Telling the Truth about World War I

MILITARISM, 6 Nov 2017

James MacLean – TRANSCEND Media Service

Armistice Day is commemorated every year on 11 November to mark the armistice signed between the Allies of World War I and Germany at Compiègne, France, for the cessation of hostilities on the Western Front . (Wikipedia)

“It is the responsibility of intellectuals to speak the truth and to expose lies.”

— Noam Chomsky

Europe’s most prominent contemporary philosopher, Alain Badiou, has succinctly summarized the truth about what the First World War brought the world: “millions of people killed for nothing” (1).

The first guiding principle for anyone talking about the tragedy of World War I should be: Let us tell the truth.

Tocqueville’s observation that simple falsehoods hold more sway than complex truths (2) is, to be sure, an apposite characterization of the way in which monarchs, politicians, armies, schools and other avatars of the state have typically portrayed the massacres of the First World War, for which their counterparts of the time bore responsibility. The cliché, misattributed to Aeschylus but circulating at the time of the First World War, that “the first casualty in war is the truth”, is certainly correct.

The politicians who were organizing the slaughter in the trenches knew that they had to lie. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George confided to the editor of the Guardian, C.P. Scott, on December 27th, 1917, “If people really knew, the war would be stopped tomorrow. But of course they don’t know, and can’t know” (3).

Belgium: Destruction In World War-I 1914-1918. The Cloth Hall at Ypres again the center of interest. Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

Our soldiers did not sacrifice themselves so we could be free

An often-heard distortion of the truth concerning World War I is found in the use of the word “sacrifice” to describe the death and injuries of those who went to another continent to kill strangers in a political context of which they had little understanding, except that they were killing and dying “for King and Empire”.

The term “sacrifice” is borrowed from the world of religion, where it refers to a human being or an animal being killed in order to obtain some benefit from God or the gods. In order for a death to be a sacrifice, it cannot simply be the result of deliberate killing. The victim(s) must be killed on behalf of some person or group of people to whom a benefit is assumed to accrue as a result. But the killing of young Newfoundlanders and Canadians sent to the trenches of France brought only suffering and heartbreak to their friends and families, to whom absolutely no benefit whatsoever accrued.

The most absurdly counterfactual claim about World War I occasionally heard, especially in mid-November, is that the young men who were beckoned to leave their outport families and their fishing boats in Newfoundland, or their farms and factories in Canada, to cross the sea to another continent, and there to take up rifles and shoot strangers, young men who themselves were frequently wounded or killed during the battles, took part in this carnage “so that we might be free.”

This lie is repeated shamelessly by so-called mainstream media. For example, on November 11, 2012, the top CBC news report of the day described in its opening sentence the November 11 commemoration as “a tribute to the men and women who fought for and in many cases died for the freedoms cherished by all.”

The irony of this absurd claim is that nothing is more antithetical to human freedom than the life of the soldier at war. The soldier totally abandons his (and sometimes her) freedom to his officers and especially to his politicians. Above all he abandons his faculty of moral judgement, and therewith his humanity, transforming himself from a human into a mindless killer. When ordered to do so, he lies, he steals and he kills without a thought. When he is told to obliterate a whole city with all its unarmed children, women and men, he does. He gives up not only his freedom, but his very ability to think. He must, literally, become stupid. He may not ask himself, “Do facts and reason prove that I should slaughter these hundreds of thousands of people?” He is ordered to do so; he does so.

Once entrenched in public consciousness, the lie about the purpose of the First World War has made all the easier retroactive, counterfactual justifications for the Second World War (that our soldiers fought to defend European Jews against persecution, that Hitler wanted to conquer the world, etc.) and for other wars like the invasion of Afghanistan and the bombing of Libya.

The Great War was not great

Suppression or distortion of the truth can be subtle, and often occurs in the seemingly innocent choice of terms used to depict a particular reality. An example of such distortion is the expression the Great War. The fact that the horrific killing of the First World War was carried out on a theretofore unprecedented scale gave rise at the time to the term “The Great War”. But apart from a few rare or fossilized expressions, the word “great” is today rarely used in its older sense of “large”. The common meaning of the word “great” has shifted over the last century, and the most frequent sense of “great” in contemporary Canadian English is “good, enjoyable, excellent, of the highest quality”.

Use today of the obsolete expression the Great War constitutes a double distortion of the truth. First, in the older sense of “large”, the amount of killing in the Second World War was even greater than the amount of killing in what had once been the Great War. Secondly, with respect to the common meaning today of the adjective “great”, there was absolutely nothing good or enjoyable or excellent about the daily slaughters in the trenches of Lorraine and Flanders.

Death, chaos and ugliness cannot be life, order and beauty

Distortion of the truth does not occur only in the verbal recounting of history. The truth can be perverted also in gestures, art, music, prayers, clothing, and in a wide range of cultural practices from royal weddings to the conferral of honorary university degrees, in which the abominable filth and blood of war are prettified and sublimated in a complete inversion of reality, where death, chaos and ugliness are fancifully transformed into life, order and beauty with music, poetry, choreographed movement and the display of red tunics, brass buttons, shining medals and brightly polished boots.

Professional killers should not be honoured qua professional killers

I use the term “professional killers” here to designate those whose vocation was candidly described by General Rick Hillier: “Our job is to be able to kill people” (4).

“Why are you killing me?”, asked the seventeenth-century scientist and Christian philosopher Blaise Pascal in his Pensées.

“Well, do you not live on the other side of the water? If you lived on this side, my friend, I would be a murderer. But since you live on the other side, I am a hero, and it is just.”

“Can anything be more ridiculous,” continued Pascal, “than that a man should have the right to kill me because he lives on the other side of the water, and because his ruler has a quarrel with mine, though I have none with him?” (5)

Only God knows whether those who slaughtered their fellow human beings on the other side of the ocean, because some foreign and local politicians asked them to, are personally culpable of murder, or whether they were blinded by “invincible ignorance” (to borrow a term from theology). Voltaire was inclined to consider that soldiers from different nations who slaughter one another are unfortunate “madmen” to be pitied (6), and that those who bear responsibility for the killing are rather the politicians and generals, “those sedentary barbarians who from within their offices order, while they are digesting their meal, the massacre of a million men” (7).

A different perspective holds that “existence precedes essence”, i.e., that an individual’s “essence” is not foreordained but is determined by those decisions which an individual consciously makes herself or himself, that, in other words, a person is “the sum of their acts”, and is herself or himself responsible for their actions. They cannot, from this point of view, plead their innocence for killing and other crimes they have committed because of their ignorance or their susceptibility to mass hysteria. Tolstoy in essays like The Slavery of Our Times regularly calls the work of soldiers “murder”, just as earlier Percy Bysshe Shelley had had no qualms about using this concept to characterize the killing of other humans by a soldier: “It is no excuse that he does so in uniform: he only adds the infamy of servitude to the crime of murder” (8).

What is a commemoration good for?

As the hundredth anniversary of World War I approaches there will be commemorations of the war.

Any commemoration of a tragedy is useful only if by bringing to mind the suffering of its victims and their families it motivates public consciousness to do whatever is necessary to prevent the repetition of such a tragedy.

A commemoration of the tragedy of September 11th, 2001, which emphasized the courage and devotion of the suicide terrorists, or which explicitly or implicitly intimated that it is acceptable to fly passenger airplanes into office towers, because of American influence and invasions in the Muslim world, would be grotesque. A commemoration of the tragedy of September 1914-November 1918 which explicitly or implicitly intimates that it was acceptable to send young men from Newfoundland and Canada across an ocean to shoot strangers and to be shot by them, because of a system of political alliances in Europe, would be no less grotesque.

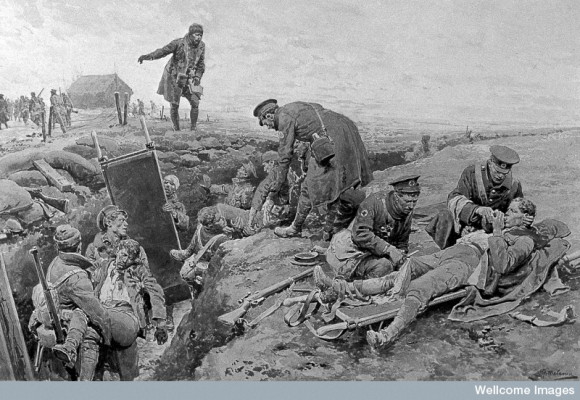

WWI Grey and brown wash drawing: work of the Royal Army Medical Corps; first aid. Drawing by Fortunio Matania. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons.

Commemorations do not occur in a vacuum, but under specific historical, social, economic and ideological conditions. A commemoration cannot be disconnected from these conditions, and cannot therefore be “neutral”. It will either reinforce or confront these various conditions. Among such conditions in today’s political and economic order is what certain sociologists (e.g., Philippe Zarifan) and philosophers (e.g., Antonio Negri) call “the regime of permanent war”. As the state increasingly abandons its regulatory and protective functions in the economy, it surrenders power to private corporations, engendering a new order where, as social philosopher Alain Joxe aptly puts it, “corporations have sovereignty and states have interests”. Economic activity becomes progressively attached to war, while the role of the state increasingly consists of creating a market for the war industry by organizing expeditionary invasions, occupations and robotic bombing of poor, traditionalist and typically tribal societies with very weak central state structures. In this context, the commemoration of past wars, if they are characterized in this commemoration as being “normal” or even good, will serve to reinforce the regime of permanent war. Universities are often conscripted into the contemporary war economy when they accept partnerships with weapons manufacturers, agree to train military personnel, and adopt symbolic practices that serve to legitimize and sublimate the horrors of expeditionary wars.

Such reinforcement is however precisely the opposite of what is needed in today’s interdependent world, and more specifically in Canada and in Newfoundland and Labrador. Young people in our province and country deserve to be able to look forward to a future where they and their families can live in a country that is at peace.

If, as suggested above, the soldiers of the First World War cannot be “honoured” on account of their homicidal-suicidal behaviour, there is nevertheless a manner in which the memory of their deaths can be honoured. That manner is to do everything possible to spare present and future generations the fate of those who died in the First World War. Indeed, it could be said that doing otherwise is to dishonour their deaths. Concretely this would mean some substantial changes in the policies of the university, especially with respect to the training of military personnel and to contracts with the war industry.

Was World War I normal?

The language and tone of many modern official and journalistic references to World War I imply that its hideous massacres were just a normal part of human history and human destiny. This perception of the war, and of all others, has, to be sure. a very long history, with deep roots in myth, ritual, literature, politics, education and religion. Exactly the same thing could have been said three centuries ago of slavery, torture, public executions, and the disenfranchisement of women. The notion of the normalcy of war is thus a fundamentally defeatist notion, and it should be combated with the same vigour that over the last three centuries the normalcy of age-old practices like slavery, torture, public executions, and the disenfranchisement of women have been combated and discredited.

Why did they do it?

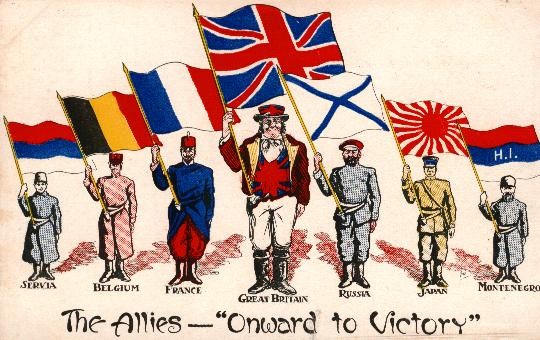

Let us recall briefly the events which resulted in Newfoundlanders and Canadians going to France to kill Germans and to be killed by them. In June 1914 the Archduke of Austria was assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in the Austrian territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Through a network of alliances, it transpired that Newfoundland and Canada found themselves on the side of the Serbs, and was therefore asked to send its young male citizens to France in order kill Germans and possibly be killed by them. This is because Newfoundland and Canada, as dominions in the British Empire, were allied to Britain. Britain in turn was allied to France. France was allied to Russia, and would not give guarantees to Germany — which is for her part was allied to Austria — that it would not support Russia, which had mobilized its army because it in turn was allied to Serbia, which was threatened by Austria, with the result that Germany had attacked France through Belgium. Therefore when Britain declared war on Germany, Newfoundland and Canada, being part of the British Empire, were at war with Germany.

Why would any young Newfoundlander or Canadian voluntarily take part in such an absurd scenario? This is a question which qualified scholars might try to answer as part of a research project in the context of the commemoration of the war. But the very absurdity of scenario points to the extreme complexity of the question, which is certainly beyond the compass of any single academic discipline. Part of the answer is obvious in the scenario itself, namely the alliance system which has seen young Newfoundlanders sent off for more than a century, from the Boer War (as individual volunteers) to the 2011 bombing of Libya, to wars half way around the world that had absolutely nothing to do with their life in Newfoundland. What are the mechanics of alliance systems that lead to bloody confrontations which cannot be explained in terms of the interests of many of their protagonists?

Another aspect of the question belongs properly to the domain of social psychology. What kind of social organization interacting with what kind of individual personalities makes it possible for societies such those of Newfoundland and Canada in 1914 to be whipped up into a frenzy of hatred against another people, and to send their youth across an ocean to kill strangers? Any answer to this question must presumably make reference to notions of mass hysteria, but the answer must also be complex, multidimensional and interdisciplinary.

NOTES:

- “Des millions de morts pour rien.” L’Explication (2010), p.52. Cf. p. 27: “…une boucherie aussi dépourvue de tout sens et atroce que celle de 14-18” (… a butchery as atrocious and devoid of any sense as the First World War).

- “Il n’y a, en général, que les conceptions simples qui s’emparent de l’esprit du peuple. Une idée fausse, mais claire et précise, aura toujours plus de puissance dans le monde qu’une idée vraie, mais complexe.” De la démocratie en Amérique (1835), tome 1, p. 267.

- Diary entry of C.P. Scott, published in “British Journalism and the First World War: Primary Sources”, Spartacus Educational, http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/JscottCP.htm

- The Globe and Mail, July 5, 2006.

- “Pourquoi me tuez-vous ? Eh quoi ! ne demeurez-vous pas de l’autre côté de l’eau ? Mon ami, si vous demeuriez de ce côté, je serais un assassin…; mais, puisque vous demeurez de l’autre côté, je suis un brave et cela est juste… Se peut il rien de plus plaisant qu’un homme ait droit de me tuer parce qu’il demeure au delà de l.eau et que son prince a querelle contre le mien, quoique je n’en aie aucune avec lui ?”Pensées (1670), no. 293-294.

- Micromégas (1752), chap. 7: “… à l’heure où je vous parle, il y a cent mille fous de notre espèce, couverts de chapeaux, qui tuent cent mille autres animaux couverts d’un turban, ou qui sont massacrés par eux.”

- Loc. cit. : “… [ce n’est pas eux qu’il faut punir, ce sont] ces barbares sédentaires qui du fond de leur cabinet ordonnent, dans le temps de leur digestion, le massacre d’un million d’hommes, [et qui ensuite en font remercier Dieu solennellement].”

- A Declaration of Rights (1812), XII. Emphasis added.

__________________________________________

Parts of this essay were included in an October 26, 2012 submission to the committee organizing commemorative events for World War I at Memorial University of Newfoundland.

James MacLean – Associate Professor of French (retired), Department of Modern Languages, Literatures and Cultures, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Canada.

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.