The CIA Has a Long History of Killing or Trying to Kill Leaders around the World

ANGLO AMERICA, 8 May 2017

US intelligence agency has since 1945 succeeded in deposing or killing a string of leaders, but was forced to cut back after a Senate investigation in the 1970s.

North Korea’s ministry of state security accused the CIA of an alleged recent assassination attempt on Kim Jong-un.

Photograph: Wong Maye-E/AP

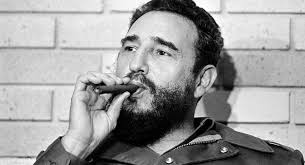

5 May 2017 – Some of the most notorious of the CIA’s operations to kill world leaders were those targeting the late Cuban president, Fidel Castro. Attempts ranged from snipers to imaginative plots worthy of spy movie fantasies, such as the famous exploding cigars and a poison-lined scuba-diving suit.

But although the CIA attempts proved fruitless in the case of Castro, the US intelligence agency has since 1945 succeeded in deposing or killing a string of leaders elsewhere around the world – either directly or, more often, using sympathetic local military, locally hired criminals or pliant dissidents.

According to North Korea’s ministry of state security, the CIA has not abandoned its old ways. In a statement on Friday, it accused that the CIA and South Korea’s intelligence service of being behind an alleged recent an assassination attempt on its leader Kim Jong-un.

The attempt, according to the ministry, involved “the use of biochemical substances including radioactive substance and nano poisonous substance” and the advantage of this was it “does not require access to the target (as) their lethal results will appear after six or 12 months”.

The person directly responsible was allegedly a North Korean working for the foreign intelligence agencies.

A CIA spokesman refused to comment on the allegations.

But although such a claim cannot be dismissed as totally outlandish – given the long list of US involvement in coups and assassinations worldwide – the agency was forced to cut back on such killings after a US Senate investigation in the 1970s exposed the scale of its operations.

Following the investigation, then president Gerald Ford signed in 1976 an executive order stating: “No employee of the United States government shall engage in, or conspire in, political assassination.”

The executive order was partly out of embarrassment at the role of the CIA being publicly exposed – but also an acceptance by the federal government that US-inspired coups and assassinations often turned out to be counterproductive.

In spite of this, the US never totally abandoned the strategy, simply changing the terminology from assassination to targeted killings, from aerial bombing of presidents to drone attacks on alleged terrorist leaders. Aerial bomb attempts on leaders included Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi in 1986, Serbia’s Slobodan Milosevic in 1999 and Iraqi president Saddam Hussein in 2003.

Earlier well-documented episodes include Congo’s first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba of Congo, judged by the US to be too close to close to Russia. In 1960, the CIA sent a scientist to kill him with a lethal virus, though this became unnecessary when he was removed from office in 1960 by other means. Other leaders targeted for assassination in the 1960s included the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, president Sukarno of Indonesia and president Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam.

In 1973, the CIA helped organise the overthrow of Chile’s president, Salvador Allende, deemed to be too left wing: he died on the day of the coup.

The alleged North Korean plot sounds crude. But intelligence agencies still resort to crude methods. The alleged North Korean plot recalls the assassination of the Russian dissident Alexander Litvinenko in 2006. A British inquest concluded he had been killed by the Russian intelligence agency using polonium hidden in a teapot.

The US has developed much more sophisticated methods than polonium in a tea pot, especially in the fields of electronic and cyber warfare. A leaked document obtained by WikiLeaks and released earlier this year showed the CIA in October 2014 looking at hacking into car control systems. That ability could potentially allow an agent to stage a car crash.

Recent failed North Korean missile attempts – as well as major setbacks in Iran’s nuclear programme – have been blamed on direct or indirect planting of viruses in their computer systems.

It is a long way from the crude, albeit imaginative and eventually doomed, methods employed against Castro. The US admitted to eight assassination attempts on Castro, though the Cuban put the figure much higher, with one estimate in the hundreds. Castro said: “If surviving assassinations were an Olympic event, I would win the gold medal.”

________________________________________

Ewen MacAskill is the Guardian’s defence and intelligence correspondent. He was Washington DC bureau chief from 2007-2013, diplomatic editor from 1999-2006, chief political correspondent from 1996-99 and political editor of the Scotsman from 1990-96.

Go to Original – theguardian.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.