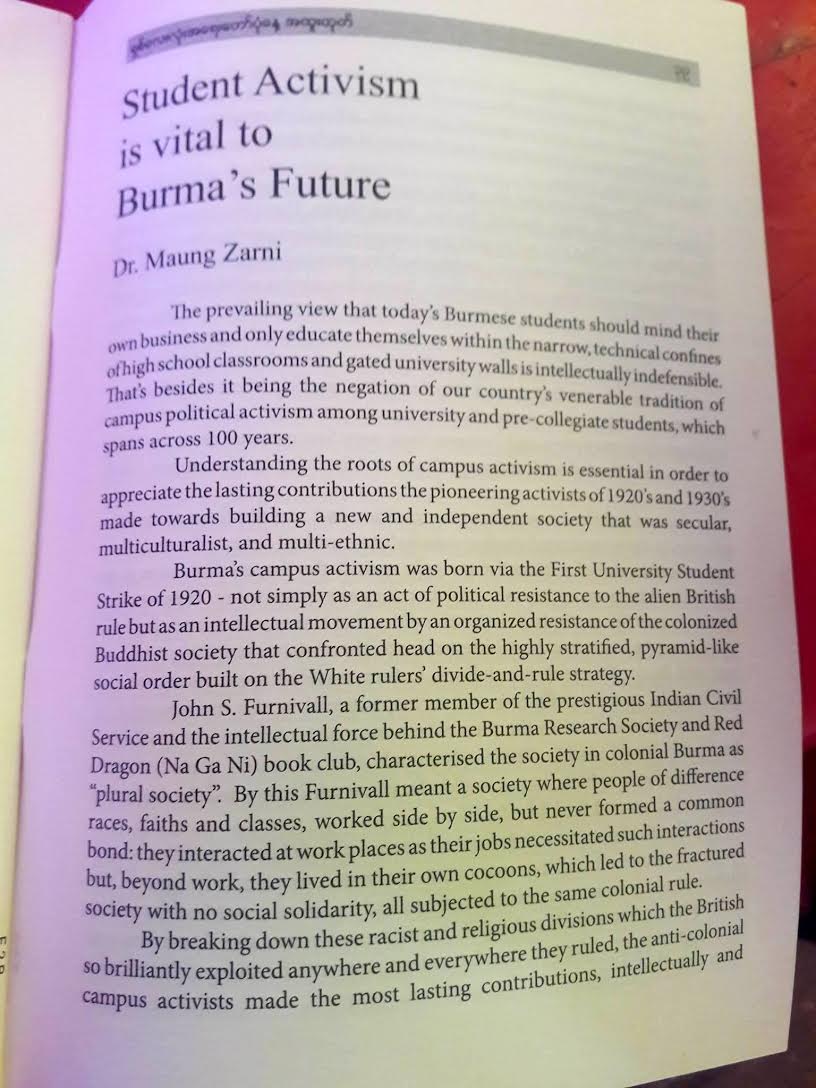

Student Activism Is Vital to Burma’s Future

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 14 Aug 2017

Maung Zarni – TRANSCEND Media Service

The prevailing view that today’s Burmese students should mind their own business and only educate themselves within the narrow, technical confines of high school classrooms and gated university walls is intellectually indefensible. That’s besides it being the negation of our country’s venerable tradition of campus political activism among university and pre-collegiate students, which spans across 100 years.

Understanding the roots of campus activism is essential in order to appreciate the lasting contributions the pioneering activists of 1920’s and 1930’s made towards building a new and independent society that was secular, multiculturalist, and multi-ethnic.

Burma’s campus activism was born via the First University Student Strike of 1920 – not simply as an act of political resistance to the alien British rule but as an intellectual movement by an organized resistance of the colonized Buddhist society that confronted head on the highly stratified, pyramid-like social order built on the White rulers’ divide-and-rule strategy.

John S. Furnivall, a former member of the prestigious Indian Civil Service and the intellectual force behind the Burma Research Society and Red Dragon (Na Ga Ni) book club, characterised the society in colonial Burma as “plural society”. By this Furnivall meant a society where people of difference races, faiths and classes, worked side by side, but never formed a common bond: they interacted at work places as their jobs necessitated such interactions but, beyond work, they lived in their own cocoons, which led to the fractured society with no social solidarity, all subjected to the same colonial rule.

By breaking down these racist and religious divisions which the British so brilliantly exploited anywhere and everywhere they ruled, the anti-colonial campus activists made the most lasting contributions, intellectually and ideologically speaking.

The political contributions of colonial-era campus activism are well-documented – and well recognized nationally. After all, Burma’s National Day is the celebration of the very first anti-colonial student strike – known as the First University Strike.

Often scholars and the public mention names such as Thakhin Mya, Aung San, Nu, Ba Hein, Rashid, Ba Swe, Kyaw Nyein, Thein Pe (Myint), Oway Nyo Mya, Bo Let Yar, etc. as the gifts that campus activism gave to the colonized society, who rose to prominence and formed the post-independence leadership (save the martyred Mya and Aung San). It was the campus activist leaders and the rank and file – such as Thakhin Ba Thaung, Tun Sein, Ba Sein, etc. who went on to found the most inspiring secularist anti-colonial organization, We the Burmese Federation, in the preceding years before the World War II. It was also a former student activist “Ko Aung San” and his Marxist-influenced student comrades, who, under Fascist Japan’s patronage, gave their fellow subjugated country-men and -women their very first national army in 1942, the first since the fall of Konbaung Court at Mandalay in November 1885.

But to limit the assessment of the tradition and contributions of campus activism to these venerated student nationalists – now all deceased – and their inspirational tales of nationalist struggle against the imperialist ruler is to overlook perhaps a very crucial foundation they attempted to lay. They worked hard to create the exemplary national politics that transcended, and that was to continue to transcend post-independence, the divisive and toxic issues of race and faith. This inclusive politics, in turn, enabled these young radical intellectuals, to be so effective and so inspirational as the main source of progressive social force in the then otherwise reactionary and/or tradition-shackled colonial world. One needs to only take a cursory glance at their revolutionary pamphlets, essays, and declarations which rejected the discourse of “feudal kings and Buddhist faith”.

The strategic and intellectual relevance of their kind of politics – both secular & multiculturalist – cannot be overstated, particularly against the backdrop of our country’s institutionalized and legalized anti-Muslim racism, both within the nominally ruling NLD and the real power, the Tatmadaw, and to a lesser degree, religious discrimination against Christians, Hindus and other non-Buddhists.

In complete and utter violation of the founding vision of Aung San and his fellow leaders, many of whom cut their teeth in the anti-imperialist campus activism, the Tatmadaw has pursued an unwritten policy of cleansing itself of all non-Buddhist officers, particularly those with Islamic and Christian backgrounds. As if not to be outdone, Aung San’s daughter made the decision to not have a single Muslim representative in her NLD, thereby creating a situation where the country’s legislature is almost exclusively Buddhist. Today, we have a deeply non-secular country where national identity is based nearly exclusively on Buddhism. The unhealthy saying “to be Burmese is to be Buddhist” has become both a popular and official reality – to the detriment and alienation of all non-Buddhist communities and non-ethnically Bama or Bama-identified communities for whom Burma is their only home.

That is like setting back the ideological and intellectual clock of the country back to the colonial days of “divide and rule”.

Contrast this extremely regressive politics, pursued officially and popularly in today’s Burma, with that of the campus activists nearly 100 years ago. As many know, the First University Student Strike challenged the British authorities on the University Act, which restricted access to higher education for the colonial public and set stringent rules and control over a small body of university students privileged enough to be able to afford university education. What is lesser known is that the resulting National Education Movement which established “national schools” were very liberal by today’s standards in Burma. While they provided the compulsory religious education for the Buddhist students who felt their faith had been trampled on by British colonial policies and in the realm of curriculum they allowed other non-Buddhist faiths to organize curricula and instructions for those of their own faiths, if there were enough non-Buddhist students.

In the subsequent birth of the student union, made up of campus activists from Christian-dominated Judson College and University College, as well as Indian (Muslims and Hindus), Chinese, Buddhist of various ethnic backgrounds, and “mixed race” students joined hands together forging a multi-ethnic, multiculturalist and democratic model of politics, unprecedented in Burma’s recorded history, pre- and post-colonial. Today’s anti-Muslim Burmese public may be surprised to learn that it was a Muslim student of Indian ancestral origin named Tun Sein who successfully challenged and persuaded his Buddhist and other student activists at Rangoon University to stop singing Britain’s “God save the King” at every Student Union meeting.

As a matter of fact, that same Muslim student – Tun Sein – went on to become the Second President of Rangoon University Student Union and subsequently co-found We the Burmese Federation, with the first Thakhin – Thakhin Ba Thaung, a university tutor and nationally acclaimed writer. With the staunch campaigning by prominent Buddhist nationalist students such as Ba Sein (later Thakhin Ba Sein), the Muslim activist could beat a Buddhist candidate named Maung Ein for the Student Union’s top leadership position.

There were other non-Buddhist names who rose to national prominence as a result of their campus activism. Rashid, Razak, and Pe Khin spring to mind. Pe Khin, a Muslim student from upcountry Burma, beat Aung San, a Buddhist, for an officer’s seat at Social Welfare and Reading Club at Pegu Hall, Rangoon University. They played vital roles in the successive national efforts, of which Aung San became the unrivalled leader. Aung San personally recruited Rashid and Pe Khin to be his top colleagues to secure Indian nationalists’ support and the collaboration of the Frontier Area communities at Pang Long. It was Pe Khin as head of the Frontier Areas Department within the flagship Burmese political party, the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), who helped secure Burma’s founding treaty – Pang Long Agreement – in February 1947. Likewise, Abdul Razak, for example, who was an important leader of the above-mentioned National Education movement, enjoyed overwhelming support from the Buddhist monks in tradition-bound Mandalay – his hometown.

There were also intellectual contributions made by former student activists of Sino-Burmese mixed ancestry. The late Thakhin Aung Gyi (Paung Tae) – better known as Brigadier General Aung Gyi, deputy Chief of Staff of the Tatmadaw – springs to mind. His writings in connection with the post-independence problems confronting Rakhine State, showed a very progressive and social scientific understanding of identities of the borderlands peoples such as Wa, Shans, Mons, Kachins, Karens and Rohingyas, as fluid and non-blood-based.

These national leaders were of mixed racial heritage or non-Buddhists; but evidently they were no less Burmese or patriotic than Aung San, Nu, Ba Hein, Thein Pe Myint, Soe or Than Tun.

Besides his exposure to secularist, non-racist Marxian ideas, it was Aung San’s first-hand experience working with an ethnically and religiously diverse group of talented, anti-colonial peers – such as Raschid, Pe Khin, and Razak – that enabled him in his final two years (1946-1947) as the Chair of AFPFL to define and espouse such progressive post-racial and non-racist definition of “Tai Yin Tha”, as anyone who was born in Burma, loved their birthplace and dedicated to the advancement of the country and its peoples, irrespective of faith, race, ethnicity and gender. Today’s official and popular racist talks of “protecting Buddhist faith and race” is an act of betrayal of the pre-independence dream of Burma as a secularist, multiculturalist society.

Finally, no discussion of campus activism will be complete without mentioning the movement’s contributions to gender equality. While no woman activist presided over the student union since its founding in the 1930’s, there was no shortages of woman activists who earned the nation’s highest esteem. These included the late Ahma of Ludu Press and university lecturer Ma Ohn, to name only a few. Their male counterparts recognized the important intellectual and political roles of these women activists. University Student Union election campaigns involved many female students who later distinguished themselves as nationalist leaders, beyond the confines of campus activism.

The campus activism which rose 100 years ago set a fine and viable model of national politics where individuals from a very rich mix of religious, ethnic and racial backgrounds embrace Burma as their home and make dedicated efforts for the advancement of all people. It was this kind of campus activism that gifted the colonial nation the likes of Aung San, Razak, Rashid, Ba Hein, Mya, Nu, Letyar, Ahma, Ma Ohn and others.

To tell today’s student activists to simply mind their own business and focus on educating themselves in the enclosed walls of campuses not only violates the spirit and broad mission of education – as defined by Aung San himself – but deprives the public the chance to see how Burmese can be multicultural and secular citizens. Burmese students, particularly those affiliated with the All Burma Federation of Student Unions (ABFSU), have kept alive the flame of a secularist, inclusive national vision for all. It is imperative that society at large, particularly the intelligentsia among the “grown-ups”, wake up to the value of campus activism.

All governments and political parties are corruptible as they pursue power and control for their own sake. Our Burmese campus activists, in contrast, continue to be driven by conscience, compassion and idealism, neither swayed by the corrupting influences of NGO money nor intimidated by iconic national politicians. Therefore, We, the Burmese people, must lend our hands of solidarity as campus activists attempt to take the front-line trenches for liberty, equality and universal human rights for all. Yes, fifty years of military and hybrid-military administrations have bloodied the idealistic heads of campus activists. But their heads remain unbowed.

In the Burmese society today so violently fractured by the regressive politics of racism, bigotry and exclusion it is these idealistic and principled students who are best positioned to serve as the moral compass. Their activism needs to be cherished and nurtured – not trampled on and repressed.

___________________________________________

Dr. Maung Zarni is a Burmese activist blogger, Associate Fellow at the University of Malaya, a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development and Environment, founder and director of the Free Burma Coalition (1995-2004), a visiting fellow (2011-13) at the Civil Society and Human Security Research Unit, London School of Economics, and a nonresident scholar with the Sleuk Rith Institute in Cambodia. His forthcoming book on Burma will be published by Yale University Press. He was educated in the US where he lived and worked for 17 years.

Dr. Maung Zarni is a Burmese activist blogger, Associate Fellow at the University of Malaya, a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace, Development and Environment, founder and director of the Free Burma Coalition (1995-2004), a visiting fellow (2011-13) at the Civil Society and Human Security Research Unit, London School of Economics, and a nonresident scholar with the Sleuk Rith Institute in Cambodia. His forthcoming book on Burma will be published by Yale University Press. He was educated in the US where he lived and worked for 17 years.

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 14 Aug 2017.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Student Activism Is Vital to Burma’s Future, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.