highly polarized and about which I am also torn apart: the question of access to biological materials. This may also seem to be a hopeless controversy in which both sides have strong arguments for their position. However, it seems to me that by discussing its different sides, scientists may be able to do something to help solve or at least understand the problem.

The urgent need to protect and study tropical biodiversity is widely known. Scientists from all over the world have identified the need to intensify field studies in tropical biodiversity and to make its protection a high priority for this century (Raven 2000). We all are aware of the urgency of carrying out biodiversity studies in areas of rapid transformation. Yet, in addition to confronting the frightening deforestation rate that is occurring in areas known for their biodiversity (Myers 1995), researchers have been confronting major problems in undertaking urgently needed fieldwork. Available funds for fieldwork in the tropics are scarce, and the safety and health issues involved in traveling to remote places are important factors that any biodiversity scientist who wants to do field research has to consider.

In spite of all these challenges, many new students from developed and developing countries are entering fields related to tropical biodiversity and ethnobiology, which will require intensive fieldwork. These new scientists are confronting another obstacle that has been growing at an alarming rate: the new legal restrictions on field biodiversity studies that many countries are beginning to enforce. Alejandro Grajal (1999) called attention to this issue: “The development of cumbersome, erratic, and less transparent permit processes can produce a chilling effect on the collection, inventory, research, and monitoring of biodiversity just when the information is most needed.” This problem has been a standing worry to field biologists for many years.

In the past, one solution has been to ignore the restrictions and work in collaboration with scientists from well-known local academic institutions to avoid bureaucratic regulations. Until recently, it was understood that these regulations were meant for commercial collectors. This was an effective solution that helped many scientists make their important contributions without going through unnecessary paperwork. In my early life in Mexico, I was able to help local and foreign scientists with letters of introduction from the institutions to which I belonged (a condition being that they would include Mexican scientists and students in their fieldwork). There was an unwritten understanding with the authorities that this procedure was satisfactory. It was clear to all of us working in research that the principal target of these regulations was stopping the illegal collection of plants and animals to be sold mainly in Japan, the United States, and Europe. They were never intended to stop the flow of specimens and information on flora and fauna used for research purposes. However, not all scientists have been equally scrupulous about including local researchers in their work. There has always been resentment among many of my colleagues in Latin America about relaxed compliance with the law by many foreign scientists who never contacted local institutions, sought collaboration, or shared their results.

In recent times, a newer trend toward enforcement of regulations has emerged—probably caused by a misreading of articles 12 and 15 of the World Convention on Biodiversity (UNEP 1992). Article 12 reads, “Establish and maintain programs for scientific and technical education and training in measures for the identification, conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity and its components and provide support for such education and training for the specific needs of developing countries.” This article establishes the importance of promoting scientific education in biological diversity, not restricting research. In contrast, article 15 reads, “Recognizing the sovereign rights of States over their natural resources, the authority to determine access to genetic resources [genetic material of actual or potential value] rests with the national governments and is subject to national legislation.” Article 15, which was fueled by tremendous economic expectations on the part of developing countries and by mistrust directed against some hard-core conservationists (Macilwain 1998), opened the door to restricting access to biological resources.

The failure to distinguish clearly between access to biological samples for biodiversity research and access to genetic resources is having an impact on future research. Much-needed research on biodiversity is encountering major obstacles because of newly enforced, complex rules, laws, and regulations. These regulations not only restrict foreigners undertaking field research on tropical biodiversity but also affect the research of local scientists working in systematics, ecology, conservation biology, evolutionary biology, and ethnobiology. The arguments that are used to restrict access to genetic resources are meant to protect the biological heritage of nation-states from exploitation for economic benefit by outsiders. However, the restrictions also apply to insiders.

Some questions remain. Who should be responsible for doing research on genetic resources and on biodiversity? Since most biodiversity is unknown, should we treat all unknown taxa as potential genetic resources? Or should we consider as potential resources only close relatives of known genetic resources? These are important questions that require answers. The great paradox of this situation is that in the last few years, since these restrictions have been enforced, the tropical world has been subjected to probably the worst deforestation in history (Laurance 1999), because of forest clearing for cattle ranching and agriculture (Walker et al. 2000). In addition, forest concessions of millions of hectares in high-biodiversity areas have been given to local and international companies (Laurance 2000). These companies are not faced with major problems because of their destruction of genetic resources; unlike scientists, they do not need a collecting permit. Millions of hectares of mature tropical ecosystems are being transformed by agricultural expansion, cattle ranching, wood production, infrastructure development, and many direct and indirect impacts of poverty (Tole 1998). In spite of the well-intentioned efforts of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES 1973), the illicit trade of birds, butterflies, orchids, cacti, and cycads has not ended. It is clear that bureaucratic restrictions on scientific collections are not the answer for protecting the world’s biological heritage.

The future of biodiversity studies is at a crossroads. It is time for scientists and lawmakers to review the actions we have taken to know and protect the biodiversity of the world, and time to strengthen those measures that have worked and modify those that have not. Should we continue the trend of restrictions and destruction? Or should we go forward and find ways to eliminate these obstacles, looking for the necessary funds—which we all know exist in the developed world—to invest in training the cadres of scientists from all over the world to describe, study, and protect the biodiversity of the globe (Wilson 2000)?

In today’s global political environment, free trade, economic gain, and economic globalization at all costs are the name of the game (Stiglitz 2002). Almost anyone can have access to bulldozers and chemicals to transform the natural environment, and the resulting transformation creates little public outcry. Where are the protectors of genetic resources who designed the regulations inspired by the Convention on Biological Diversity? What have been the actions of signatory parties of the convention to stop this trend of biological destruction and impoverishment?

Even as biological devastation occurs unchecked throughout the world, biodiversity scientists who are willing to risk their lives to collect rare or unknown taxa for scientific purposes—entering guerrilla-inhabited areas, coca plantations, malaria-infested locations, or areas in the process of deforestation by forest exploitation—can experience months of waiting as they try to obtain official collecting permits. To obtain the permits, they may have to accept nonsensical requests, such as determining the number of new species that they expect to find and the number of specimens that they will be collecting. They may have to prepare quarterly reports of the fieldwork in process. The most frustrating part of this process is the lack of precise information on the application requirements and on the time needed to obtain a permit.

This problem is not unique to developing countries. In the United States, scientists complain about their inability to undertake important biodiversity research. In areas that are or will be protected because of species of concern, restrictions resulting from written and unwritten rules have resulted in the loss of existing permits or the refusal to issue new ones. Restrictions often change on a monthly or daily basis, preventing valuable information from being gathered. In most cases, permits are required for each individual administrative unit (state, county, and agency). These units include each national forest, Bureau of Land Management property, national park, county park, and so on. No scientist can be expected to predict an unusual event that will trigger an important biological process, and thus to request all the necessary permits beforehand. In many cases, important new findings are being lost because of the regulations that frustrate some of our most renowned scientists.

In most cases, scientists must pay fees to be allowed to do research and make collections. I believe that this is another unnecessary obstacle to scientific discovery. Scientists should not pay fees for doing research that is of general interest and benefit to all. Instead, they should be allowed to use these resources in exchange for accepting students and collaborating with local scientists. I am sure that most visiting scientists are willing to do this.

I understand the deep inequalities between developed and developing countries in terms of their scientific infrastructure, which may motivate these fees in the developing world. Yet often the government officials who promote such fees fail to recognize the need to conduct biodiversity research and to involve local scientists and students: Pay a fee, they seem to say, and you need do no more. Showing little concern for the safety of scientists or the importance of the research, they focus instead on the fear that biological riches will be stolen without compensation.

Some historical examples, such as Hevea from Brazil and Cinchona from Ecuador, have been used again and again to justify these regulations. There is a widespread myth that if the seeds of these trees had not left the countries of origin, the wealth produced by their discovery could have benefited the people there. Unfortunately, the history of introduction, cultivation, and domestication of trees does not support this myth. There are many variables that need to be considered to successfully introduce a new crop into cultivation. We should remember the case of coffee, which came from the mountains of Ethiopia and was introduced to Asia and America, and that of cacao, which was introduced from Mesoamerica to South America and Africa. Generally, crops do best when they are grown far from their place of origin, in places where they can escape (at least for a while) their biotic enemies.

It has been difficult in the past, and is even more so in the present, to enforce an embargo on transporting biological materials for commercial purposes from any country. One modern example was the unsuccessful case of the nationalization and embargo on trade of all species of the steroid-yielding Mexican yams (Dioscorea spp.) in the 1980s (Gómez-Pompa 1986, Soto-Laveaga 2001). It took only a few years before plantations of Mexican yams (Dioscorea composita, Dioscorea floribunda, and Dioscorea spiculiflora) began to appear in many tropical countries. Substitutes for Mexican yams were found in other species of Dioscorea and in several genera of Agavaceae, Leguminosae, Zingiberaceae, and Solanaceae (Samuelsson 1992). A few companies that were working in Mexico manufacturing steroids moved their operations to other countries, but the steroid industry continued as ever. The big losers were Mexico and the people supported by the industry in that country. The lesson learned from this failure seems to have been forgotten, namely that to control the trade of wild plants by requiring permits is a lost cause. The transgenic corn found in Oaxaca is just another example of how difficult it is to control or even track the movement of plants.

In spite of laws and regulations, the illegal trade of thousands of tons of plants and animals occurs every year. The idea that it is possible to stop the trade and movement of genes, plants, animals, and microorganisms by restricting the scientific community’s access to biological resources is not only naEFve but extremely shortsighted. Marijuana, a highly forbidden plant, is illegally produced and exported all over the world. In 2002, the Office of Drug Control Policy of the executive branch of the US government (White House 2003) listed $11.5 billion in federal funds as having been spent for drug control, which has not yet been successful in stopping the drug traffic into the United States.

Even as they deal with permit applications and regulations, biodiversity scientists and ethnobiologists doing research on medicinal and agricultural plants have been experiencing new and very harsh criticisms from several quarters. They have been confronted by aggressive national and international organizations that have accused them of stealing biological resources and indigenous knowledge and of violating indigenous intellectual property rights.

Is there any truth to these accusations? It is not easy to answer this question. Several projects (also called bioprospecting projects) have the objective of exploring wild biota for commercially valuable genetic and biochemical resources. These projects have been the principal target of the accusations of exploitation. One such project in Chiapas was headed by Brent Berlin, an outstanding ethnobotanist. After more than 30 years of work in the highlands of Chiapas, Berlin decided to undertake an impeccable bioprospecting project by engaging the collaboration of local scientists and indigenous communities. Unfortunately, this project was cancelled after a strong campaign of criticism by a local organization with the support of Rural Advancement Foundation International (now known as ETC, or Action Group on Erosion, Technology and Concentration), a very aggressive Canadian nongovernmental organization (NGO) dedicated to defending the intellectual property rights of rural communities.

For the project’s critics, the place and time for a major confrontation could not have been better. Chiapas is home to the well-known Zapatista guerrilla movement, which has declared war against the Mexican government and is asking for a major change in government policies toward indigenous communities. The Zapatistas’ fight for indigenous rights is widely supported by the Mexican people and by many groups outside Mexico. In this context, Berlin’s multimillion-dollar grant from the International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups was seen with distrust. In addition, the jealousy of nonparticipating groups, greed, and local politics in Chiapas have been major contributors to the polarized positions on this study. The academic community was behind Berlin, who has 30 years of brilliant studies on Highland Maya ethnobotany to his credit, but this support did not prevent the project’s cancellation. This has been a sad story that I hope will not be repeated (Dalton 2000). Unfortunately, several similar projects have been cancelled for similar reasons without such publicity (Cevallos 2000, Powledge 2001).

For many people in developing nations, the word “bioprospecting” brings up the distorted image of major corporations benefiting from local resources and local knowledge at no cost. Even biodiversity scientists who are not linked with bioprospecting projects are becoming innocent victims of a long history of mistrust toward projects coming from the developed into the developing world. This perception is clearly linked to the historic animosity toward some national or multinational corporations that have bad reputations because of their lack of concern for human misery and their overexploitation of natural resources. However, biodiversity scientists who are not working in applied projects are an inappropriate target for that resentment. Unfortunately, these scientists are the weakest link to the industrial world, easily attacked in place of other, more appropriate targets for criticism. In addition, their basic research can easily be confused with applied research for commercial or industrial purposes, particularly when the organisms they collect may have some practical application. Many times in the past, I have been asked by local people watching me press specimens, “Are these plants good for something?” My answer is always the same: “Of course—they are good for something that I don’t know, and that is why I study them.” I usually ask those people to tell me if they know what the plant is good for, and usually I get a good number of uses.

Local knowledge about useful plants is an important subject of research by ethnobotanists. There is a major discussion today on the need to recognize and compensate people who have shared their knowledge in projects that aim to search for new products. This idea appears to be fair, and we all agree that something should be done; however, there are many problems involved. Who are the owners of the knowledge—those who work directly with the researchers, or those from the community? What is a community? Should researchers create expectations by setting an agreement for compensation, knowing that the probabilities of a profitable discovery are very small and that, even in the event of such a discovery, it will be rewarded only on a long-term basis? How can we distinguish common knowledge? Each of these questions has many answers. Each answer will satisfy a few people but may not satisfy many. There are no written rules, and each case has to be dealt with sensibly, fairly, and with professional ethics.

For some reason, the political and scientific communities are ignoring the fact that efforts to compile information on useful plants have been an integral part of human history. Our botanical knowledge is accumulated from more than 300,000 years of human search for foods and medicines in nature. What many ethnobotanists are doing today follows the steps of Sumerian scientists, who more than 4000 years ago produced a series of clay tablets containing the first description of 250 drugs from plants (Cowen and Helfand 1990), or the steps of two notable Aztecs, MartEDn de la Cruz and Juan Badiano, who described the medicinal plants of their culture in 1552 (Emmart 1940). Today, the work of these ancient botanists is followed by that of thousands of scientists doing the same thing: publishing studies on useful plants.

The extinction of knowledge is as important as biological extinction (Cox 1999). According to Krauss (1992), more than 50 percent of the world’s languages have disappeared in the last century, and 90 percent of the remaining languages will either die or become moribund in this century. This is a major problem that should concern the whole world, and ethnobotanists in particular. Humans throughout history have produced masterfully written pieces of botanical knowledge. This knowledge of useful plants has traditionally been common knowledge, and we should make every effort for it to remain so.

There are hundreds of published articles and books on the medicinal plants of Mexico. Who is the owner of this knowledge? In recent times, the National Indigenous Institute of Mexico published an atlas of medicinal plants of Mexico (Argueta and Cano-Asseleih 1994). This information is a compilation of traditional knowledge that needs to be studied. No one is asking for the rights to use that knowledge, nor should they have to. As with any other scientific activity, the objective of publication is to provide information to others for evaluation and veri fication. Claims of property rights to common knowledge are absurd.

Biodiversity nationalism— extreme devotion to the defense of a country’s biodiversity against foreign interests—is becoming a distraction from the fundamental problems of inequality, poverty, corruption, social injustice, and colonialism that are pervasive in our world. Why do we accept all of this nonsense? Why have we reached this level of cynicism, impotence, and ignorance? Do scientists from industrialized nations feel guilty and hence inclined to accept a punishment, regardless of its injustice?

The attitude of most scientists working in the tropics (including myself) has been to accept this trend as something that is here to stay and to believe that there is nothing we can do about it. To openly criticize the laws and regulations of certain countries could endanger our activities in those countries. To openly criticize corporations and colleagues for their unethical behavior would not be very popular. However, to continue doing things as usual may not be the best strategy.

We should be proud of the great advances brought by scientific research in health, agriculture, and the environment. Scientific research has provided great opportunities to improve the quality of life for all humankind. No one questions the fact that most people in industrialized societies today live longer and enjoy better health than our ancestors. Unfortunately, these great advances are not generalized, as there are major sectors of the world and of our own industrial society that have not benefited fairly from them. Eighty percent of the people on our planet live in developing countries, where 80 percent of Earth’s biodiversity is found (Raven 2000), and the majority of the world’s population enjoys only a small percentage of its resources.

The processes of economic and informational globalization that characterize our times are affecting all human societies in many different ways. Information flows to the most remote places we can imagine. Many illiterate, primitive societies have access to news and information through television and radio. The globalization of information is real. However, the messages it conveys can produce misunderstandings, wrong expectations, and false visions of the world.

One important, successful message—which I believe is at the bottom of our problem—is the need to preserve the flora and fauna of the tropics. The importance of tropical biodiversity conservation has been the most important environmental message of all time. It has reached people everywhere, triggering numerous important activities at the global and national levels. Unfortunately, this message is usually accompanied by incomplete or overstated, though compelling, reasons for its importance. To biologists, the reason is simple and obvious: We are losing biological entities—from species to populations—at an unacceptable rate, because of human actions. However, to sell this message, we have had to give reasons that anyone can understand. One such reason is the untapped potential for new medicines. Scientists may have been successful in conveying this message, but not in fulfilling its promise of new products. If major medical discoveries from tropical resources do come in the future, they will come only in limi ted numbers.

Gene patenting of land races of agricultural crops, and the intellectual property rights associated with these plants, are even more complex topics that are generating misunderstandings and mistrust in many quarters. The simplistic approach of turning public goods (biological diversity) into private property may not be the best way to resolve the problems of equity and conservation; in fact, it could result in greater poverty and exploitation (Brush 1996, Stiglitz 2002). Here, again, we should be careful not to create false expectations in our honest efforts to convince authorities to take action to conserve biodiversity. One reason scientists often give to increase the number and size of protected areas of the world is the importance of keeping the biodiversity they contain for the future: New medicines may not be discovered, or extinctions may happen, if no actions are taken to preserve species and their habitat. But many people (usually in very poor indigenous communities) have been affected by the creation of these protected areas. They have been resettled or displaced or have had restrictions placed on the use of the resources on their own lands. Local people learn from rumor and the media of the wonders of new discoveries. Unfortunately, they don’t receive the benefits. As a result, a lot of resentment has been building up. The Zapatista revolt in Chiapas began with angry people who were displaced and mistreated when they were expelled from their homelands because of the establishment of a protected area. These are the same people whom ethnobotanists today want to study because of their impressive knowledge of nature. They are the ones for whom the advocates for indigenous intellectual property rights are requesting recognition.

Conservation organizations have made efforts to com pensate local people who are affected by the conservation actions of the so-called Integrated Conservation and Develop ment Projects (ICDPs) (Kremen et al. 1994). These efforts have been criticized as “conservation by distraction” (Ferraro and Kiss 2002). The promised benefits usually never materialize, and those that do are usually short-term, questionable “sustainable development” projects that produce a few good jobs for consultants and officers and temporary jobs for a limited number of local people. These unethical, short-term “fixes” are creating additional problems and, again, more resentment by local people against the entire subject of biodiversity conservation. A review of ICDPs in Indonesia by the World Bank found a notable lack of successful and convincing cases.

In one interesting development, scientists from the Smithsonian Institution have been teaching companies and consumers about the importance of shaded coffee and cacao plantations as agroforestry systems that favor biodiversity (Rice et al. 1997). If consumers are willing to pay a higher price for shade-grown coffee and cacao products, and if buyers are willing to share this benefit with the producers, this finding has the potential to have a great impact on biodiversity conservation and to improve the lives of millions of small farmers. However, this great initiative has been obscured by the increased production of cheap, poor-quality sun-grown coffee promoted by the four major international coffee buyers: Nestlé, Sara Lee, Procter and Gamble, and Kraft (Seno 2002). This overproduction has lowered world coffee prices to such a level that thousands of small coffee farmers in Mexico are going bankrupt and abandoning their plantations to find work elsewhere. Strangely enough, coffee prices for the consumer have not dropped.

The recent boom in the use of herbal remedies in the United States has also confused the perception of biodiversity research in developing countries. People do not necessarily know the difference between herbal and pharmaceutical medicines. Looking at the trade in herbal supplements, they see a multimillion-dollar industry based on plants. It is not surprising that local people in the tropics, who have long been users of this alternative medicine, question any project related to plants—specifically to medicinal plants—and suspect motives of economic exploitation.

Why should we insist on doing this type of research, when it involves so many obstacles? One reason is that time is running out: Not only are bodies of knowledge becoming extinct, organisms are as well. It is well accepted that the unprecedented extension, intensity, and kinds of disturbances that are occurring in the tropics threaten many species and all kinds of populations with extinction (Hughes et al. 2000). To understand and preserve the species that remain, we need to accelerate our studies on the biodiversity that exists today, performing more field research and looking for better ways to protect nature and local cultures. We need to understand all dimensions of the problems we are facing. There are no easy solutions. What can we do, considering the complexity of the challenges?

A major change in the way we treat our planet is in order. The 100 biggest economic entities (only half are nation-states) have a major responsibility for the state of the world (UNCTAD 2002). In addition, some developing nations need to change their antidemocratic, genocidal, and corrupt paths. We need to find ways to reduce or exchange the obscene debt many underdeveloped countries have, which is dramatically affecting the poorer people of these countries. An exchange of debt for a poverty alleviation program may be in order. Scientists and consumers need to convince multinational corporations to participate in a major way in programs of conservation and research on biodiversity, and also in educational programs that can help alleviate poverty in the countries where they do business.

We are all in the same boat. The principle of lifeboat ethics (Hardin 1974), whereby developed nations can ignore those who are drowning and who want to jump into their boat, is not going to work. If we do nothing, we will have to keep confronting angry people who are innocent victims of the inequalities, ignorance, and injustices of our world.

However, in the little part of the world where we may have an influence, there are things that we can do. We can help build or support local, national, and regional research capacities in the areas where we work. We can accept that the future of biodiversity research should be in the hands of local scientists working in collaboration with specialists from all over the world. A strong international scientific society working on biodiversity issues is the best weapon against unnecessary research impediments. We can find ways to fund the training of bright students in their own countries or abroad, creating educational opportunities for young people from traditional, indigenous communities to become teachers and researchers in their own culture. Corporations should be willing to help with this project. Can you imagine the impact of a fellowship fund created from as little as 0.1 percent of all the sales of food, seeds, and drugs derived directly or indirectly from wild sources?

Up to this point, I have tried to describe the many problems involved in access to biological resources and the difficulty in finding a solution. It is not easy to fix blame. Who is responsible: The communities who accuse scientists of biopiracy? The NGOs that make their living by questioning biodiversity projects? The pharmaceutical companies that search for new medicines from the wild? The legislators who restrict research? The scientists who ignore the laws of the countries in which they work? The projects that ignore the rights of indigenous people? The corporations that behave irresponsibly toward the environment and toward the impoverished communities in the countries where they do business?

It seems to me that all of these players have their share of responsibility. The solution is that each should take its own responsibility and act accordingly. I agree with Wendell Berry (1990), who wrote, “ The great obstacle is simply this: the conviction that we cannot change because we are dependent on what is wrong. But that is the addict’s excuse, and we know it will not do” (p. 201). There is no alternative. As scientists and citizens, we have to act locally in our own sphere of influence and try to bring about changes for the benefit of the many.

In the final part of this article, I will describe briefly two proj ects in which I am involved that deal with the topics I have been discussing: biodiversity research and ethnobotany. In the last 10 years, I have been involved in an international, interdisciplinary, and interinstitutional effort to study the ecological history and biodiversity of the lowland Maya region, using one previously unexplored site, El Eden Ecological Reserve, as a focal starting point (Gómez-Pompa et al. 2003). The idea of this study was to create a nongovernmental ecological reserve, dedicated to research and education in biodiversity conservation and management, that could be used as a reference site to reconstruct the ecological history of this region. I invited several students and colleagues to work together toward the goal of understanding a region that had been under disturbance for more than 3000 years. Our first project was a biodiversity assessment of this private reserve. The work done in the region so far includes biodiversity assessment of several groups of plants, animals, and microorganisms, in addition to archeological surveys, ecological studies, restoration ecology experiments, and a chemical ecology study on the alle lopathic potential of plants and fungi. A possible new biofertilizer, which was available to the ancient Maya, is under study, as well as a newly discovered system of wetland management. Advances in these findings, which all come from our small research site, are published in a multiauthor book (Gómez-Pompa et al. 2003).

One example of the work done at El Eden is the inventory of slime molds (Myxomycetes) performed by Stephenson and colleagues (2003). In this one reserve, they found one-third of the slime molds known to Mexico (table 1). Does this mean that El Eden has some unique quality that favors slime molds? Not at all. Rather, the explanation is simply that this is the only place in Mexico where these organisms have been studied in any depth. The same is true of several other groups of organisms under study.

The support for research and education in El Eden comes through individual grants obtained by participants and through contributions from the reserve’s founders, friends, and organizational and institutional donors. One important result from this endeavor has been the professional research conducted at the reserve. Even more important is the work of students. More than 15 theses have been researched at El Eden, and more are under way.

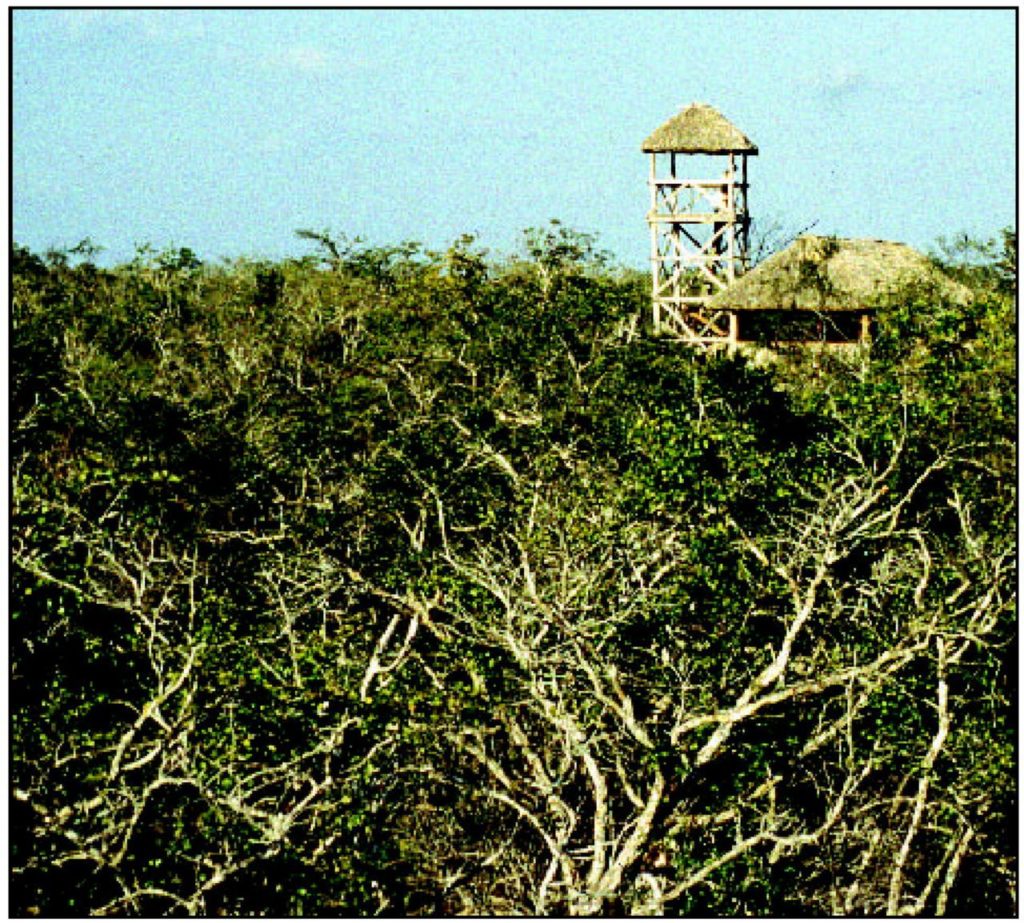

The rustic but comfortable facilities deep in the forest (figure 1) have attracted people who would like to copy our setting in other places, creating similar reserves and opening them up for research and ecotourism. We have invited people from local communities in Quintana Roo to learn about our project and visit our facilities, with the possibility of working with us to open similar sites in their communities. We are working with the newly established Center for Tropical Studies of the University of Veracruz (Centro de Investigaciones Tropicales, or CITRO), in collaboration with local communities, to facilitate the creation of a network of nongovernmental protected areas, similar to El Eden Reserve, in important sites.

Are we going to have problems? Maybe. But we feel that we have to test an alternative model that can respond to the needs of the scientific community and the interests of local people and, we hope, gain the approval of government offices. This project has the great advantage of being an initiative of the owners of the land and will be run by local scientists and other community members.

There is a strong movement in Mexico to create a network of nongovernmental protected areas for conservation, ecotourism, and scientific research. The successful experience in Costa Rica has had a great influence on this movement, which is spreading quickly in Latin America. Support from the international community for this effort could be of enormous value to promote badly needed, truly collaborative research with our colleagues in Latin America.

Like many other scientific endeavors in the developing world, ethnobotanical research is under scrutiny. It seems to me that we, the researchers in this field, have failed to communicate the importance, approaches, and objectives of ethno botanical research to the public and to our colleagues in other disciplines. The shopping list of plant names and uses is no longer the principal thrust of ethnobotanical research; neither is the search for new products. Instead, the study of human–plant relationships is providing challenging scientific insights into the process of generation of knowledge by folk science and into the different ways in which human societies have improved and managed their biotic resources and their environment. To develop this understanding further, we need to train a new generation of ethnobotanists from developing countries in hypothesis-based ethnobotanical research. These local researchers should be the principal scientists to capture, analyze, and evaluate traditional knowledge on plants and environment.

There are many misconceptions about the discipline of ethno botany. Scientists in this field are making the same mistake we did with biodiversity: creating exaggerated expectations of great discoveries of economic importance from local uses of plants. Even though we may wish these expectations could be fulfilled, they are not what this science should be about. It is better to be honest and avoid overstatement when promoting science to the larger community.

In collaboration with my students, I am developing an educational project on ethnobotany that may help clarify the diversity of approaches to ethnobotanical research. We plan to produce a hybrid CD-ROM–Internet information system that can be used by anyone interested in learning about the different areas of research in ethnobotany, the importance of traditional knowledge, and the need to evaluate that knowledge scientifically. Given the scarcity of science libraries in developing countries, availability of the full texts of articles could be a great help for students and teachers of any course on human–plant relationships. We are including texts (from journals and books), videos, slide–tape shows, interviews, and hundreds of illustrations.

As part of this project, I selected and scanned many articles from the finest journals in the field, to be incorporated into the CD-ROM. It was an unpleasant surprise to discover the outrageous fees that most journals charge for the rights to use articles in a CD-ROM. (In contrast, a few journals, such as Science, have a generous attitude and have given us free use of their articles.) If I have to pay $3 for each article (even for articles of my own!), the cost of the disk would be outrageous—more than $150 for each disk produced. Of course, I chose not to include most of the expensive articles. This is sad, because the same journals that publish those articles are very expensive and not available in developing countries’ libraries.

It seems to me that something very wrong is happening to scientific publications. They are becoming expensive and, as a result, out of reach of students and scientists from developing countries. I believe that something has to change. As scientists, we want our articles to be read, discussed, and reproduced as many times as possible. Unfortunately, current economic trends are taking us in another direction. I agree with Van de Sompel and Lagoze (2000) that “the full transfer of rights from author to publisher often acts as an impediment to the scholarly author whose main concern is the widest dissemination of results.” I would love to see the day when we can have Internet sites containing selected articles for teaching and research purposes. Instead of sending reprints, we could post articles on the Internet as an e-Print. Scientists need to consider seriously the Open Archives Initiative (www.openarchives.org/) for biodiversity publications. We need to make our work accessible to the world.

What is the connection between these projects and the problems with access to biological materials? The answer is simple. Researchers from industrialized nations need to devote some time to projects that may help build better communication and understanding with our colleagues in less-developed countries. We need to show by our actions that we really care about and understand the social, political, and economic problems involved in our research. Finally, we need to develop true collaborations with local scientists, students, and institutions interested in biodiversity research. Good international research teams could be a major factor in finding better policies and obtaining better understanding.

If scientists do work that may have direct application and potential economic gain, we should be honest and keep our partners well informed. There is nothing wrong in looking for new medicines, foods, biocides, and genes from our world’s biodiversity. On the contrary, we need good partners to help find those new chemicals that can make a difference in our quality of life. But researchers from the developed world need to behave ethically when we work in other countries. Especially, we need to pay attention to compensation, equitable sharing, active participation, full disclosure, confidentiality, and respect. We should be very honest about the information we provide to the public. We should not lie or exaggerate to help our point be accepted. We should keep doing what we know best—practicing good scientific research, educating new generations of scientists, and communicating to society the important opportunities and challenges that may affect the future of our biosphere.

Most of all, we should find ways to work with, recognize, and compensate indigenous societies—because they include the poorest of the poor, because we have a moral obligation to treat them fairly, and because our society owes them an old debt. Indigenous societies have been the guardians and builders of much of the biodiversity that we enjoy and that we now want to protect, study, and utilize. They deserve nothing less than our full support.

Acknowledgements

This article was based on two presentations, one at AIBS’s 54th annual meeting on “Bioethics in a Changing World,” 21–23 March 2003, and the other at the conference on “Genetic Resources for the New Century,” organized by the Zoological Society of San Diego, 7–11 May 2000. The manuscript benefited greatly from the suggestions of Michael F. Allen and Norman C. Ellstrand, from the professional editing of Laura Heraty, and from the helpful comments of two anonymous reviewers. Biodiversity research at El Eden Ecological Reserve has been broadly supported by the University of California–Riverside, the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States, the National Council for Science and Technology of Mexico, the National Science Foundation, and the Office of the President of the University of California.

Figure 1

Observation tower of El Eden Ecological Reserve biodiversity

Photograph: Courtesy of El Eden Ecological Reserve.

__________________________________

Arturo Gómez-Pompa (arturo.gomez-pompa@ucr.edu) is University Professor in the Department of Botany and Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521

© 2004 American Institute of Biological Sciences

Go to Original – academic.oup.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.